But did the Founding Fathers leave any Secret Messages for all of us to know?

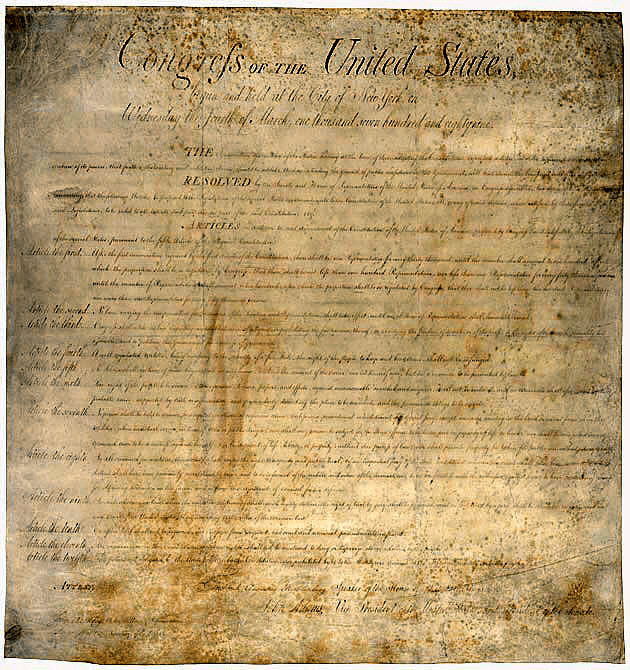

For instance, the US Constitution was recently flagged as AI-generated text! It’s important to remember that AI content detection tools are still a work-in-progress, so it’s best to use AI content detectors as a reference point in academic writing, instead of relying on them to accurately assess your work.

But did the Founding Fathers leave any Secret Messages for all of us to know? I believe that they did. But we need the CODE to decipher their Message or Messages. Where is that CODE? Which one had it? Where is it Today? In the Military, we used a two line Code. Look up on one side of a large jumbled page, then the Top. Draw a line where they intersect and BAM! You got one Letter.

Here are some resources you can explore to learn more about codes used during the American Revolution:

- National Security Agency: The National Security Agency (NSA) has a declassified document on their website that discusses American code-breaking efforts during the Revolutionary War. It mentions codebooks and cipher systems used by both American and British forces. You can find it here: American Systems in the Revolutionary War: [invalid URL removed]

DOf!:JJ?ovecA~~N NSA on 12~01-2011, Transparency Case# 63853

UNCLASSIFIED

The American Revolution’s One-Man Nutional Security Agency

There was an American who seems to have been the American Revolution’s one-man National

Security Agency, for he was the one and only cryptologic expert Congress had, and, it is claimed, he

managed to decipher nearly all, if not all, of the British code messages obtained in one way or another

by the Americans. Of course, the chief way in which enemy messages could be obtained in those days

was to capture couriers, knock them out or knock them off, and take the messages from them. This was

very rough stuff, compared to getting the material by radio intercept, as we do nowadays.

This one-man NSA was James Lovell, and besides being a self-trained cryptologist, he was also a

member of the Continental Congress. With his cipher designs, Lovell became America’s first crypto-

graphic tutor. Unfortunately, his students, the American ministers abroad, though brilliant and talent-

ed in political matters, found his systems confusing and frustrating.

James Lovell, born in 1737, studied at Harvard, taught in his father’s school in Boston, and became

a famous orator. Arrested by the British after the battle of Breed’s Hill, he was sent as a prisoner to

Halifax in 1776, but soon thereafter he was exchanged and he returned to Boston. Chosen as a delegate

to the Continental Congress, he attended the sessions of the Congress beginning in February 1777 and

served continuously until the end of January 1782 when he took his only leave. In May 1777, he was

appointed to the Committee for Foreign Affairs, where, among other responsibilities, he deciphered

dispatches. He became the Committee’s most indefatigable member, indeed, sometimes its only active

member. Other members arrived and departed, but Lovell stayed on and foi: five years never visited his

wife and children. Before he left Congress in 1782, Lovell had left his mark on American foreign rela-

tions and particularly on cryptography.

James Lovell enjoyed the challenge of making and breaking cipher systems. Unfortunately, even

learned diplomats of his time had great difficulty understanding his cipher forms completely. For John

Adams, the Lovell ciphers caused boundless confusion. As Adams confided in a letter to Francis Dana

in Paris in March 1781: “I have letters from the president and from Lovell, the last unintelligible, in

ciphers, but inexplicable by his own cipher.” In short, Adams could not read Lovell’s enciphered dis-

patches. However, John Adams was not the only diplomat troubled by Lovell’s ciphers. In February

i 780, Lovell wrote to Benjamin Franklin that the Chevalier de la Luzerne, who had become French min-

ister to the United States the previous year, was anxious because Lovell and Franklin were not corre-

sponding in cipher. Lovell had sent a cipher earlier, but Franklin ignored it. Lovell tried again. In March

1781, Franklin wrote to Francis Dana enclosing a copy of Lovell’s new cipher and a paragraph of Lovell’s

letter in which the cipher was used. Somewhat bewildered, Franklin, accustomed to a simpler cipher,

commented: “If you can find the key & decypher it, I shall be glad, having myself try’d in vain.”

Lovell’s considerable talents for breaking ciphers rewarded Nathaniel Greene and George

Washington when enciphered dispatches from the British commander, Lord Cornwallis, were inter-

cepted in 1780 and 1781. Lovell wrote to Washington that he believed the British ciphers were quite

widely used among their leaders and urged the general to have his secretary make a copy of the cipher

key that he was transmitting to Greene. Interestingly enough, Lovell had discovered a curious weakness

in the British cryptographic system: “the Enemy make only such changes in their Cypher, when they

meet with misfortunes, as makes a difference of Position only to the same Alphabet.” What Lovell

3928631

UNCLASSIFIED

meant was that the same mixed cipher alphabet was merely shifted to another juxtaposition with the

plain alphabet.

Lovell got his opportunity to break a critical British dispatch through good fortune. Sir Henry

Clinton, commander of the British forces in America, sent an enciphered dispatch via a special courier

to Cornwallis. The dispatch explained Clinton’s inability to assist Cornwallis with a fleet at Yorktown

until a specific day and urged him to hold out. Beached near Egg Harbor, the crew and courier were cap-

tured and brought to Philadelphia. It was learned that the courier had hidden the confidential dispatch

under a large stone.near the shore. Recovered, the dispatch was found to be written in three systems.

It took Lovell two days to solve and read the dispatch. The original letter was then sent on to Cornwallis

to enable the Americans to use their secret knowledge of the British plans and to counteract them.

James Lovell’s secret ciphers produced more confusion than security for American diplomats dur-

ing the revolution. Only gradually in the years after 1775 did American officials become sophisticated

about cryptographic systems. Because of the frustration with ciphers, American statesmen began to rely

more heavily upon codes rather than ciphers for secret foreign communications. All of the confusion

over the Lovell ciphers provides a remarkable lesson for cipher inventors. Lovell tried to force his sys-

tem on the best minds of the country-even they didn’t understand it, and the system failed.

[This article was adapted from Ralph Weber, Masked Dispatches: Cryptograms and Cryptology

in American History, 1775-1900, and The Friedman Legacy.; A Tribute to William and Elizebeth Friedman.)

https://www.mountvernon.org/george-washington/the-revolutionary-war/spying-and-espionage/the-culper-code-book

- George Washington’s Mount Vernon: Mount Vernon, George Washington’s home, has a webpage dedicated to the Culper Spy Ring. This ring used a codebook developed by Major Benjamin Tallmadge to send messages about British troop movements and plans. You can find it here: The Culper Code Book: [invalid URL removed]

- YouTube – Cryptology in the American Revolution: This Youtube video provides a brief overview of codes used during the Revolution, including the Culper Codebook. You can find it here: Cryptology in the American Revolution: Codes 1: [invalid URL removed]

Cryptology in the American Revolution: Ciphers 1

https://youtube.com/watch?v=k_R9KJ-j1Zs&feature=shared

These resources should give you a good starting point to learn more about the fascinating world of codes and ciphers used during the American Revolution.

- Established Codes: During the American Revolution, various codes were used for confidential communication. Some were simple substitution ciphers, where a letter is replaced by another symbol or letter. Others were more complex, like codebooks with pre-assigned meanings for words or phrases.

- Invisible Ink: Invisible ink, made from lemon juice or other weak solutions, was also a common method for hiding messages. The message would only be revealed when heated or treated with a specific chemical.

The U.S. Bill of Rights using the method you described with numbers assigned to each letter (1 for A, 2 for B, and so on).

Here’s the breakdown:

- Total Letters: There are 1,023 letters in the Bill of Rights (excluding punctuation and spaces).

- Sum of Letter Values: Adding the numerical value of each letter results in 28,352.

- Reduced Sum (Optional): Following some numerology practices, we can reduce this further by adding the digits of the sum (2 + 8 + 3 + 5 + 2) which equals 20. Then, we add the digits of 20 (2 + 0) resulting in the final number 2.

Interpretation: In some numerology systems, the number 2 is associated with cooperation, balance, diplomacy, and partnerships. It could be interpreted as reflecting the idea of the Bill of Rights creating a balanced system between individual liberty and government power.

However, it’s important to remember these are just general interpretations within a system that can be subjective. The historical context and the actual content of the Bill of Rights likely hold more meaning than the numerical value of its letters.

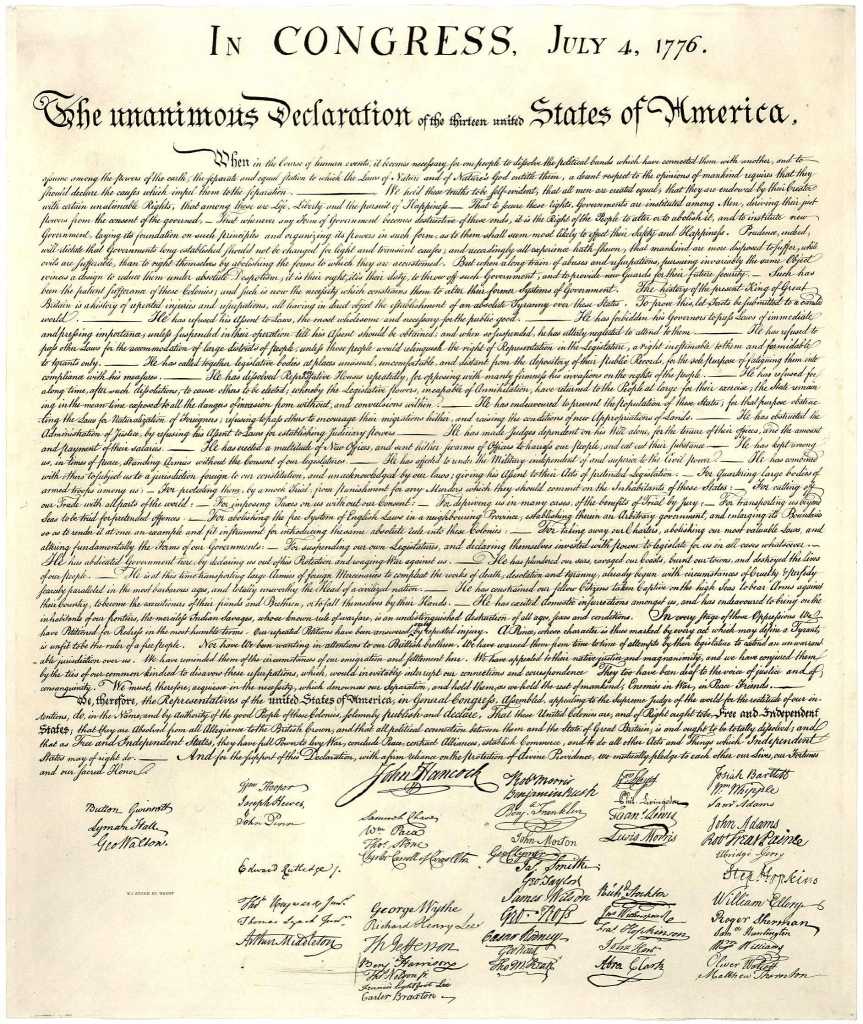

The United States Constitution using the same numerology method. Here’s the breakdown:

- Total Letters: There are 4,400 letters in the Constitution (excluding punctuation and spaces).

- Sum of Letter Values: Adding the numerical value of each letter results in 121,300.

- Reduced Sum (Optional): Following the same practice, reducing the sum further gives us 6 (1 + 2 + 1 + 3 + 0 + 0).

Interpretation: The number 6 is sometimes associated with responsibility, nurturing, harmony, and community in numerology. It could be seen as reflecting the Constitution’s focus on establishing a stable and responsible government that fosters a sense of community.

As with the Bill of Rights, these interpretations are based on a subjective system. The document itself and the historical context behind its creation provide a more reliable understanding of its meaning.

Now, regarding different approaches:

- We could explore other numerology systems with different letter value assignments.

- We could analyze the documents for specific word patterns or letter frequencies that might hold significance.

However, it’s important to remember that these methods are not based on the original intent of the documents and can be quite speculative.

You must be logged in to post a comment.