Below is the First Treaty ever written with American Native Indians.

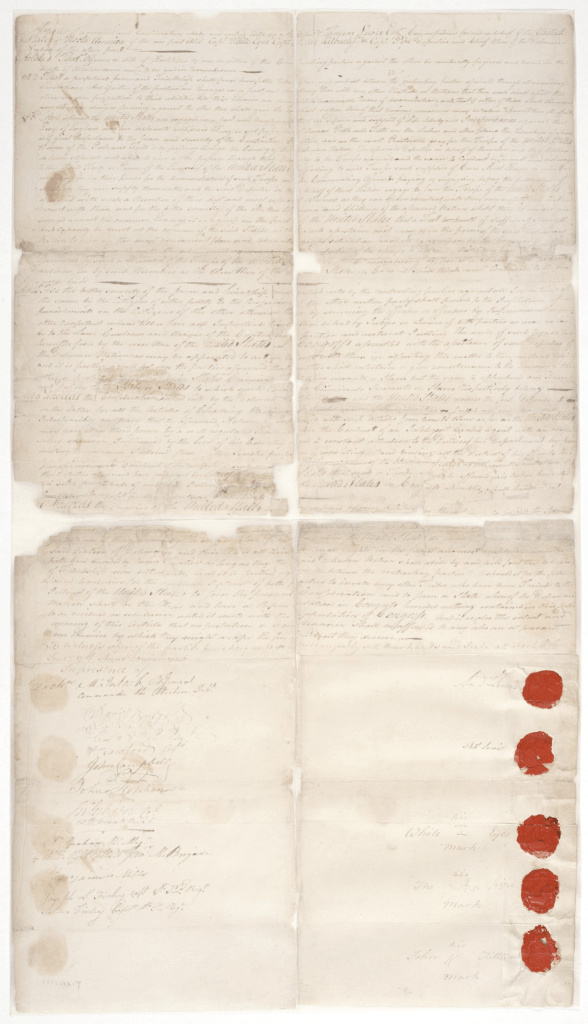

In an effort to gain support for the Patriot cause, the Continental Congress of the United States dispatched U.S. treaty commissioners to negotiate a treaty of peace, friendship and alliance with the Lenape (Delaware), whose lands were strategically located between present-day Pittsburgh and British-held Detroit. Among other things, the treaty asked that the Delawares provide safe passage for American troops across their tribal lands in exchange for the recognition of Delaware sovereignty and the option of joining other pro-American Indian nations to form a 14th state with representation in Congress. Three Lenape leaders, White Eyes, John Kill Buck Jr. (also spelled Killbuck) and Pipe, signed the treaty Sept. 17, 1778, at Fort Pitt. Eleven Americans, most of whom were military officers, witnessed the signing. Ultimately, many Delawares ended up supporting the British in the War of Independence. Yet the treaty set an important precedent for U.S.–Indian diplomacy. Henceforth, the U.S. would deal with Native Nations as it did with other sovereign nations: through written treaties.

At the Library of Congress, there’s no telling what you’ll uncover that is interesting. How about Secret Treaties with Blood Thirsty Indians?

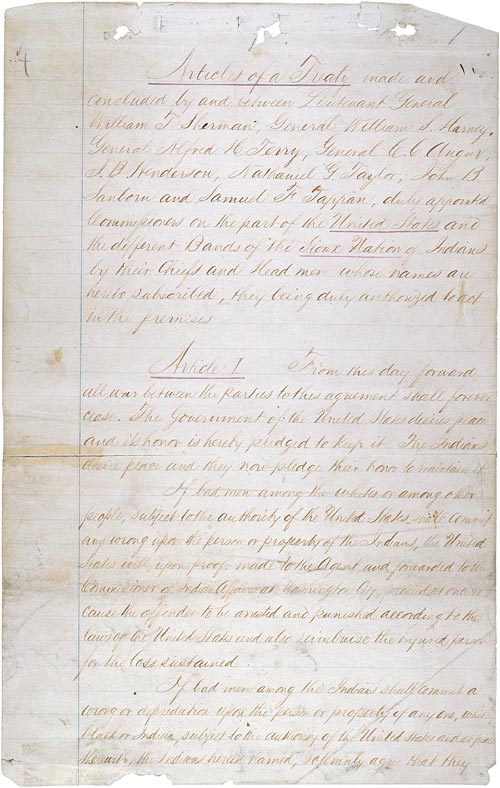

In this treaty, signed on April 29, 1868, between the U.S. Government and the Sioux Nation, the United States recognized the Black Hills as part of the Great Sioux Reservation, set aside for exclusive use by the Sioux people.

In the 19th century, the U.S. Government’s drive for expansion clashed violently with Native Americans’ resolve to preserve their lands, sovereignty, and ways of life. This struggle over land has defined the relationship between the U.S. Government and Native tribes.

From the 1860s through the 1870s, warfare and skirmishes broke out frequently on the American frontier. In 1865, a congressional committee studied the uprisings and wars in the American West. They produced a “Report on the Condition of the Indian Tribes” in 1867. This led to an act to establish an Indian Peace Commission to end the wars and prevent future conflicts.

The U.S. Government set out to establish a series of treaties with Native tribes that would force American Indians to give up their lands and move further west onto reservations. In the spring of 1868, a conference was held at Fort Laramie, in present-day Wyoming, which resulted in a treaty with the Sioux (Brule, Oglala, Miniconjou, Yanktonai, Hunkpapa, Blackfeet, Cuthead, Two Kettle, Sans Arcs, and Santee) and the Arapaho.

The goal of the treaty was to bring peace between White settlers and the tribes, who agreed to relocate to the Black Hills in the Dakota Territory. All the tribes involved gave up many thousands of acres of land that had been promised in earlier treaties, but retained hunting and fishing rights in their older territory. They also agreed not to attack railroads or settlers.

In exchange, the U.S. Government established the Great Sioux Reservation, consisting of a large portion of the western half of what is now the state of South Dakota, including the Black Hills, which are sacred to the Sioux people.

Though the reservation land was set aside for exclusive use by the Sioux people, in 1874 Gen. George A. Custer led an expedition into the Black Hills, accompanied by miners who were seeking gold. Once gold was found in the Black Hills, miners were soon moving onto the Sioux hunting grounds and demanding protection from the U.S. Army. Soon, the Army was ordered to move against wandering bands of Sioux hunting on the range in accordance with their treaty rights.

In 1876, Custer, leading an Army detachment, encountered an encampment of Sioux and Cheyenne at the Little Bighorn River. Custer’s detachment was annihilated, but the United States would continue its battle against the Sioux Tribe in the Black Hills until the government confiscated the land in 1877. To this day, ownership of the Black Hills remains the subject of a legal dispute between the U.S. Government and the Sioux Nation.

https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/fort-laramie-treaty

In 1868, Two Nations Made a Treaty, the U.S. Broke It and Plains Indian Tribes are Still Seeking Justice

The American Indian Museum puts the 150-year-old Fort Laramie Treaty on view in its “Nation to Nation” ex

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/5a/00/5a005f6c-2989-4868-a084-6e2ae55075bb/treaty.jpg)

The pages of American history are littered with broken treaties. Some of the earliest are still being contested today. The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1868 remains at the center of a land dispute that brings into question the very meaning of international agreements and who has the right to adjudicate them when they break down.

In 1868, the United States entered into the treaty with a collective of Native American bands historically known as the Sioux (Dakota, Lakota and Nakota) and Arapaho. The treaty established the Great Sioux Reservation, a large swath of lands west of the Missouri River. It also designated the Black Hills as “unceded Indian Territory” for the exclusive use of native peoples. But when gold was found in the Black Hills, the United States reneged on the agreement, redrawing the boundaries of the treaty, and confining the Sioux people—traditionally nomadic hunters—to a farming lifestyle on the reservation. It was a blatant abrogation that has been at the center of legal debate ever since.

In 1980, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the U.S. had illegally appropriated the Black Hills and awarded more than $100 million in reparations. The Sioux Nation refused the money (which is now worth over a billion dollars), stating that the land was never for sale.

“We’d like to see that land back,” says Chief John Spotted Tail.

Broken Treaties With Native American Tribes: Timeline

From 1778 to 1871, the United States signed some 368 treaties with various Indigenous people across the North American continent.

https://www.history.com/news/native-american-broken-treaties

https://www.loc.gov/item/today-in-history/june-02/

Indian Citizenship Act

On June 2, 1924, Congress enacted the Indian Citizenship Act, which granted citizenship to all Native Americans born in the U.S. The right to vote, however, was governed by state law; until 1957, some states barred Native Americans from voting. In a WPA interview from the 1930s, Henry Mitchell describes the attitude toward Native Americans in Maine, one of the last states to comply with the Indian Citizenship Act:

One of the Indians went over to Old Town once to see some official in the city hall about voting. I don’t know just what position that official had over there, but he said to the Indian, ‘We don’t want you people over here. You have your own elections over on the island, and if you want to vote, go over there.’

Just why the Indians shouldn’t vote is something I can’t understand.

You must be logged in to post a comment.