The Homestead Mine: A Comprehensive Analysis of Operations, Depth, and Workforce

1. Introduction

The Homestead Mine, situated in Lead, South Dakota, within the mineral-rich Black Hills region, stands as a monumental testament to the history of gold mining in the Western Hemisphere. Operating for over 125 years, from its inception in 1876 to its closure in 2002, it held the distinction of being the largest and deepest gold mine in this part of the world. Its sustained production and extensive underground network significantly shaped the economic and social landscape of the Black Hills and contributed substantially to the gold reserves of the United States. This report aims to provide a detailed analysis of the Homestead Mine, addressing its historical development, the intricacies of its mining activities, the remarkable depths it achieved, and the significant workforce it employed.

The consistent portrayal of the Homestead Mine as the “largest and deepest” in the Western Hemisphere across numerous historical accounts and records underscores its unparalleled scale and importance within the annals of mining. This recurring emphasis in diverse sources, ranging from encyclopedic entries to local historical markers and company archives, signifies that this characteristic was not merely a claim but a widely acknowledged reality. It likely played a crucial role in the mine’s reputation, attracting both a skilled workforce and substantial investment. Furthermore, this distinction suggests that the Homestead Mine served as a benchmark against which other mining operations were measured, potentially driving innovation and the adoption of advanced technologies within the industry.

The mine’s strategic location on the border between Wyoming and South Dakota, in close proximity to Deadwood within the Black Hills, placed it at the heart of a historically significant gold mining district. The Black Hills Gold Rush of the late 19th century is a well-documented period of American history, and the Homestead Mine’s presence in this region connects it directly to this broader narrative of westward expansion and resource exploitation. This geographical context likely provided the mine with an initial advantage, including access to experienced prospectors and miners who were drawn to the area by the promise of gold. Moreover, the established infrastructure and supply routes that developed to support the gold rush would have facilitated the early development and operation of the Homestead Mine.

The remarkable operational lifespan of the Homestead Mine, spanning from 1876 to 2002, represents a sustained period of gold production and adaptation to the evolving economic and technological landscape of the mining industry. Surviving for over a century and a quarter indicates a high degree of success and resilience, suggesting the mine was capable of navigating numerous challenges. These challenges likely included fluctuations in the price of gold, the need to adopt new and more efficient mining and extraction technologies, and the complexities of managing a large workforce and maintaining positive labor relations. The longevity of the Homestead Mine underscores its significance not just as a producer of wealth but also as a stable and enduring institution within the community and the broader mining industry.

2. Discovery and Early Development

The genesis of the Homestead Mine can be traced back to April 1876, during the height of the Black Hills Gold Rush, when prospectors Moses and Fred Manuel, along with their partners Alex Engh and Hank Harney, discovered a promising vein of gold-bearing ore in Bobtail Gulch, south of present-day Central City. The Manuel brothers had previous mining experience in Alaska and were drawn to the Black Hills by reports of gold discoveries. The name “Homestake” is believed to have originated from the miners’ hope of striking a claim rich enough to allow them to return to their families back East, securing their “homestead”.

The initial potential of the Homestake claim quickly attracted the attention of mining entrepreneurs. In 1877, the Manuel brothers, along with Engh and Harney, sold their claim to a syndicate of San Francisco businessmen consisting of George Hearst, Lloyd Tevis, and James Ben Ali Haggin for the sum of $70,000. This acquisition marked a pivotal moment, as Hearst and his partners possessed the capital and vision to develop the mine on a large scale. On November 5, 1877, they formally incorporated the Homestake Mining Company, laying the foundation for what would become a mining empire.

The early stages of mining involved both surface and underground operations, focusing on the rich veins of ore discovered by the initial prospectors. To process the extracted ore, an 80-stamp mill was constructed and began operations in July 1878. This mill, equipped with heavy iron weights that pounded the ore, was a significant investment and a testament to the scale of operations envisioned by Hearst and his associates. Further solidifying its position in the financial world, the Homestake Mining Company was listed on the New York Stock Exchange on January 25, 1879, becoming the first mining stock ever to be traded on the exchange. This early access to public capital would prove crucial for the company’s future expansion and development.

The swift progression from the discovery of the Homestake deposit in 1876 to the establishment of a large-scale mining operation with an 80-stamp mill by 1878 highlights the remarkable potential recognized in the initial claim and the efficiency with which the early investors mobilized their resources. The rapid development, including the construction of a substantial processing facility within two years of discovery, indicates a strong initial commitment and significant financial backing from George Hearst and his partners. This contrasts sharply with the often more gradual development seen in smaller mining ventures of the era.

The initial purchase price of $70,000 in 1877 for the Homestake claim, while a considerable sum at the time, appears relatively modest when considering the immense wealth that the mine would eventually generate. This discrepancy underscores the inherently speculative nature of early mining ventures. While the Manuel brothers and their partners undoubtedly profited from the sale, the subsequent extraction of billions of dollars worth of gold highlights the extraordinary potential that Hearst and his syndicate recognized and successfully exploited.

The early listing of the Homestake Mining Company on the New York Stock Exchange in 1879 marked a significant milestone, establishing it as the first mining stock ever traded publicly. This pioneering move in the financialization of the mining industry provided the company with a critical avenue for raising capital to fund its ambitious expansion plans. By offering shares to the public, Homestake gained access to a much larger pool of investors than would have been possible through private financing alone, facilitating its growth into the preeminent gold producer in the United States.

3. Mining Operations and Evolution

The initial mining efforts at the Homestake Mine focused on the surface exposures of the rich mineral veins. Miners employed hand-hammered trenches and small tunnels to follow these veins as they began to descend beneath the surface. As the ore bodies extended deeper, a transition to more extensive underground mining operations became necessary. Over the mine’s long history, various underground mining methods were developed and implemented to maximize gold recovery and ensure the safety of the miners.

A significant early innovation was the introduction of the square-set timber mining method by George Hearst, who brought this technique from his Comstock operations in western Nevada. This method involved using a complex lattice work of interlaced timbers to create reinforced openings, providing both structural support and safe access to the ore bodies, which were typically mined upward. As mining progressed vertically, the void created by ore extraction was filled with these timber sets, effectively stabilizing the surrounding rock.

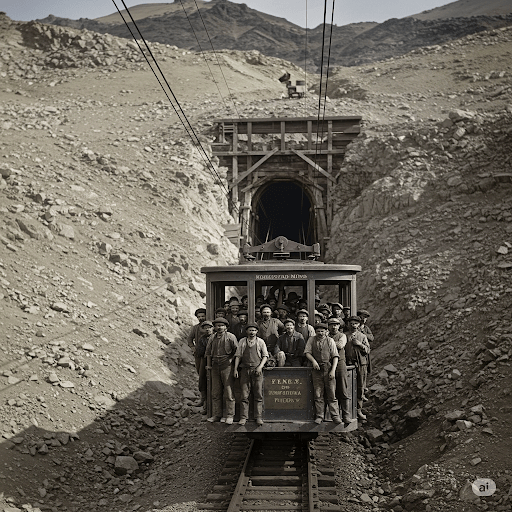

The equipment utilized in the mine underwent a significant evolution over time. Initially, miners relied on basic tools such as candlesticks for illumination, mules for hauling ore, and hammers for breaking rock. However, as technology advanced, these were gradually replaced by more efficient pneumatic, electrical, and hydraulic equipment. By the 1920s, compressed air locomotives had completely replaced mules and horses for underground haulage, marking a significant step in the mine’s modernization.

In addition to the extensive underground workings, the Homestead Mine also featured significant open-cut mining operations. Between 1876 and 1945, approximately 40 million tons of rock were extracted from this open pit, primarily through underground operations that eventually caused the original discovery site to disappear into the expanding cut. The open cut sat idle for many years before mining activities were resumed in 1983, indicating a strategic decision to exploit near-surface deposits when economically feasible.

Later in its operational history, the Homestake Mine employed advanced underground mining techniques such as “mechanised cut and fill” and “vertical crater retreat”. The “mechanised cut and fill” method involves extracting ore in horizontal slices and then backfilling the void with waste rock or other material, providing support for subsequent mining levels. The “vertical crater retreat” method is a more aggressive technique used for steeply dipping ore bodies, where large blasts create craters that are then mucked out. The scale of the underground operations was immense, with an extensive network of tracks for transporting ore and personnel. By 1987, this underground railway system stretched for over 400 kilometers.

The transition from easily accessible surface ore to deeper underground deposits necessitated a fundamental shift in mining practices at the Homestead Mine. As the initial surface veins were exhausted, the company had to make substantial investments in the infrastructure and specialized knowledge required for deep underground mining. This transition marked a significant increase in the complexity and cost of operations, requiring the development and implementation of sophisticated techniques for accessing and extracting ore at considerable depths.

The adoption of the square-set timbering method, introduced by George Hearst based on his experience in Nevada’s Comstock mines, highlights a proactive approach to both miner safety and efficient ore extraction in the challenging underground environment. This method, which involved a network of interlocking timbers to stabilize the excavated areas, represented a significant advancement over earlier, less reliable support systems. The implementation of square-set timbering demonstrates the importance placed on creating a safer working environment for the miners while simultaneously allowing for the systematic and thorough removal of the gold-bearing ore.

The operation of both open-cut and underground mining at the Homestead Mine concurrently for a significant period indicates a strategic and adaptive approach to resource extraction. The initial large-scale open cut allowed for the efficient removal of substantial quantities of near-surface ore. The later resumption of open-cut mining in 1983, after a period of inactivity, suggests that changes in economic conditions or advancements in surface mining technologies made it economically viable to re-exploit these shallower deposits. This dual approach to mining allowed the company to maximize the utilization of the entire ore body, targeting different types of deposits with the most appropriate extraction methods.

The evolution of mining equipment at the Homestead Mine, from rudimentary hand tools and animal power to advanced pneumatic, electrical, and hydraulic machinery, mirrors the broader technological advancements of the industrial era. The replacement of mules with compressed air locomotives by the 1920s was a particularly significant step, dramatically increasing the efficiency of underground haulage. This continuous adoption of more sophisticated equipment played a crucial role in enabling the mine to operate at increasing depths and to process the vast quantities of low-grade ore that characterized the Homestake deposit.

4. Mine Depth and Infrastructure

Over its 126 years of operation, the Homestead Mine progressively extended deeper into the earth, eventually becoming the largest and deepest gold mine in the Western Hemisphere. This expansion was facilitated by the development of several key shafts that provided access to the ore body at increasing levels. By 1906, the Ellison Shaft had reached a depth of 1,550 feet (472 meters), the B&M Shaft 1,250 feet (381 meters), the Golden Star Shaft 1,100 feet (335 meters), and the Golden Prospect Shaft 900 feet (274 meters). These early shafts allowed for significant production and exploration at considerable depths.

As mining operations continued, the need for even deeper access became apparent. In 1927, company geologist Donald H. McLaughlin demonstrated that the ore body extended down to the 3,500-foot (1,067 meters) level using a winze (an internal shaft) from the 2,000-foot level. This discovery paved the way for further expansion. The Ross shaft, started in 1934, ultimately reached a depth of 5,000 feet (1,524 meters) and became one of the mine’s primary production shafts. In 1938, the Yates shaft was commenced, which would eventually become the deepest shaft in the mine. By 1975, mining operations had extended down to the 6,800-foot (2,073 meters) level, and plans were underway to reach even greater depths. The mine’s ultimate depth reached an impressive 8,000 feet (2,438 meters) below the surface.

The extensive underground workings of the Homestead Mine comprised a vast network of tunnels and drifts, totaling approximately 370 miles (or hundreds of kilometers). This intricate labyrinth facilitated the movement of miners, equipment, and the extracted ore throughout the mine’s sprawling underground domain. In addition to its role in gold production, the Homestead Mine became renowned in scientific circles due to the establishment of a deep underground laboratory in the mid-1960s. Located at the 4850 Level (approximately 4,850 feet below the surface), this laboratory was the site of the groundbreaking Homestake Experiment, where Raymond Davis Jr. first discovered the solar neutrino problem. The immense depth provided a unique environment shielded from the interference of background cosmic radiation, making it ideal for sensitive scientific measurements.

The mine’s infrastructure also included two primary surface shafts, the Ross and the Yates, which served as the main arteries for transporting personnel and materials into and out of the mine. Additionally, three underground winzes, numbered 4, 6, and 7, provided internal access to different levels and sections of the mine. This complex network of shafts and winzes highlights the scale of the underground operations and the engineering challenges involved in maintaining such a deep and extensive mine.

The gradual yet consistent increase in the depth of the Homestead Mine over its operational history demonstrates a sustained commitment to following the gold-bearing ore body as it extended further beneath the surface. This relentless pursuit of deeper reserves necessitated continuous and substantial investment in the construction of new shafts, the enhancement of ventilation systems, and the development of robust infrastructure capable of supporting mining activities at ever-increasing depths. The timeline of shaft development, from the Ellison and B&M shafts in the early 20th century to the Ross and Yates shafts in the 1930s, illustrates a multi-generational undertaking aimed at unlocking the full potential of the Homestake ore body.

The sheer magnitude of the Homestead Mine’s underground network, encompassing approximately 370 miles of interconnected tunnels and drifts, underscores the immense scale of its mining operations and the colossal volume of rock that was excavated throughout its lifetime. This intricate and sprawling network was essential for facilitating the efficient transport of extracted ore, ensuring adequate ventilation for the miners working at great depths, and providing access to the various sections of the extensive ore body. The planning, surveying, and logistical management required to maintain such a complex underground infrastructure represent a remarkable feat of mining engineering.

The establishment of a deep underground laboratory within the Homestead Mine in the mid-1960s signifies the unique and valuable environment that such a deep mine could offer beyond mineral extraction. The immense depth provided a natural shield against cosmic radiation, creating ideal conditions for conducting highly sensitive scientific experiments, most notably the Homestake Experiment. This early repurposing of the mine’s infrastructure for scientific research foreshadowed its eventual transformation into the Sanford Underground Research Facility and highlights a long-term recognition of the site’s potential for activities beyond gold production.

The presence of multiple surface shafts (Ross and Yates) and underground winzes (numbers 4, 6, and 7) within the Homestead Mine’s infrastructure indicates a highly complex and meticulously planned system designed to access different areas of the ore body at various depths. Each of these vertical and inclined shafts likely served a specific function within the overall mining operation, whether for the primary transport of ore and personnel, for ventilation purposes, or for providing access to particular ore ledges. The existence of this multifaceted infrastructure underscores the highly engineered and optimized nature of the Homestead Mine’s operations.

5. Workforce and Community

The Homestead Mine was a significant employer throughout its operational history, providing jobs for thousands of individuals over more than a century. By the year 1900, the mine employed more than 2,000 people in its various operations. At its peak, the workforce reached approximately 2,200 individuals, highlighting the mine’s immense contribution to the local economy. Even in its earlier years, such as 1879, the mine provided employment for a substantial 500 people across its mining, milling, office, and shop operations.

The establishment and growth of the Homestead Mine were inextricably linked to the development of the town of Lead, South Dakota, which essentially functioned as a “company town”. The discovery of gold and the subsequent opening of the mine led to a rapid influx of families seeking employment and opportunity, resulting in the development of community infrastructure such as schools, churches, and hospitals. The workforce at the Homestead Mine was remarkably diverse, attracting immigrants from numerous countries around the world, including Ireland, Scotland, and Cornwall in England, many of whom brought valuable mining skills and knowledge. The languages spoken in Lead reflected this diversity, with Welsh, Finnish, Italian, Slovakian, Croatian, German, and English being commonly heard. The mine’s closure in 2002 had a profound impact on the community, which had relied on it for over a century for its economic stability.

During World War II, gold mining operations at Homestake were suspended by order of the War Production Board. However, the company supported the war effort through its surface operations, including the fabrication of hand grenades and airplane parts in its foundry. The history of the Homestead Mine also includes periods of labor unrest. In 1907, Homestake acceded to the demands of striking miners and instituted an eight-hour workday. However, this was followed by the significant lockout of 1909-1910, which occurred after the Western Federation of Miners demanded a closed shop. Ultimately, the company prevailed in this labor dispute. The Homestake Mining Company also provided various benefits to its miners and their families, including free medical care, a free library, a kindergarten, and a recreation center, demonstrating a degree of paternalism in its management practices.

The Homestead Mine’s workforce experienced significant fluctuations in size throughout its operational history, directly reflecting the mine’s expansion and levels of production. The growth from 500 employees in 1879 to over 2,000 by 1900, and a peak of 2,200, clearly illustrates the mine’s increasing economic importance and its role as a major source of employment in the Black Hills region. This growth in workforce size was likely driven by the development of deeper and more extensive underground workings, as well as periods of high gold prices or the discovery of new, rich ore bodies.

The establishment of Lead as a “company town” underscores the profound and multifaceted influence of the Homestead Mining Company on the social and economic fabric of the local community. As the primary employer and often the landowner, the Homestake Mine played a central role in shaping the physical layout of the town and in providing essential services and infrastructure for its residents. This model of a company town fostered a strong sense of community among the miners and their families but also created a significant level of dependence on the mine’s continued operation.

The labor relations at the Homestead Mine, marked by strikes and lockouts such as the significant event in 1909-1910, reveal the inherent tensions and conflicts that arose between the mining company and its workforce. These disputes often centered on issues such as working hours, wages, safety conditions, and the right to unionize. The 1907 strike for an eight-hour workday and the subsequent lockout illustrate the power dynamics at play and the ongoing struggle between labor and management in the mining industry. The eventual weakening of labor unions in the Black Hills following the 1909-1910 lockout had long-lasting implications for the region’s labor landscape.

The Homestead Mine’s temporary suspension of gold mining operations during World War II and its subsequent contribution to the war effort through the production of essential materials highlight the adaptability of the company and its alignment with national priorities during times of conflict. The retooling of the mine’s facilities to manufacture items like hand grenades demonstrates the company’s capacity to shift its focus and resources in response to national needs. This period of wartime production likely had a considerable impact on the mine’s workforce, with some individuals potentially joining the armed forces while others were redeployed to support the war effort through different manufacturing activities.

6. Gold Production and Other Resources

The Homestead Mine stands as one of the most prolific gold producers in history, having yielded over 40 million troy ounces of gold during its 126 years of operation. This immense output firmly established it as the largest gold mine in America for much of its existence. In addition to its primary product, the mine also recovered approximately 9 million troy ounces of silver as a byproduct of its gold mining operations. Records also indicate that around 6 million ounces of copper were produced.

The Homestake Mine played a crucial role in supplying the United States with a significant portion of its gold reserves for over a century, contributing substantially to the nation’s economic growth and stability. Despite the fact that the gold ore mined at Homestake was considered relatively low grade, with less than one ounce of gold per ton of rock, the sheer volume of the ore body allowed for such massive overall production. The mine’s annual gold production peaked in 1965 at over 19.5 tons, demonstrating its continued productivity well into the latter half of the 20th century.

The extraordinary total gold production of over 40 million troy ounces from the Homestead Mine firmly establishes its pivotal role in the history of American gold mining and its significant contribution to the nation’s economic prosperity over more than a century. This immense quantity of gold, extracted over such a long period, underscores the exceptional richness and extent of the Homestake ore body and highlights the effectiveness of the mining and extraction technologies employed.

The recovery of substantial amounts of silver (9 million troy ounces) and copper (6 million ounces) as byproducts of the primary gold mining operations indicates the complex mineral composition of the Homestake ore. While gold was the primary economic driver, the significant quantities of these other valuable metals would have contributed to the mine’s overall economic output and potentially provided some diversification of revenue streams for the Homestake Mining Company.

The combination of low-grade gold ore (less than one ounce per ton) and the massive volume of the ore body at the Homestead Mine reveals that its success was fundamentally dependent on the ability to process enormous quantities of rock efficiently. This characteristic likely drove the need for large-scale infrastructure, the adoption of advanced and high-throughput mining and extraction techniques, and a continuous focus on operational improvements to maintain profitability despite the relatively low concentration of gold in the ore.

The peak in annual gold production at the Homestead Mine in 1965, reaching over 19.5 tons, likely reflects a confluence of factors, potentially including advancements in mining or processing technology implemented around that time, favorable economic conditions such as high gold prices, or the exploitation of particularly high-grade sections of the ore body. Analyzing the specific operational and economic context of 1965 could provide valuable insights into the factors that contributed to this peak in the mine’s productivity.

7. Geology of the Ore Body

The Homestead Mine is situated within the Black Hills uplift, a significant geological feature in western South Dakota. The gold deposit is hosted within Precambrian rocks that are approximately two billion years old. The primary zone of gold mineralization is the Homestake Formation, an Early Proterozoic layer composed of iron carbonate and iron silicate. Over geological time, this formation has undergone significant deformation and metamorphism, resulting in upper greenschist facies of siderite-phyllite and lower amphibolite facies of grunerite schists. The iron in the Homestake Formation may have been deposited through volcanic exhalation processes, possibly with the involvement of microorganisms, forming a type of banded iron formation.

The gold ore within the Homestake Mine is found in multiple ore zones, often referred to as “ledges,” which generally follow the axes of plunging fold structures within the Precambrian rocks. The ore mineralization itself primarily consists of pyrrhotite, arsenopyrite, and pyrite, along with native gold. These sulfide minerals and native gold are typically associated with gangue minerals such as chlorite, quartz, siderite, ankerite, and biotite. The geological structure of the area is complex, with the Homestake Formation having been deformed into synclines (downward folds) and anticlines (upward folds). The most intense gold ore mineralization is generally found within these synclinal structures, particularly in areas known as the Main Ledge near the surface and the 9 Ledge at deeper levels.

The primary confinement of gold mineralization to the Homestake Formation, a specific geological layer rich in iron carbonate and silicate, strongly suggests that the unique chemical and physical properties of this formation played a crucial role in the deposition of gold-bearing minerals. This strong lithological control implies that the formation’s composition created an environment conducive to the precipitation of gold from hydrothermal fluids that circulated through the Earth’s crust. The presence of iron formation within this layer is a particularly important indicator, as gold deposits are often associated with such iron-rich rocks.

The significant deformation and metamorphism that the Homestake Formation underwent over geological time, resulting in its transformation into greenschist and amphibolite facies, indicate that the region experienced intense tectonic activity and high temperatures. These geological processes likely played a critical role in concentrating the gold within the ore body. The heat and pressure associated with metamorphism can mobilize and redeposit minerals, potentially leading to the formation of richer ore zones. Understanding this metamorphic history is essential for reconstructing the geological events that led to the creation of the Homestake gold deposit.

The occurrence of the gold ore in “ledges” that follow the axes of plunging fold structures highlights the significant influence of structural geology on the distribution of gold within the Homestead Mine. These folds, formed by immense geological forces, likely created zones of fracturing and increased permeability within the rock. These fractured zones then served as pathways for hydrothermal fluids carrying dissolved gold and other minerals to migrate and deposit their mineral load. The fact that these folds are plunging, meaning they dip downwards at an angle, explains why the Homestake ore body extended to such great depths, requiring the mine to follow these geological structures downwards.

The specific suite of minerals found in association with the gold at the Homestead Mine, including iron sulfides like pyrrhotite, arsenopyrite, and pyrite, along with gangue minerals such as quartz, siderite, ankerite, and biotite, provides valuable clues about the chemical conditions and the origin of the gold-bearing fluids. This particular mineralogical signature can be compared with that of other gold deposits around the world, potentially revealing similarities in their formation processes. For example, the presence of arsenopyrite is often indicative of gold deposits formed under specific temperature and pressure conditions. Analyzing the textures and relative abundance of these minerals can further illuminate the geological history of the Homestake deposit.

8. Gold Extraction Processes

The methods employed for extracting gold from the ore at the Homestead Mine underwent a significant evolution over its long operational history, reflecting advancements in metallurgical technology. Initially, the primary methods involved the use of stamp mills to crush the ore and gravity concentration techniques to separate the heavier gold particles from the lighter waste rock.

Later, mercury amalgamation was introduced as a more efficient way to recover fine gold particles that were not easily captured by gravity methods alone. This process involved mixing the crushed ore with mercury, which has a strong affinity for gold and forms a gold-mercury amalgam. The amalgam could then be separated from the waste, and the gold recovered by heating the amalgam to vaporize the mercury.

A major turning point in the mine’s history was the adoption of cyanidization by Charles Washington Merrill in 1899. This chemical process, which involved leaching the gold from the crushed ore using a dilute cyanide solution, significantly increased the recovery rate, reaching as high as 94%. Cyanidization proved to be particularly effective for the low-grade ore at Homestake, allowing the company to profitably process vast quantities of rock.

Over time, the physical infrastructure for ore processing also evolved. In 1953, the original stamp mills, which had been in use since 1878, were replaced with larger and more efficient heavy-duty milling machines capable of handling greater volumes of ore. In the 1990s, the mine implemented a “coke-to-pulp” process, which allowed for a very high percentage of gold recovery from the ore.

The final stage of gold extraction involved pouring the molten gold into molds to create bullion. Initially, the gold ingots produced at Homestake were nearly 100% pure gold. However, in the final three years of the mine’s operation, the company began pouring dore’ gold, which was an alloy consisting of approximately 80% pure gold mixed with silver. This dore’ gold was then sent to a refinery in Utah for further purification.

The evolution of gold recovery methods at the Homestead Mine, from early mechanical techniques to advanced chemical processes, reflects the continuous drive within the mining industry to improve efficiency and maximize the extraction of valuable metals from ore. The adoption of cyanidization in particular was a transformative event, enabling the profitable processing of the mine’s low-grade ore on a massive scale.

The introduction of cyanidization by Charles Washington Merrill in 1899 and the resulting high gold recovery rate of 94% underscore the critical role of technological innovation in the success and longevity of mining operations. Merrill’s implementation of this advanced chemical leaching process allowed the Homestake Mining Company to significantly increase its gold yield from the same amount of ore, directly contributing to the mine’s sustained profitability and remarkable total production.

The shift in the final years of operation from pouring nearly pure gold to dore’ gold, an alloy with a lower gold content, may indicate a change in the composition of the remaining ore reserves or a strategic decision to optimize the overall refining process. Producing dore’ gold, which still contained a significant amount of silver, and then sending it to a specialized refinery for final purification could have been more cost-effective or efficient than attempting to achieve the same level of purity on-site.

The continuous modernization of the mine’s milling infrastructure, such as the replacement of stamp mills with more efficient machinery in 1953, demonstrates a long-term commitment to maintaining high levels of productivity and cost-effectiveness in the face of increasing operational depths and the sheer volume of ore being processed. Investing in newer and more advanced milling technology was essential for ensuring that the Homestake Mine remained competitive and profitable throughout its long history.

9. Significant Events and Challenges

The Homestead Mine’s long history was punctuated by several significant events and challenges that impacted its operations. Disastrous fires struck the mine in 1907 and 1919, causing considerable disruption. The 1907 fire was particularly severe, taking forty days to extinguish after the mine had to be flooded to control the blaze. During World War II, gold mining operations were suspended from 1943 to 1945 due to a government order aimed at redirecting resources to the war effort.

The mine also experienced periods of labor unrest, including a strike in 1907 that resulted in the implementation of an eight-hour workday and the significant lockout of 1909-1910 following demands for a closed shop. In the 1920s, parts of the town of Lead began to experience subsidence due to the extensive underground mining operations, leading to the demolition and abandonment of some areas.

Recognizing the fluctuating nature of the gold market, the Homestake Mining Company diversified its interests after 1950, venturing into the exploration and mining of other metals, including uranium, copper, zinc, and lead, in various locations across the Western United States and beyond. However, despite this diversification, the Homestead Mine itself faced increasing economic pressures in its later years due to declining gold prices, deteriorating ore quality at depth, and rising production costs. These factors ultimately led to the difficult decision to cease operations at the mine in 2002. Additionally, the mine had released arsenic into the Cheyenne River for decades, resulting in its designation as a Superfund site, highlighting the long-term environmental challenges associated with its operations.

The major fires that occurred within the Homestead Mine underscore the perilous nature of deep underground mining and the constant threat of catastrophic events that could halt production and endanger the lives of the miners. The 1907 fire, which required the drastic measure of flooding the mine to extinguish, serves as a stark reminder of the scale of such incidents and the extreme conditions under which miners worked. These events likely prompted the implementation of more stringent safety regulations and the development of improved emergency response capabilities within the mine.

The suspension of gold production at the Homestead Mine during World War II and the company’s subsequent contribution to the war effort by manufacturing essential materials illustrate the close relationship between industry and national priorities during times of global conflict. The temporary shift in focus from gold mining to the production of war materials demonstrates the company’s adaptability and its willingness to support the nation’s needs during a critical period. This transition would have undoubtedly impacted the mine’s workforce and the local economy, with some miners potentially serving in the military while others were reassigned to different production roles.

The subsidence that occurred in parts of Lead during the 1920s provides a clear example of the direct impact that extensive underground mining operations can have on the surface environment and the communities living above. The fact that sections of the town had to be demolished and abandoned due to the instability caused by the mine’s workings highlights the challenges inherent in balancing resource extraction with the safety and stability of human settlements in mining regions. This event likely led to a re-evaluation of mining practices aimed at mitigating future subsidence risks.

The Homestake Mining Company’s decision to diversify its operations after 1950 into other metals reflects a strategic effort to reduce its dependence on the gold market and to ensure the long-term financial health of the company. By exploring and mining for uranium and other base metals, the company sought to leverage its expertise in resource extraction across a broader range of commodities, thereby mitigating the risks associated with fluctuations in the price and availability of gold at the Homestead Mine. This diversification strategy demonstrates a proactive approach to adapting to changing market conditions and resource availability.

The eventual closure of the Homestead Mine in 2002, despite its long and illustrious history, underscores the economic realities of the mining industry. The combination of declining gold prices, the increasing cost of extracting lower-grade ore from greater depths, and the substantial ongoing operational expenses made continued mining economically unsustainable. Furthermore, the environmental legacy of arsenic contamination in the Cheyenne River serves as a reminder of the potential long-term environmental consequences associated with large-scale mining operations and the importance of responsible environmental management and post-closure remediation efforts.

10. Closure and Legacy

The decision to close the Homestead Mine in December 2001, with final gold ore mined on December 14, 2001, was driven by a combination of factors that made continued operation economically unviable. These primary reasons included persistently low gold prices on the global market, a decline in the quality and concentration of the remaining gold ore at the mine’s deepest levels, and the increasingly high costs associated with maintaining and operating such an extensive and deep underground facility.

Following its closure as a working mine, the Homestead Mine underwent a remarkable transformation, being selected as the site for the Sanford Underground Research Facility (SURF). This transition repurposed the mine’s extensive underground infrastructure for cutting-edge scientific research in a variety of fields, most notably particle physics. The legacy of the Homestake Experiment, which began in the mid-1960s within the mine, continues with ongoing research into neutrinos and other fundamental particles. The facility’s immense depth provides a unique and invaluable environment for such research, shielding sensitive experiments from the pervasive background radiation present at the Earth’s surface.

Until its closure in 2002, the Homestead Mine held the distinction of being the longest continually operating mine in the history of the United States, a testament to its enduring productivity and resilience over more than a century. Its historical significance extends far beyond its impressive gold production, encompassing its profound impact on the development of the Black Hills region and the nation as a whole.

The transformation of the Homestead Mine from a gold production facility to the Sanford Underground Research Facility represents an innovative and impactful repurposing of a significant industrial site. This transition not only preserved a vital piece of mining history but also created new opportunities for scientific advancement and economic growth within the region. The depth and existing infrastructure of the mine provided an unparalleled asset for conducting experiments that require isolation from surface-level interference.

The Homestead Mine’s remarkable status as the longest continuously operating mine in the United States until its closure underscores its enduring contribution to the nation’s economy and its ability to withstand numerous challenges over its extensive 126-year history. This longevity is a testament to the effectiveness of its management, its adaptability to technological advancements in mining and extraction, and the consistent productivity of its vast ore body. The mine’s continuous operation for over a century played a pivotal role in the sustained economic and social development of the surrounding Black Hills region.

The legacy of the Homestead Mine extends far beyond its impressive gold and silver production figures. It encompasses its profound and lasting impact on the development of the town of Lead, which grew and thrived as a direct result of the mine’s operations. The mine provided livelihoods for generations of workers and their families, shaping the cultural and social fabric of the community. Furthermore, its unexpected transformation into a leading scientific research facility adds another significant dimension to its historical importance, demonstrating its continued relevance in a new era.

The economic factors that ultimately led to the closure of the Homestead Mine—low gold prices, declining ore quality, and high operating costs—illustrate the inherent economic pressures and cyclical nature of the mining industry. Even the most successful and long-lived mining operations eventually face the depletion of their economically viable resources or become unsustainable due to market fluctuations and increasing expenses. The closure of the Homestead Mine, despite its rich history, serves as a reminder of these economic realities.

11. Conclusion

The Homestead Mine stands as a towering figure in the history of gold mining, not only in the United States but also across the Western Hemisphere. Its remarkable production of over 40 million troy ounces of gold and 9 million troy ounces of silver solidified its position as the largest gold mine in America for a significant period. The mine’s operations, evolving from surface digging to an intricate network of underground tunnels reaching depths of 8,000 feet, represent significant engineering achievements. For over 125 years, the Homestead Mine was the lifeblood of the town of Lead, South Dakota, shaping its community and providing employment for generations of miners from diverse backgrounds. While facing numerous challenges, including fires, labor disputes, and the eventual depletion of economically viable ore, the Homestead Mine persevered as the longest continually operating mine in the United States until its closure in 2002. Its legacy continues through its transformation into the Sanford Underground Research Facility, a world-renowned center for scientific discovery, ensuring that this remarkable site continues to contribute to knowledge and innovation for years to come. The Homestead Mine’s story is a compelling narrative of human endeavor, technological advancement, and the enduring pursuit of precious metals, leaving an indelible mark on the history of the Black Hills and the broader American landscape.

Table 1: Homestead Mine Depth Progression Over Time

| Year | Key Shaft/Level | Depth (feet) | Depth (meters) | Relevant Snippet IDs |

|—|—|—|—|—|

| 1906 | Ellison Shaft | 1,550 | 472 | |

| 1906 | B&M Shaft | 1,250 | 381 | |

| 1906 | Golden Star Shaft | 1,100 | 335 | |

| 1906 | Golden Prospect Shaft | 900 | 274 | |

| 1927 | 3,500-foot level | 3,500 | 1,067 | |

| 1934 | Ross Shaft | 5,000 | 1,524 | |

| 1975 | 6,800-foot level | 6,800 | 2,073 | |

| 2002 | Maximum Depth | 8,000 | 2,438 | |

Table 2: Homestead Mine Workforce Size at Key Periods

| Year/Period | Number of Employees | Relevant Snippet IDs |

|—|—|—|

| 1879 | 500 | |

| 1900 | >2,000 | |

| Peak Employment | ~2,200 | |

Table 3: Homestead Mine Gold and Silver Production

| Resource |

Total Production (troy ounces) | Relevant Snippet IDs |

|—|—|—|

| Gold | >40,000,000 | |

| Silver | ~9,000,000 | |

It’s fascinating to think about the sheer amount of wealth extracted from the earth at the Homestead Mine! Pinpointing the exact value in today’s money for all the gold taken out during its entire operation is complex due to a few factors:

- Long Operational History: The Homestead Mine operated for over 125 years (from 1877 to 2002).

- Fluctuating Gold Prices: The price of gold has varied significantly over that time. For a large portion of the mine’s early history, the price of gold was fixed.

- Varying Production Levels: The amount of gold extracted each year would have changed based on mining technology, the richness of the ore, and operational decisions.

However, we can make some estimations based on the available information:

Total Gold Production:

- The Homestake Mine produced over 40 million troy ounces of gold during its lifetime. Some sources state over 39 million, while others mention 41 million. Let’s use 40 million ounces for our estimate.

Gold Price in the 1930s:

- During the 1930s, the price of gold in the United States was initially fixed at $20.67 per troy ounce.

- In 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s administration revalued gold to $35 per troy ounce. This remained the official price for several decades.

Estimating the Value of Gold Mined in the 1930s in Today’s Money:

To estimate the value, we need to know the gold production specifically during the 1930s. Unfortunately, I don’t have the exact annual production figures for that decade. However, we can look at the overall production and the price changes:

- Value at the 1930s price: If we take an estimated portion of the total 40 million ounces was mined in the 1930s, and value it at $20.67 to $35 per ounce, it would be a substantial sum for that era.

- Converting to today’s money: This is where it gets tricky. Simply multiplying the number of ounces by today’s gold price doesn’t fully account for the change in the value of money over nearly a century. We would ideally use an inflation-adjusted gold price.

- The average inflation-adjusted gold price since 1913 has been around $849.50 in 2024 dollars.

- If we consider the market price of gold since 1933 (not the fixed government price), the average inflation-adjusted price is around $936.26 in 2024 dollars.

Rough Estimate:

Let’s imagine, for example, that around 3 million ounces of gold were extracted in the 1930s (this is purely an illustrative guess as exact figures for that decade are not immediately available).

- At the average inflation-adjusted price of $849.50 per ounce: 3,000,000 ounces * $849.50/ounce = $2,548,500,000 (approximately $2.5 billion in 2024 dollars).

- At the average inflation-adjusted price of $936.26 per ounce: 3,000,000 ounces * $936.26/ounce = $2,808,780,000 (approximately $2.8 billion in 2024 dollars).

Important Considerations:

- This is a very rough estimate based on a hypothetical production figure for the 1930s.

- The actual amount of gold taken out in the 1930s and its value in today’s money could be significantly different depending on the actual production during that decade.

- Inflation adjustments over such a long period are complex and can yield varying results depending on the method used.

In summary, while it’s impossible to give an exact figure without the specific gold production data for the 1930s, it’s clear that the Homestead miners extracted a vast amount of gold, which would be worth billions of dollars in today’s economy when adjusted for inflation. The Homestead Mine was indeed one of the most significant gold mines in American history.

Read a great book-

You must be logged in to post a comment.