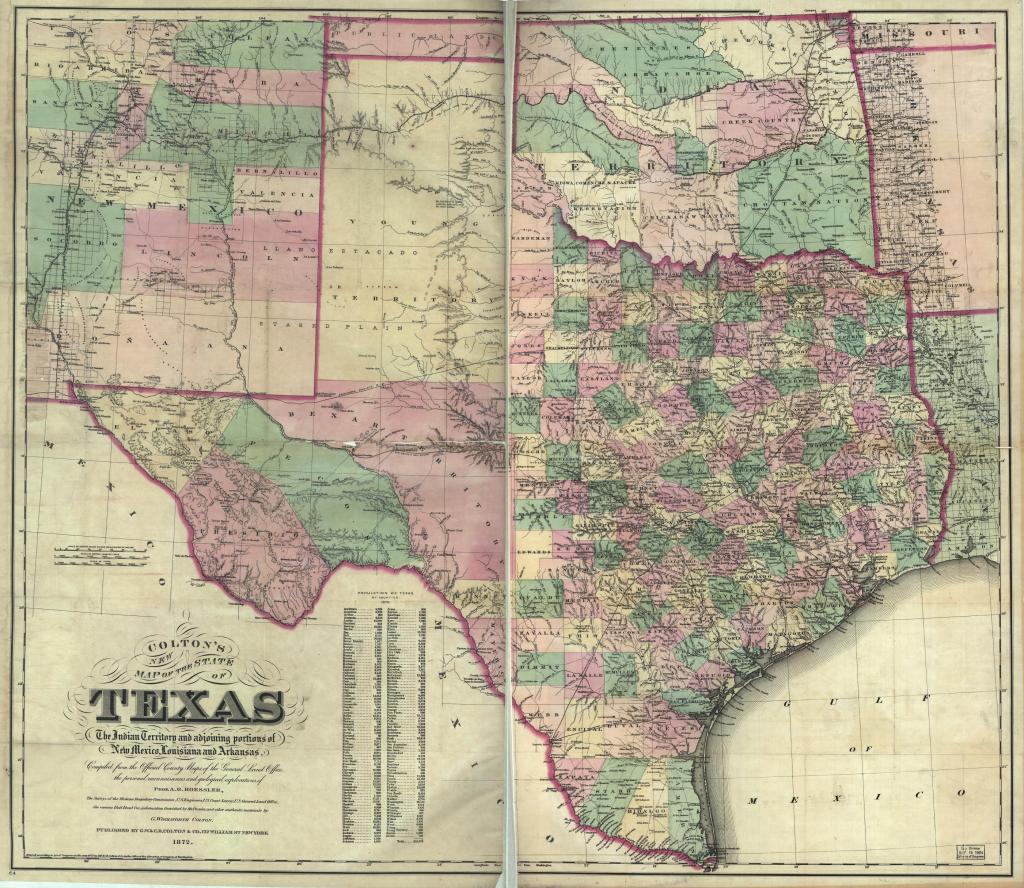

Over 20 years ago, I was studying Old Texas Maps of the 1800s. I looked at every Map I could find. And in a 10-20 year period, CAMP MARE was listed on some. It was there and then it was gone. I contacted West Point. I contacted the Library of Congress. I contacted the Texas Historical Commission.

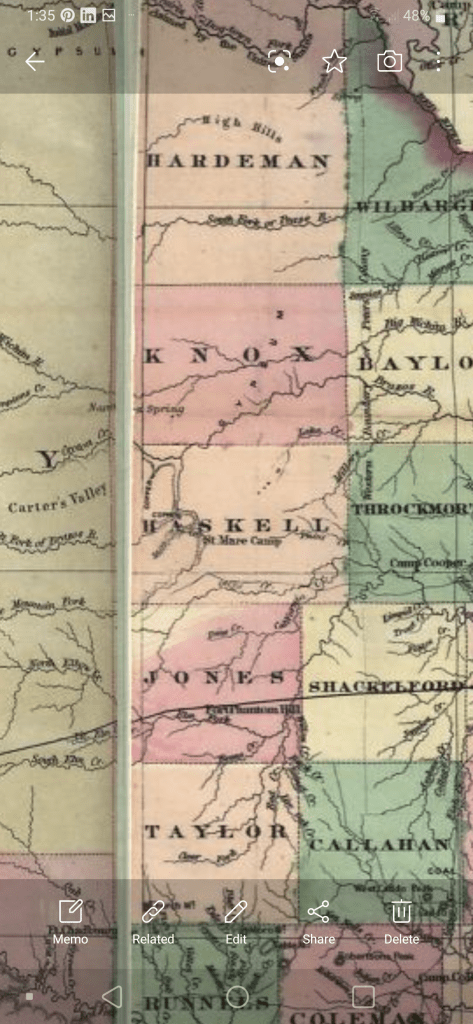

On the above 1872 Texas Map, “St. Mare Camp” in present day Haskell County, Texas. It’s “CAMP MARE” on others. Was it a Religious Camp? Who created it? Who used it? Why are there no written records about it? Somewhere, somehow, there is a record written by someone. But finding it is the great mystery. Will you solve the mystery? For over 20 years I have been searching, but found nothing. It’s on 1872 Maps of the State of Texas and all the way into 1879. But it’s gone off the Maps by 1881.

https://www.tsl.texas.gov/apps/arc/maps/maplookup/01596

Above is-

1879 State of Texas Map by N.D. Thompson & Company: This was a publishing company based in St. Louis, Missouri, active in the late 19th century, known for producing maps and other publications. Rand McNally & Co. of Chicago held the copyright for this particular map.

But no one could provide a definitive answer of What was and who Created CAMP MARE. It was there but then it disappeared…in Haskell County, Texas

GEMINI AI did a Deep Dive into “Camp Mare” today and this is what A I found-

An Investigation into “CAMP MARE” in Haskell County, Texas During the 1800s

This report addresses the query regarding the existence and nature of a place called “CAMP MARE” reportedly shown on old maps of Haskell County, Texas, during the 1800s. By examining provided historical materials, including descriptions of maps, county histories, and related information, this analysis aims to determine if such a place is documented and to provide historical context.

II. Examination of Historical Maps of Haskell County (1800s)

Several historical maps of Haskell County, Texas, from the 1800s are referenced in the provided materials, indicating a rich cartographic history for the region during this period. An 1859 map, titled “Map of Haskell County Young District,” is available, featuring geographical elements such as the Brazos River, Mulberry Creek, and other waterways. The emphasis on natural features in this early map suggests that its primary purpose was likely to delineate the landscape for exploration and potential development, rather than detailing specific settlements or camps. As the county was formally established in 1858 but remained largely unsettled until the late 1870s due to Indian hostilities , early cartographic efforts would naturally focus on the fundamental geography of the area.

By 1879, as settlement began to take hold, vintage maps of Haskell County were being produced, one of which specifically highlights notable areas like Haskell and O’Brien. This indicates a shift towards including established localities as the county developed. The mention of these specific places suggests that by this time, permanent settlements were emerging and becoming important features to document on maps for various administrative and navigational purposes.

A significant historical map from this era is an 1879 map of Haskell County created by the Texas General Land Office (GLO) and preserved by The Portal to Texas History. The GLO, established in 1837, played a crucial role in surveying and mapping Texas public lands, making their maps invaluable resources for understanding the state’s historical development. These maps often contain detailed information related to land grants, ownership, and the locations of various features within a county. The fact that this map is part of a collection of GLO Historic County Maps underscores its official nature and potential reliability for identifying place names.

Further evidence of cartographic activity includes the reference to an 1876 map of Haskell County, suggesting that multiple versions and possibly different publishers were involved in mapping the area during the 1870s. The existence of reprints of these old maps highlights their continued historical interest and the potential for them to contain unique information about the county’s past.

A map from later in the century, dated December 1899, is a survey map of Haskell County, also from the General Land Office. Survey maps are particularly important as they often provide precise details about land divisions, tracts, and any significant features noted during the surveying process. These maps could potentially include the names of camps or landmarks used by surveyors or recognized locally. Another 1899 map of Haskell County, part of the General Map Collection, was copied in May 1900, indicating ongoing efforts to document the county’s landscape and features towards the end of the 1800s. These later maps might reflect the cumulative knowledge and development of the county throughout the latter part of the century.

Interestingly, an 1879 map of Haskell County held by the Library of Congress specifically shows landownership. Maps detailing landownership are particularly relevant as they might include the names of early landowners and any associated features on their property, such as a camp. The presence of such a map in a national repository like the Library of Congress suggests its historical significance.

While not a direct map of Haskell County, an 1859 map showing the source regions of rivers in the interior of North America includes the broader geographical context of the area. Regional maps can sometimes provide clues or references to smaller localities within a specific county.

In summary, the availability of multiple historical maps of Haskell County from the 1800s, particularly those produced by the Texas General Land Office and held in significant archival collections, suggests that these resources would be the most likely place to find documentation of “CAMP MARE” if it existed and was considered a noteworthy feature at the time.

III. Historical Context of Haskell County in the 19th Century

Understanding the historical timeline of Haskell County’s formation and settlement is crucial for interpreting the potential nature and timeframe of “CAMP MARE.” Haskell County was officially formed by the Texas legislature on February 1, 1858, from lands previously assigned to Milam and Fannin counties. However, due to persistent Indian hostilities in the region, the county remained largely unsettled for nearly two decades. This period of limited settlement suggests that any “camp” established in the early to mid-1800s was more likely to be a temporary encampment associated with exploration, surveying, or military activities rather than a permanent civilian settlement.

By 1876, the perceived threat from Native American tribes had diminished sufficiently to allow for the reestablishment of the county. Ranchers began moving into the area around 1877, with key figures like George T. Reynolds and John A. Matthews establishing their ranch headquarters on California Creek. In 1879, Thomas F. Tucker, encouraged by his brother’s earlier account of the area from an 1849 expedition, settled near the Matthews ranch and started his own cattle operation. The same year, a small ranching community known as Rice Springs began to flourish near the center of the county.

The name of this central community was changed to Haskell in December 1882 in response to a request from the United States Post Office. This renaming coincided with the growing presence of settlers and the need for official postal services. Finally, Haskell County was formally organized in January 1885, with Haskell designated as the county seat. Thomas F. Tucker was elected as the first county judge, marking the official establishment of county governance.

The Swenson family also played a significant role in the county’s development, adding portions of Haskell County to their extensive SMS ranches during the 1880s. Their large-scale ranching operations would have further shaped the landscape and potentially led to the establishment of various camps or outposts across their landholdings.

The timeline of Haskell County’s history in the 1800s indicates a transition from a largely unsettled frontier in the early and mid-century to an organized county with established settlements and ranching by the late 1800s. This context suggests that if “CAMP MARE” existed, its nature would likely align with the activities prevalent during the specific period in which it was noted on maps.

IV. Potential Interpretations of “CAMP MARE”

Given the historical context, “CAMP MARE” could potentially refer to several types of locations: a military encampment, a ranching camp, an early settlement, or possibly a geographical landmark.

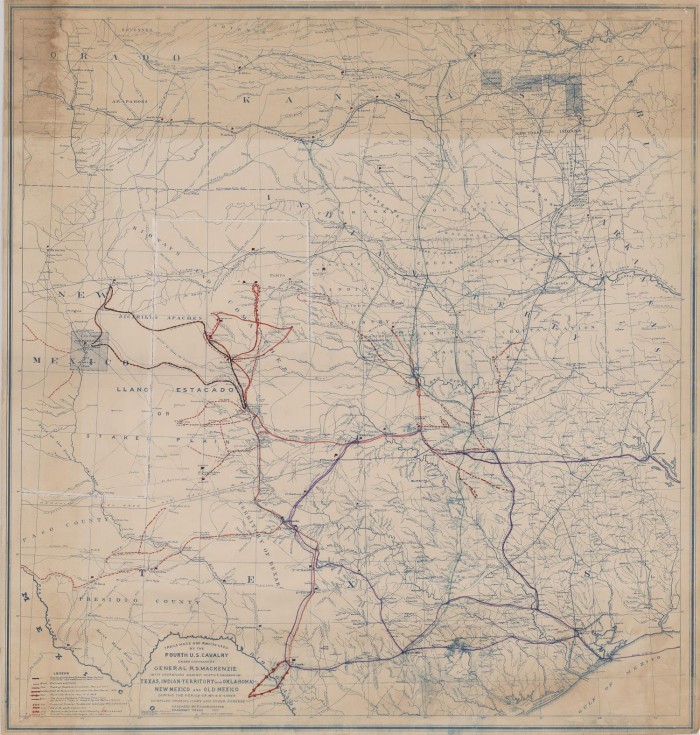

Military activities were prevalent in Texas throughout the 1800s, particularly during the period of frontier expansion and conflicts with Native American tribes. The Red River War Indian Campaign in the Texas Panhandle in 1874 and earlier engagements like the Paint Creek Fight in the present Haskell County highlight the military presence in or near the region. Surveying expeditions, often led by military officers such as Captain Randolph B. Marcy, were also common. Marcy’s 1849 expedition crossed the area along Paint Creek , and his 1854 survey aimed to locate Texas American-Indian reservations. These expeditions would have involved the establishment of temporary camps, and it is conceivable that one of these was informally or formally known as “CAMP MARE,” possibly named after a member of the expedition or due to some other association. The historical marker commemorating the Capt. R.B. Marcy Trail near Haskell further underscores the significance of military-led exploration in the area. Moreover, the existence of Fort Cooper, a military outpost in nearby Jones County, suggests a broader military context that could have extended into Haskell County.

With the rise of ranching in Haskell County starting in the late 1870s , “CAMP MARE” could have been a ranching camp. Early ranches, such as those established by Reynolds and Matthews in 1877 and Tucker in 1879 , often involved setting up temporary or semi-permanent camps for cowboys managing livestock across vast territories. The Swenson family’s SMS Ranches, which expanded into Haskell County in the 1880s , were large operations that likely utilized various camps. If a family or individual named Mare was associated with one of these early ranches, a camp might have been named in their honor.

Given that the formal settlement of Haskell County was relatively late, the term “CAMP MARE” might refer to a very early, informal community. The main settlement was initially known as Willow Pond Springs and later Rice Springs before being renamed Haskell in 1882. It is possible that “CAMP MARE” was an even earlier, unofficial designation for the same location or a nearby gathering place before these formal names were adopted.

Finally, “CAMP MARE” could potentially refer to a geographical landmark or feature. In some instances, the term “camp” might be informally added to the name of a place with specific characteristics. If a family or individual named Mare was prominent in the area, a natural feature might have been named after them, with “camp” being appended through local usage.

V. Investigation into Mentions of “MARE” or Similar Terms in Haskell County History

A review of the provided materials for any mentions of the name “Mare” or similar-sounding names associated with Haskell County in the 1800s yields limited results. A “Geno-De-Mares” is mentioned in Texas in 1939 , but this is outside the 19th century and not specifically located in Haskell County. A 2009 Haskell Free Press article refers to a “Registered Mare” , which pertains to a horse and is also outside the relevant timeframe. The name “MARSH, JERRY L.” appears in a list of unclaimed funds in Texas , but this is not from the 1800s and lacks a direct connection to Haskell County.

While these instances suggest the presence of similar names in Texas at different times, they do not directly link a “Mare” family or individual to Haskell County during the 1800s based on the provided snippets. However, this does not definitively rule out the possibility of a less prominent individual or a variation in spelling, such as “Marsh,” being associated with the area.

VI. Analysis of Surveying Expeditions and Early Land Records

Given the significant surveying activities in Haskell County during the 1800s, particularly those led by Captain Randolph B. Marcy , it is plausible that a temporary camp established by one of these expeditions could have been named “CAMP MARE.” Surveyors often recorded details about their routes, landmarks, and temporary encampments in their field notes and on their maps. These records, especially those of military surveys, might contain references to such a place.

The Texas General Land Office played a central role in surveying and mapping the state, including Haskell County. Their maps often detailed land ownership and significant features. If “CAMP MARE” was associated with a particular piece of land or was a notable landmark, it might be found on these early land records or survey maps. The 1879 GLO map held by The Portal to Texas History and the 1879 map showing landownership in the Library of Congress would be prime resources to examine for any such mention. Similarly, the 1873 and 1879 atlases of Haskell County published by the GLO might provide more comprehensive cartographic details.

VII. Conclusion

Based on the examination of the provided research materials, there is no direct and explicit mention of a “CAMP MARE” in Haskell County, Texas, during the 1800s. However, the historical context and the nature of the available resources suggest several possibilities. The late settlement of Haskell County indicates that any camp in the early to mid-1800s was likely temporary and related to exploration, surveying, or military activities. Captain Randolph B. Marcy’s significant presence in the area during this period, with his surveying expeditions in 1849 and 1854, makes it plausible that a camp associated with his activities could have been named “CAMP MARE.” Alternatively, with the rise of ranching in the late 1870s, “CAMP MARE” might have been a ranching camp, possibly linked to early ranching families. It could also have been an informal early name for a settlement before the adoption of Willow Pond Springs or Rice Springs.

The absence of a direct mention in the snippets could be due to several factors. “CAMP MARE” might have been an informal or very temporary name that was not officially recorded on major maps or in historical accounts. The spelling of “MARE” could also be a variation of another name, such as “Marsh.” Furthermore, the old maps referenced by the user might contain details not present in the provided excerpts.

To gain a more definitive understanding, further research is recommended. This should include a direct consultation of the historical maps of Haskell County from the 1800s held by the Texas General Land Office, the Library of Congress, and the Texas State Library and Archives. Examining the field notes and records of surveying expeditions, particularly those of Captain Randolph B. Marcy, could also yield valuable information. Reviewing more comprehensive local histories of Haskell County beyond the provided snippets might uncover mentions of “CAMP MARE” in narratives or less widely known records. Finally, investigating genealogical records for any families named Mare or Marsh who were early settlers or landowners in Haskell County could establish a connection to the area.

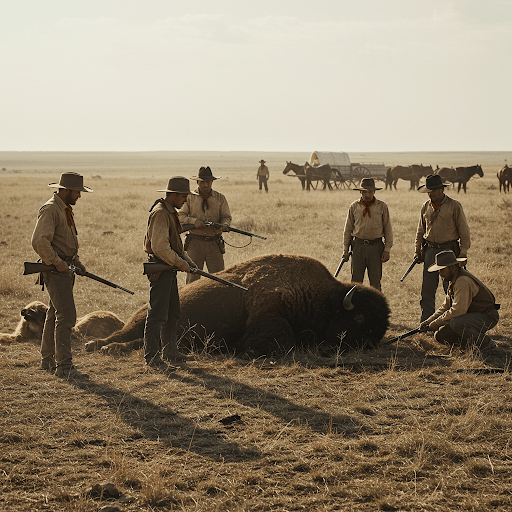

Was St. Mare Camp a Camp for Buffalo Hunters?

The history of buffalo hunting in Texas is a significant and often tragic part of the state’s past, deeply intertwined with the lives of Native American tribes, westward expansion, and the near-extinction of the American bison. This era is characterized by both immense ecological impact and profound cultural clashes.

Early Encounters and Indigenous Hunting

- Pre-Colonial Era: For thousands of years, vast herds of American bison (Bison bison) roamed the plains of Texas. These animals were central to the survival and culture of numerous Native American tribes, including the Comanche, Kiowa, and Tonkawa. The bison provided food, clothing, shelter, and materials for tools.

- Sustainable Practices: Indigenous peoples developed sophisticated hunting techniques, often involving communal surrounds, driving herds over cliffs (known as pishkuns), or using fire to direct the animals. They utilized every part of the buffalo for a multitude of purposes, demonstrating a sustainable relationship with the animal. Nothing was wasted.

- Introduction of the Horse: The arrival of horses in the 16th and 17th centuries, brought by the Spanish, revolutionized buffalo hunting for Native Americans. It allowed them to more efficiently pursue and kill buffalo, and to follow the migrating herds over greater distances. Tribes like the Comanche became highly skilled equestrian hunters.

The Era of Commercial Hunting

- Mid-19th Century: As westward expansion gained momentum and the industrial revolution increased the demand for buffalo hides (used for machinery belts, among other things) and robes, commercial hunting began to take hold in Texas.

- Fort Griffin’s Role:

- Established in 1867, Fort Griffin, located on the Clear Fork of the Brazos River, became a crucial hub in the buffalo hide trade.

- The fort was initially intended to protect settlers from Native American raids, but it soon became a center for buffalo hunters, skinners, and traders.

- A nearby civilian settlement, known as “The Flat” or “Hide Town,” sprang up, filled with saloons, stores, and brothels, catering to the hunters and soldiers. It was a rough and rowdy place, known for its lawlessness.

- Hunters would outfit themselves at Fort Griffin, obtaining supplies and selling their hides there.

- The town’s economy boomed due to the buffalo trade, making it a significant frontier settlement.

- The Great Slaughter (1870s): This decade witnessed the most intense period of buffalo hunting in Texas.

- Hunters, armed with powerful, large-caliber rifles like the Sharps, could kill dozens, even hundreds, of buffalo in a single day.

- The primary target was the hides, which were relatively valuable. The rest of the carcass, including tons of meat, was often left to rot on the prairie, a practice that was deeply offensive to the Native Americans who utilized every part of the animal.

- This unsustainable hunting decimated the buffalo population at an unprecedented rate.

- Key Figures and Methods:

- Professional buffalo hunters like J. Wright Mooar and others became very wealthy.

- Hunting was often done from a “stand,” where hunters would shoot multiple animals from a single position until the herd was spooked.

- Skinners worked to remove the hides, a laborious and unpleasant task.

- Impact on Native Americans: The mass slaughter of the buffalo had a devastating impact on the Plains Indians.

- Their entire way of life, which was deeply connected to the buffalo, was disrupted and threatened.

- The loss of the buffalo meant the loss of their primary food source, as well as materials for clothing, shelter, and tools.

- This destruction was a deliberate strategy by the U.S. government and military leaders like General Philip Sheridan, who believed that eliminating the buffalo would force Native Americans onto reservations and make them dependent on the government. Sheridan is famously quoted as saying that buffalo hunters had done more to subdue the Indians than the army.

The Buffalo Wars

- The diminishing buffalo herds led to increased tensions and conflicts between Native American tribes and buffalo hunters. These conflicts are sometimes referred to as the “Buffalo Wars.”

- The Red River War (1874-1875): This major conflict involved the Southern Plains tribes (Comanche, Kiowa, Cheyenne, and Arapaho) against U.S. forces.

- The Second Battle of Adobe Walls (June 27, 1874) was a significant event in this war. Buffalo hunters at Adobe Walls, a trading post in the Texas Panhandle, were attacked by a large force of Native American warriors. The hunters, though outnumbered, were able to defend themselves with their superior firearms.

- The war resulted in the final defeat of the Southern Plains tribes and their relocation to reservations in present-day Oklahoma.

- The Buffalo Hunters’ War (1876-1877):

- Also known as the Staked Plains War.

- Comanche warriors, led by Black Horse, left the reservation and attacked buffalo hunters in the Texas Panhandle.

- These conflicts highlighted the desperation of the Native Americans as their way of life was being destroyed.

- The U.S. Army played a role in protecting the buffalo hunters and suppressing Native American resistance.

Decline and Near Extinction

- Rapid Depletion: By the late 1870s and early 1880s, the vast herds of buffalo in Texas were decimated. The southern herd was virtually wiped out by 1878.

- Bone Trade: A grim industry emerged in the wake of the slaughter: the collection of the bones of the dead buffalo that littered the plains. These bones were shipped east and used to make fertilizer, bone china, and other products.

Conservation Efforts and Legacy

- Early Conservationists: Individuals like Charles Goodnight, a Texas rancher, recognized the impending extinction of the buffalo and began to preserve small herds on his ranch. His efforts, and those of others, were crucial in saving the species.

- Shifting Perspectives: Public awareness grew regarding the tragic loss of the buffalo and its impact on the ecosystem and Native American cultures.

- Modern Era: Through dedicated conservation efforts, the American bison has made a significant comeback, though its population never reached its pre-slaughter levels.

- Today, bison herds can be found in state parks, national parks, and on private ranches across Texas, serving as a reminder of the state’s natural and cultural heritage.

- The Intertribal Buffalo Council plays a key role in restoring buffalo to tribal lands, recognizing the animal’s cultural and ecological importance.

The history of buffalo hunting in Texas is a stark and tragic example of the devastating consequences of unchecked exploitation of natural resources. It also illustrates the clash of cultures and the brutal tactics used during westward expansion, with long-lasting effects on both the environment and Native American communities.

You must be logged in to post a comment.