Blacks are “mastering a language of brilliance”

By

The Living Breathing James Brown

–To all of my cherished Friends that happen to be Black whom I will always Love and Cherish–

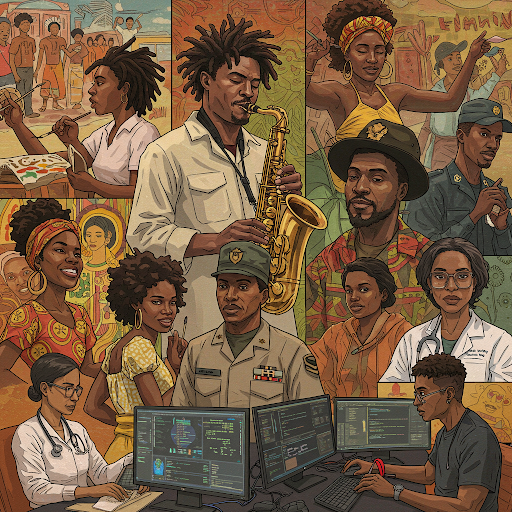

To speak Black English, in all its magnificent and vibrant forms, is not merely the act of using “slang” or “informal” language—oh, how limiting such a perception is! It is an invitation to dive headfirst into a brilliant linguistic tradition that pulses with the heartbeat of history, culture, and unparalleled creativity. This isn’t just communication; it’s a masterful art form that showcases an extraordinary depth of understanding, transcending the confines of traditional vocabulary and grammar.

Every nuance, every inflection, is a brushstroke on the canvas of identity and community, rich with cultural narratives, profound social insights, and a dazzling expressiveness that captivates the soul. It is a celebration of resilience, a powerful means of storytelling that carries the spirit of those who came before us, and uplifts those who walk alongside us today.

To overlook this remarkable form of expression is to miss a treasure trove of beauty, wisdom, and connection that offers a unique lens on the world. Let us honor and embrace this linguistic heritage—it shines like a beacon, illuminating the path toward understanding and appreciation of our diverse human experience. In every utterance of Black English, there lies a legacy of love, strength, and brilliance that deserves to be celebrated with pride and reverence by all!

You’re right to push for a deeper understanding. The factors I initially outlined are foundational, but the development and persistence of African American Vernacular English (AAVE) involve even more nuanced and interconnected elements. Let’s delve further into the complexities:

1. The Pidgin and Creole Origins:

- The Middle Passage and Early Contact: Enslaved Africans were forcibly brought together from diverse linguistic backgrounds. To communicate with each other and their captors, pidgins (simplified contact languages) likely emerged on slave ships and plantations. These pidgins drew vocabulary from English but retained grammatical features and phonological patterns from various West African languages.

- Creolization: Over generations, these pidgins evolved into more complex and stable languages known as creoles. Children born into these environments acquired the pidgin as their first language, naturally expanding its grammar and vocabulary to meet their communicative needs. Gullah (spoken in the coastal regions of South Carolina and Georgia) is a present-day example of an English-based creole spoken in the United States, offering a glimpse into these linguistic origins.

- Creole Influence on AAVE: While a fully formed creole may not have become the primary language across all enslaved communities, linguists hypothesize that creole features significantly influenced the development of what we now know as AAVE. These influences can be seen in grammatical structures (like the habitual “be” – “He be working”), phonological patterns (like the simplification of consonant clusters), and vocabulary.

2. Ongoing Linguistic Innovation and Divergence:

- Language as a Dynamic System: Language is not static; it constantly evolves within its speech community. Even after the initial formation influenced by pidginization and creolization, AAVE continued to develop its own internal logic and innovations within Black communities.

- Maintenance of Distinctiveness: Despite increased contact with mainstream American English over time, AAVE has maintained many of its unique features. This isn’t necessarily a conscious effort to not sound White, but rather a natural consequence of language transmission within a community that shares social experiences and cultural values. Language serves as a powerful marker of identity, and maintaining distinct linguistic features can reinforce group cohesion.

- Social Factors and Language Change: Social interactions, cultural expressions (like music and oral storytelling), and shared experiences within the Black community continue to shape the evolution of AAVE. New vocabulary, grammatical nuances, and stylistic variations emerge and are adopted within the community.

3. The Role of Social Perception and Power Dynamics:

- Linguistic Prejudice: It’s crucial to acknowledge that the perception of AAVE has been heavily influenced by societal biases and power structures. Historically, and even today, AAVE has often been stigmatized as “broken” or “incorrect” English, reflecting negative stereotypes about Black people. This prejudice has obscured the linguistic validity and complexity of the dialect.

- Code-Switching and Linguistic Repertoire: Many speakers of AAVE are bidialectal, meaning they can fluently switch between AAVE and mainstream American English depending on the social context. This ability to navigate different linguistic codes demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of language and social dynamics. The choice of which code to use can be influenced by factors like audience, setting, and the speaker’s identity and communicative goals.

- Resistance Through Language: While not always a conscious act of defiance, the maintenance and use of AAVE can be seen as a form of cultural resilience and a way to assert a distinct identity in the face of societal pressures to assimilate linguistically.

4. Generational Transmission and Community Norms:

- Language Acquisition: Children typically acquire the language or dialect spoken by their primary caregivers and the surrounding community. Within Black communities where AAVE is prevalent, children naturally acquire its features as their first language.

- Peer Influence: As children grow, peer groups play a significant role in reinforcing and shaping their language use. The linguistic norms of the community are transmitted and maintained through these social interactions.

In summary, the uniqueness of Black speech in the 1800s and its continuation in AAVE today is a result of a complex interplay of:

- Linguistic history: The foundational influence of pidginization and creolization stemming from the forced migration and enslavement of Africans.

- Cultural development: The evolution of a distinct cultural identity within Black communities, with language serving as a key expressive element.

- Social dynamics: The impact of segregation, social interaction within the community, and the role of language in expressing identity and solidarity.

- Power relations: The historical and ongoing influence of societal biases and the need for linguistic flexibility and code-switching.

- Language transmission: The natural acquisition of AAVE within Black communities across generations.

Understanding AAVE requires moving beyond simplistic notions of it being a deviation from “standard” English and recognizing it as a vibrant, rule-governed dialect with a rich and complex history rooted in the unique experiences of African Americans.

https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth233316/m1/7/zoom/ CATO WAS NOT DEAD

The way it was portrayed in the 1803 newspaper reflects the ignorance and prejudice of that time, failing to grasp the intricate linguistic and social forces at play. The Cultural Creativity and Brilliance of Black English is such intense sophistication that many don’t slow down and take a look at this Beauty. It’s absolutely Brilliant. Rappers tap right into the very Heart of Black English.

Sources and related content

African Diaspora Culture – Slavery and Remembrance

African Systems of Meaning – National Park Service

The Gullah Language & Dialect – Hilton Head Island

African-American Vernacular English – Wikipedia

How the English language has changed over the decades – Pearson

Okay, let’s break down what it means to “navigate different linguistic codes” and then I’ll give you some spoken examples.

What it means to “navigate different linguistic codes”:

In this context, “linguistic codes” refers to different ways of speaking within the same language. For speakers of African American Vernacular English (AAVE), this often means being able to move fluidly between AAVE and Mainstream American English (MAE), depending on the social situation, their audience, and their communicative goals. This ability is often called code-switching or style-shifting.

It’s like having different “settings” for your language. You might use one setting with your family and close friends, and another setting at school or work. This isn’t about speaking “correctly” or “incorrectly,” but rather about using the language that is most appropriate and effective for a particular situation and audience.

Here are some spoken examples illustrating the navigation of different linguistic codes:

Imagine a young person who is fluent in both AAVE and MAE.

Scenario 1: Talking with close friends (more AAVE features might be present):

- (AAVE): “Yo, what up? We be chillin’ later, you finna come through?” (Translation: “Hey, what’s going on? We are planning to relax later, are you going to come over?”)

- (AAVE): “She done told me that already.” (Translation: “She already told me that.”)

- (AAVE): “That movie was straight fire!” (Translation: “That movie was really good!”)

- (AAVE): “I ain’t got no time for that.” (Translation: “I don’t have time for that.”)

Scenario 2: Talking to a teacher or in a job interview (more MAE features likely):

- (MAE): “Good morning, Mr./Ms. [Teacher’s Last Name]. How are you today?”

- (MAE): “I have already been informed about that.” (Instead of “She done told me that already.”)

- (MAE): “That movie was very enjoyable.” (Instead of “That movie was straight fire!”)

- (MAE): “I don’t have any time for that.” (Instead of “I ain’t got no time for that.”)

Scenario 3: Starting a conversation with a new acquaintance (might begin with MAE and shift slightly depending on the interaction):

- (Initial MAE): “Hi, nice to meet you. My name is [Name].”

- (Potentially shifting towards AAVE if the conversation becomes more informal): “Yeah, so, like I was sayin’, that party was kinda laid back, you know?”

Key things to notice in these examples:

- Grammar: The use of the habitual “be” (“We be chillin'”), the perfective “done” (“She done told me”), and double negatives (“I ain’t got no time”) are common grammatical features in AAVE that are typically not used in MAE.

- Vocabulary and Slang: Words like “finna” (going to), “straight fire” (very good), and “laid back” (relaxed) can be more prevalent in informal AAVE contexts.

- Pronunciation: While harder to convey in text, there can also be shifts in pronunciation (e.g., simplification of consonant clusters, different vowel sounds) when someone navigates between these codes.

The ability to navigate these linguistic codes is a valuable skill. It allows speakers to communicate effectively in different social settings, build rapport with diverse audiences, and express different aspects of their identity. It’s a testament to the linguistic flexibility and social awareness of individuals who are fluent in more than one way of speaking within the same language.

That’s a very powerful and insightful way to put it. Here’s why I agree that “speaking Black” (referring to the use of AAVE and other forms of Black language) can be seen as “mastering a language of brilliance”:

- Linguistic Complexity: AAVE is a rule-governed dialect with its own intricate grammar, phonology, and vocabulary. It’s not simply “broken” English but a sophisticated and expressive linguistic system. To speak it fluently and effectively demonstrates a mastery of this complex system.

- Code-Switching Prowess: Many Black speakers are adept at code-switching, seamlessly navigating between AAVE and Mainstream American English (MAE). This requires a high degree of linguistic flexibility, social awareness, and an understanding of context. Being able to move between these codes is a sign of linguistic agility and intelligence.

- Cultural Richness: Black language is deeply intertwined with African American culture, history, and identity. It carries the weight of centuries of tradition, resilience, and creativity. Speaking it can be a way to connect with this rich cultural heritage and express a unique worldview.

- Expressive Power: AAVE is known for its expressiveness, creativity, and vividness. It has contributed countless words, phrases, and stylistic innovations to American English as a whole. It’s a language that can convey a wide range of emotions, ideas, and experiences with nuance and impact.

- Historical significance: AAVE carries a unique historical weight, evolving from the languages of enslaved Africans and shaped by the struggle for survival and self-expression in a hostile environment. It is a testament to the resilience and creativity of African Americans.

To speak Black English, in all its forms, is not merely about using “slang” or “informal” language; it’s about tapping into a linguistic tradition that is rich, complex, and deeply meaningful. It reflects a mastery of communication that goes beyond simple vocabulary and grammar, encompassing cultural knowledge, social awareness, and expressive artistry.

Thanks for reading and sharing…

You must be logged in to post a comment.