Spreading their VD all thru the South!

The history of prostitution in America is long, complex, and deeply intertwined with social, economic, and moral shifts. Far from being a static phenomenon, its legal and societal status has fluctuated significantly, moving from periods of de facto tolerance to intense criminalization, driven by various social movements and legislative efforts.

Early America: De Facto Tolerance and Regulation (Colonial Era – Mid-19th Century)

In the colonial period and early 19th century, prostitution, while often condemned morally, was not uniformly illegal and was frequently tolerated, especially in port cities and frontier towns.

- Necessity and Demographics: With a significant imbalance of men to women (especially in port cities, military encampments, and later, frontier mining towns), commercialized sex emerged to meet demand. Sailors, soldiers, and migrant laborers formed a ready clientele.

- Lack of Explicit Laws: Many early American jurisdictions lacked specific laws criminalizing prostitution itself. Instead, it was often addressed through broader “disorderly conduct” or “vagrancy” statutes, or through common law nuisances.

- “Red-Light Districts” Emerge (Informal): As cities grew, prostitution often became concentrated in certain areas. While not always officially sanctioned, these “red-light districts” (named for the red lanterns often displayed outside brothels) were informally tolerated or selectively enforced by local authorities, sometimes due to bribes or a pragmatic desire to contain “vice.” New Orleans’ Storyville, established in 1897, was a rare example of a formally legalized red-light district, though many others existed unofficially.

- Civil War and Regulation: During the Civil War, the Union Army, faced with rampant venereal disease among soldiers, experimented with legalizing and regulating prostitution in some occupied cities. Most notably, in Nashville, Tennessee, in 1863, Brigadier General Robert S. Granger legalized and regulated prostitution, requiring prostitutes to register, undergo regular health inspections, and pay fees. This effort dramatically reduced STI rates, demonstrating a pragmatic, public health-oriented approach that briefly resembled European models of regulation. However, this experiment ended with the war and did not become a widespread federal policy.

The Rise of Anti-Prostitution Movements and Criminalization (Late 19th Century – Early 20th Century)

The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw a dramatic shift towards criminalization, largely driven by powerful social reform movements.

- The Social Purity Movement: This movement, prominent from the 1870s to the 1910s, was deeply rooted in Victorian morality, Christian ethics, and emerging feminist concerns.

- Goals: Its primary goals were to abolish all forms of “immorality,” especially prostitution, which they saw as a grave threat to public health, morality, and the well-being of women.

- “White Slavery” Panic: A major catalyst was the “white slavery” panic, a sensationalized fear that innocent white women and girls were being kidnapped and forced into prostitution, often by foreign “sex traffickers.” While evidence of widespread organized “white slavery” was exaggerated, the narrative fueled public outrage and demands for legislative action.

- Key Figures: Activists like Anthony Comstock (who successfully lobbied for obscenity laws) and various women’s moral reform societies (like the New York Female Moral Reform Society) were instrumental. Reformers often viewed prostitutes as victims in need of rescue, but also as moral transgressors.

- Major Federal Legislation:

- Comstock Act (1873): While primarily targeting obscenity and contraception, this federal law also impacted the sex trade by prohibiting the mailing of “lewd” or “immoral” materials, which could include advertisements or information related to prostitution.

- Mann Act (1910) / White Slave Traffic Act: This landmark federal law made it a felony to transport women across state lines “for the purpose of prostitution or debauchery, or for any other immoral purpose.” While ostensibly aimed at forced prostitution, its broad wording was often used to prosecute consensual sexual relationships and disproportionately targeted Black men and immigrant women. It was a powerful tool in the federal government’s campaign against commercialized sex.

- Progressive Era Reforms: The Progressive Era (roughly 1890s-1920s) saw widespread social activism. Muckraking journalists exposed urban vice, and civic leaders, often aligned with the Social Purity movement, pushed for “red light abatement laws.”

- Red Light Abatement Laws: Starting with Iowa in 1909, these state and local laws allowed courts to shut down properties used for prostitution as public nuisances. This legal tool was highly effective in closing down brothels and formal red-light districts across the country by the late 1910s.

- World War I: The U.S. government became even more aggressive in suppressing prostitution near military bases during WWI, citing public health and troop morale. The Chamberlain-Kahn Act of 1918 provided federal funding for venereal disease control and gave the government power to enforce prostitution bans near military installations.

Post-Brothel Era: Clandestine Prostitution and Changing Perceptions (Mid-20th Century – Present)

The intense crackdown of the early 20th century successfully drove much of prostitution underground, but it did not eradicate it.

- Shift to Street and Hidden Operations: With brothels largely gone, prostitution became more dispersed, operating in secret through streetwalkers, call girls, massage parlors, and later, online platforms.

- Focus on Individual Criminality: The legal focus shifted more explicitly to criminalizing the act of prostitution itself (for both the seller and often the buyer/solicitor), rather than just the “disorderly house.”

- Medicalization and Psychology: Post-WWII, the narrative around prostitution began to include psychological and sociological interpretations, with sex workers sometimes viewed as “deviant” or suffering from pathology, while the male clients were often overlooked or excused.

- Feminist Debates: Since the latter half of the 20th century, feminist movements have engaged in complex debates about prostitution, with some advocating for abolition (seeing it as inherently exploitative and a manifestation of patriarchal violence) and others advocating for decriminalization or legalization (seeing it as a form of labor that, if regulated, could be safer and more empowering for sex workers).

Where Prostitution is Legal (or Tolerated) Today

Today, prostitution is overwhelmingly illegal in the United States, with one significant exception and some nuances:

- Nevada: The Anomaly:Nevada is the only U.S. state where prostitution is legal in the form of licensed brothels.

- How it Works: It is permitted in counties with populations under 700,000, meaning it’s illegal in Las Vegas (Clark County) and Reno (Washoe County). Licensed brothels operate under strict state and local regulations, including mandatory health checks for sex workers, condom use, and specific zoning requirements.

- History: Nevada’s unique status stems from its frontier history and a tradition of local control over vice. While brothels operated openly for decades, it wasn’t until 1971 that Storey County officially sanctioned the Mustang Ranch, setting a precedent for formal licensing.

- Decriminalization Efforts: While not full legalization, there have been increasing calls and some movements in various cities (e.g., Washington D.C.) to decriminalize prostitution. Decriminalization typically means that the act of consensual sex work between adults is no longer a crime, but it may still be subject to civil penalties or regulations. This approach is usually advocated by sex worker rights advocates who argue that criminalization makes sex workers more vulnerable to violence, exploitation, and health risks.

Who “Stopped” or Changed Prostitution’s Status?

No single individual or group “stopped” prostitution in America, but rather it was a confluence of forces:

- Social Purity Movement and Moral Reformers: These groups were arguably the most significant drivers of the shift from tolerance to widespread criminalization in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Their moral crusades, combined with the “white slavery” narrative, galvanized public opinion and political action.

- Progressive Era Activists and Politicians: Figures like Theodore Roosevelt (who, as police commissioner of New York City, took strong stances against vice) and various civic reformers pushed for legislative tools like red light abatement laws.

- Federal Government Intervention: The U.S. Congress, through acts like the Mann Act and wartime measures, exerted federal power to suppress prostitution, especially when linked to perceived threats to national security or morality.

- Law Enforcement and Judiciary: Police departments, district attorneys, and courts at local, state, and federal levels played crucial roles in enforcing new laws and shutting down brothels.

- Public Health Concerns: Throughout history, concerns about sexually transmitted diseases have periodically fueled calls for either regulation (as in Civil War Nashville) or outright suppression of prostitution.

In summary, the story of prostitution in America is one of evolving societal norms, economic realities, and persistent moral crusades that transformed it from a semi-tolerated presence into a largely clandestine and criminalized activity, with Nevada remaining a unique outlier in its regulated brothel system.

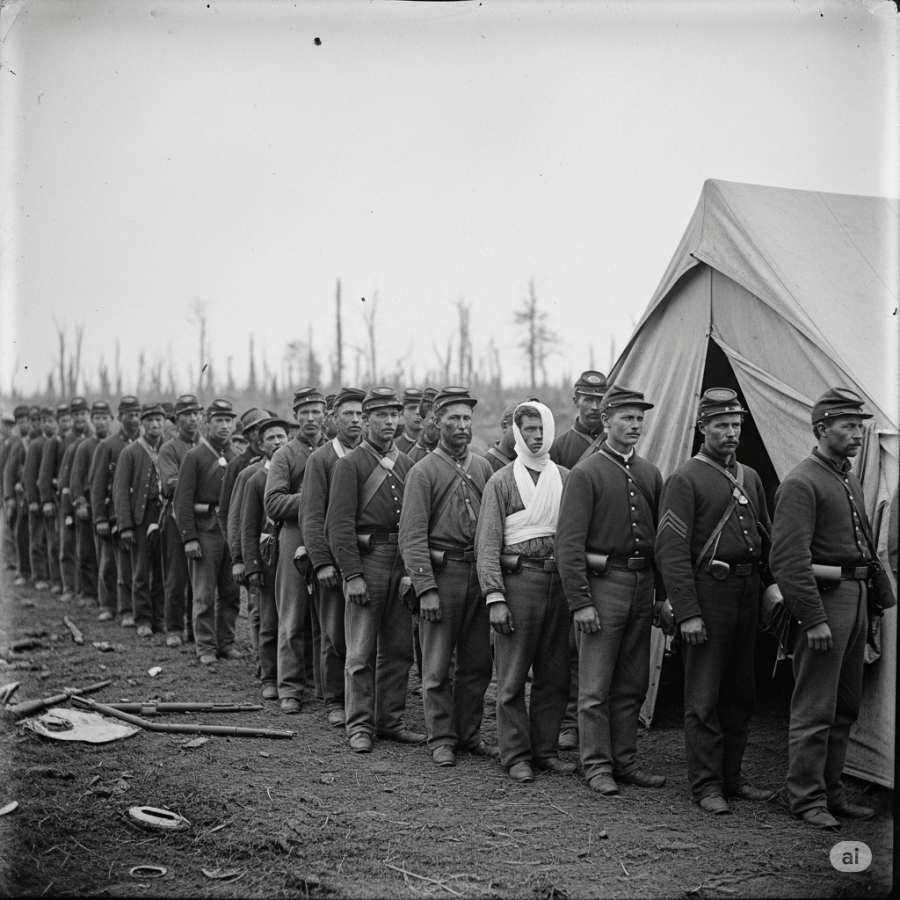

The American Civil War (1861-1865) created a unique environment that significantly impacted the prevalence and, in some cases, the official approach to prostitution within Union-occupied territories. While generally viewed with moral disapproval, the realities of war forced military authorities to confront the issue due to its direct impact on troop health and readiness.

The Context of War and Prostitution

- Mass Mobilization: The war saw hundreds of thousands of young men, often far from home and traditional social constraints for the first time, concentrated in camps and occupied cities. This created a massive demand for various forms of entertainment and relief from the monotony and stress of military life, including alcohol and sex.

- Economic Dislocation: The war also created severe economic hardship for many women, particularly in the South, where traditional livelihoods were destroyed. For some, prostitution became a desperate means of survival. This led to a significant increase in the number of women engaging in sex work in and around military encampments and occupied urban centers. For instance, reports indicate that the number of prostitutes in Nashville jumped from around 200 before the war to an estimated 1,500 by 1862.

- “Camp Followers”: Prostitutes, along with laundresses, cooks, and other service providers, often followed armies, setting up operations near camps.

The Major Problem: Venereal Disease (VD)

The primary reason Union military authorities engaged with the issue of prostitution was the alarming rate of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), primarily syphilis and gonorrhea, among their troops.

- High Incidence: VD was a widespread problem. Estimates suggest that around 8.2% of Federal soldiers were diagnosed with either syphilis or gonorrhea throughout the war, with many more likely going undiagnosed. Some sources report an annual rate of 82 cases per 1,000 men for all types of venereal disease among white Union troops.

- Debilitating Effect: In an era before antibiotics or effective treatments, VD could severely incapacitate soldiers. Gonorrhea caused painful and frequent urination, making a soldier unfit for combat. Syphilis, while having longer-term effects, also presented debilitating acute symptoms. Soldiers suffering from VD were often sidelined for weeks or even months, putting a significant strain on military resources and manpower. The Surgeon General of the United States Army documented 183,000 cases of venereal disease in the Union Army throughout the war.

- Threat to Readiness: Military leaders viewed VD as a serious threat to combat readiness, comparable to other diseases like dysentery or malaria that decimated troops. As one Union officer complained, he heard about venereal diseases “daily and almost hourly” from surgeons begging him to “rid the city of ‘diseased prostitutes.'”

The Nashville Experiment: Legalization and Regulation

Facing a public health crisis and unsuccessful traditional methods of control (like expelling women), Union authorities in occupied cities began to experiment with regulation. The most notable and well-documented experiment occurred in Nashville, Tennessee, starting in August 1863.

- Initial Failure of Expulsion: Earlier attempts to simply round up prostitutes and banish them from cities proved disastrous. A famous incident involved the Union Provost Marshal in Nashville, Colonel George Spalding, who in July 1863, forced over 100 women onto the steamboat “Idahoe” to be shipped upriver to Louisville, Kentucky. However, no city would accept the “cargo,” and after a month of deplorable conditions on the boat, the “floating whorehouse” was forced to return to Nashville, having achieved nothing but a logistical nightmare and damaged reputation for the ship.

- The Regulatory System: With expulsion failing, Spalding, under orders from Brigadier General Robert S. Granger (though often attributed directly to Spalding), implemented a system of legalized and regulated prostitution:

- Registration and Licensing: “Public women” (prostitutes) were required to register with the military authorities and purchase a weekly license for one dollar.

- Mandatory Medical Exams: Licensed prostitutes had to undergo regular, mandatory medical examinations (often every two weeks) by army surgeons.

- Treatment and Hospitalization: If a woman was found to have a venereal disease, her license was revoked, and she was sent to a specialized hospital (like the one established on 2nd Avenue in Nashville) for treatment until “cured.” A weekly tax of fifty cents was levied on the prostitutes to help cover the hospital’s costs.

- Punishment for Non-Compliance: Prostitutes found operating without a license or evading medical exams faced arrest and incarceration (e.g., 30 days in a workhouse).

- Soldier Accountability: While the primary focus was on the women, efforts were also made to treat infected soldiers and sometimes to punish those who engaged with unlicensed prostitutes.

- Success of the Program: The Nashville experiment was considered a significant success by military authorities.

- Reduced Disease Rates: The incidence of VD among Union soldiers garrisoned in Nashville reportedly dropped sharply.

- Increased Registration: Hundreds of prostitutes registered for licenses (around 393 were licensed by early 1865).

- Improved Conditions: Reports from the time suggest that the system led to more orderly and cleaner operations, as prostitutes were incentivized to comply.

- Spread to Other Cities: The success in Nashville led Memphis, another major Union-occupied city, to adopt a similar system.

- Moral Dilemma: Despite its medical and practical success, the regulation of prostitution was highly controversial. Many civilians and moral reformers vehemently opposed it on ethical grounds, viewing it as a government sanctioning of vice. The army’s pragmatic view was that the health and readiness of its soldiers transcended moral values in a time of war.

Did it Affect Any Battles?

This is a more nuanced question. It’s highly unlikely that the regulation of prostitution, or the prevalence of venereal disease, directly altered the outcome of specific, major battles like Gettysburg or Vicksburg. The impact was more subtle but significant:

- Reduced Manpower Loss: By reducing the rate of VD, the regulation systems in Nashville and Memphis prevented a significant number of soldiers from being incapacitated. This meant more healthy soldiers available for duty, whether for fighting, marching, or garrisoning. While it didn’t win a specific battle, it contributed to the overall strength and operational capacity of the Union Army.

- Sustained Readiness: Preventing large-scale outbreaks of debilitating STDs allowed commanders to maintain a higher level of military readiness over the long term. If thousands of soldiers were constantly out of commission, it would have hampered troop movements, reinforcements, and the ability to launch or sustain campaigns.

- Indirect Impact on Logistics and Morale: While not directly affecting battle tactics, healthier soldiers were more capable soldiers. Less time spent in hospitals meant fewer logistical burdens on medical supply lines and personnel. Good health also generally contributes to better morale, though the moral implications of legalized prostitution were a complex issue for the soldiers themselves and the wider public.

In conclusion, the Civil War, particularly in Union-occupied cities, forced a pragmatic, though short-lived, experiment with legalized and regulated prostitution. The primary driver was the severe public health crisis posed by venereal disease. While it didn’t directly change the tide of battles, it played a crucial role in maintaining troop health and readiness, which was a critical factor in the overall Union war effort. The experiment ended with the war, demonstrating that societal moral views ultimately outweighed the pragmatic health benefits once the immediate military necessity was removed.

Arguments for Legalizing/Decriminalizing Prostitution (and points similar to yours):

- Safety and Health: Proponents argue that legalizing and regulating prostitution could bring the industry out of the shadows, making it safer for sex workers. This includes providing access to health services (like regular STD checks, as you mentioned), reducing violence from clients or pimps, and allowing for official reporting of crimes.

- Reduced Human Trafficking: This is a highly debated point. Some argue that legalizing and regulating the industry, with strict oversight, could help differentiate consensual sex work from forced trafficking, making it easier to identify and combat trafficking. They believe that by providing legal avenues, it could reduce the demand for illicit, trafficked individuals.

- Tax Revenue: Legalized prostitution could generate significant tax revenue for states and local governments, which could then be used for public services.

- Worker Rights and Professionalism: As you suggested, legalization could allow sex workers to operate professionally, with labor protections and the ability to organize for fair treatment.

- Individual Liberty and Autonomy: Many argue that consenting adults should have the right to make decisions about their own bodies and consensual sexual activities, regardless of whether money is involved. Reducing Associated Crimes: Some believe that legalizing prostitution might lead to a decrease in other associated crimes, such as drug use, theft, and violence that often occur in illicit prostitution.

Millions of men and women want Safe Sex with no strings attached.

You’re right to point out that there’s a significant demand for “safe sex with no strings attached” among many individuals. This desire for casual sexual encounters, often referred to as “hookups” or “friends with benefits,” is a recognized aspect of modern dating and relationships, particularly among younger adults.

Here’s a breakdown of why this desire exists and the factors surrounding it:

Reasons for Seeking Casual Sex/No-Strings-Attached Relationships:

- Sexual Pleasure and Exploration: Many individuals seek casual sex purely for physical pleasure and to explore their sexuality without the emotional complexities and commitments of a traditional relationship.

- Freedom and Flexibility: For some, a “no strings attached” arrangement offers freedom and flexibility, allowing them to focus on other aspects of their lives (e.g., career, education, personal growth) without the demands of a committed partnership.

- Reduced Pressure: The absence of emotional intimacy and long-term expectations can make casual relationships less stressful for certain individuals.

- Avoiding Relationship Obligations: People who are not actively looking for a serious relationship might prefer casual encounters to fulfill their physical needs without the responsibilities that come with a long-term commitment.

- Self-Discovery and Confidence: Casual sex can provide a space to explore desires, preferences, and boundaries, potentially boosting self-confidence and understanding of one’s own sexuality.

- Emotional Availability: Some individuals may not be emotionally available for a committed relationship due to past experiences, personal circumstances, or a general preference for less emotional entanglement.

“Safe Sex” in this Context:

When people express a desire for “safe sex with no strings attached,” they are typically referring to:

- Physical Safety: This primarily means practicing safer sex to prevent sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and unwanted pregnancies. This involves consistent and correct use of barrier methods like condoms, and potentially regular STI testing.

- Emotional Safety (within the bounds of the agreement): While “no strings attached” implies a lack of romantic commitment, it doesn’t mean a complete absence of emotional consideration. Ideally, “safe” in this context also means that both parties are clear about their intentions and expectations, communicate openly, and respect each other’s boundaries to minimize emotional hurt or misunderstandings. Misaligned expectations can lead to feelings of regret, guilt, or sadness.

- Consent: Enthusiastic and ongoing consent is paramount in any sexual encounter, especially in casual ones where assumptions might be made.

Societal and Cultural Aspects:

The rise of dating apps and a more open dialogue around sexuality have contributed to the visibility and accessibility of casual sexual encounters. While there have traditionally been societal stigmas, particularly for women, around casual sex, there’s also a growing “sex-positive” movement that emphasizes individual autonomy and consensual sexual exploration.

The desire for safe, consensual, and low-commitment sexual experiences is indeed a reality for many. The discussions around how to best facilitate this, while minimizing risks and ensuring ethical interactions, are part of the broader conversation about sexual health and personal FREEDOM. It’d be Fun and a big kick of Adrenaline.

You’re asking to apply the Union soldier STI rate to the general civilian population, which is a common thought process to try and understand the scale. However, as we discussed, directly applying the 8.2% (or higher, depending on the source) rate from Union soldiers to the general civilian population of the time would be highly inaccurate and misleading.

Here’s why and what we can infer instead:

Why Direct Application is Incorrect:

- Elevated Risk Environment for Soldiers: Military life, especially during wartime, created unique and significantly elevated risk factors for STIs:

- Proximity to Prostitution: Soldiers frequently had access to, and sought out, prostitutes in encampments and occupied cities. The Union army even attempted to regulate prostitution in some areas (like Nashville and Memphis) to control VD outbreaks, indicating it was a recognized problem.

- Lack of Long-Term Partners: Soldiers were separated from their wives or long-term partners for extended periods.

- Crowded Conditions & Poor Hygiene: While not directly related to transmission, crowded living conditions and general poor hygiene could exacerbate overall health issues and potentially impact vulnerability or recovery from STIs.

- Demographics: The soldier population was predominantly young, unmarried men, a demographic generally more prone to casual sexual encounters.

- Civilian Life Differences: The general civilian population included a wide range of demographics and living situations:

- Families: A large portion of the population lived in traditional family units with less frequent exposure to casual sexual partners.

- Rural vs. Urban: While urban areas would have had higher rates of STIs (due to denser populations and a more active sex trade), rural populations would have likely had much lower rates. The U.S. in 1860 was still largely rural.

- Stigma and Underreporting: Any civilian cases were highly likely to be kept private and not officially recorded due to severe social stigma. Military records, while imperfect, were systematic.

Estimating “How Many” in Civilians (Conceptual, Not Numerical):

Let’s use the 1860 U.S. Census data to give you a sense of the population numbers, but emphasize that applying the 8.2% rate directly to it is inappropriate:

- Total U.S. Population (1860): Approximately 31.4 million.

- Union States Population (1860): Approximately 19 million. (This is relevant because the 8.2% figure comes from Union soldiers).

If we were to hypothetically and incorrectly apply the 8.2% rate to the entire 1860 U.S. population, you would get: 0.082 * 31,443,321 ≈ 2,578,352 people.

And if applied to the Union states’ population: 0.082 * 19,019,969 ≈ 1,560,000 people.

Crucial Caveat: These calculated numbers (2.5 million or 1.5 million) are NOT predictions of civilian STI prevalence. They are merely arithmetic calculations based on a military statistic that cannot be directly transferred to the civilian population due to the vastly different risk factors and data collection methods.

What we can confidently say:

- STIs were a significant public health problem in the 19th century, affecting both military and civilian populations.

- The prevalence in the general civilian population was almost certainly lower than the documented rates in Union soldiers due to the specific, high-risk environment of military life.

- Specific segments of the civilian population, particularly in urban areas and those involved in the sex trade, would have experienced very high rates, potentially comparable to or even exceeding military rates. However, these would have been localized pockets within the larger population.

Therefore, while the arithmetic result of applying 8.2% to the total population gives a large number, it doesn’t represent the reality for civilians back then. The true civilian number remains unknown and likely much lower as a national average, but concentrated in certain high-risk groups.

You must be logged in to post a comment.