As a young man fresh out of high school in Sweetwater, Texas, I must admit I was blissfully unaware of the challenges that awaited me. My journey began with Basic Training, followed by Advanced Individual Training, and then deployment to Camp Casey in South Korea. At that time, with the Vietnam War winding down and American troops no longer being sent there, I chalked up my time served as part of my veteran status.

Let me tell you, Korea was a hardship tour. We were all so relieved to leave that we literally raised our legs high into the air as the plane took off, a collective expression of joy as we left that experience behind. We cheered and celebrated, a euphoric release marking the end of our tour—no more dealing with the complexities of life on the ground or encountering locals shouting “Kill Joe Ching,” a reference to confrontations with North Koreans.

After returning home, I attended Texas A&M and Sam Houston State University before finding myself in a situation far more daunting than anything I faced overseas. In 1978, I entered the notorious Ellis Unit, infamously known as “The Snake Pit,” where I encountered a living hell populated by angry men, many of whom were serving life sentences. The conditions were dire, and nothing in my military training could have prepared me for the chaos that unfolded inside those walls.

Knife fights were commonplace, and the atmosphere was charged with hostility. Judge William Wayne Justice III engaged with the Texas Department of Corrections through a lawsuit, exposing the inhumane conditions that inmates faced. It was brutal to witness five inmates crammed into a single cell, a sight reminiscent of a Three Stooges skit but far from comedic in reality.

The memories of the violence and the knife fights haunt me still. I vividly recall one inmate I subdued, who had been stabbed 32 times—blood spraying from his wounds like a malfunctioning sprinkler, diminishing with each heartbeat.

Although I initially vowed never to return after my first assignment, I ended up working at three more Texas prisons. Ironically, I went from the worst environments to some of the better ones. One unit was fully integrated with notorious gangs, vastly different from the Double “O” Chicano gang from Sweetwater. These gangs operated with a business mentality, raking in $50,000 to $100,000 a week through sex, drugs, food sales, and other illicit activities. Fortunately, I managed to keep my distance; I focused on my role while they respected my space, opting not to conduct business in front of me.

I retired just in time to avoid the onslaught of COVID-19, though I witnessed others I knew succumb to the virus within the prison system.

What truly frightened me, however, was the constant understaffing and being reassigned to units with even fewer guards. I faced moments of terror dealing with inmates who were mentally unstable due to drug or alcohol use, often coupled with bipolar disorder. These situations could turn violent in an instant, with blood spraying across rooms or the risk of being overpowered and slammed into the cement floor—potentially risking severe injury.

Understanding the complexities of Texas prisons is a lifelong endeavor. One thing is clear from the common saying: if you can’t do the time, don’t do the crime. However, inmates often humorously remarked, “Come to Texas on vacation and leave on probation.”

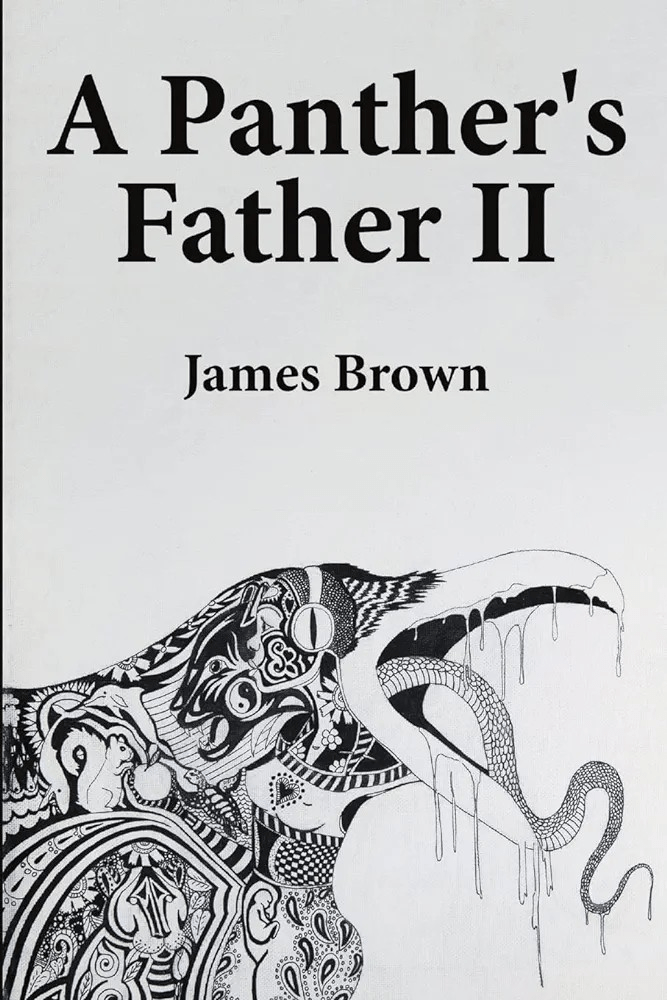

Read one of my books-.

You must be logged in to post a comment.