The Revolution Will Not be Televised…

Five years ago, all of America watched an incredibly horrific death caused by a White Police Officer using his knee to exert all his weight upon the neck of George Floyd. No one intervened. And Mr. Floyd’s life was taken. It was Horrific. A horrible way to Die. But Dying like this has a History in the Black Community of being Repeated again and again. Over and Over.

I am still Shocked at such a Horrific Death and no Big Action took Place. Where are Great Ideas that became realities helping give real Rights to Blacks?

Where I ask? Where indeed?. Where? Please unblind me? Give the Message of Real Action! Share it so We Americans do better and give true Equality to every Black Man, Woman, and Child.

Without Equality. 🇺🇸 is tied to Slavery Forever!

The Elusive Pursuit of Justice: Five Years After George Floyd, Why Systemic Civil Rights Reform Remains a Distant Goal

I. Executive Summary

This report analyzes the complex factors contributing to the perceived stagnation in civil rights reforms in America five years after the murder of George Floyd. Despite an unprecedented initial outpouring of public demand for systemic change, deeply entrenched structures, profound political polarization, organized resistance from influential groups, and the intricacies of the legal system have significantly impeded progress. While federal legislative efforts have largely stalled, and executive actions have seen notable reversals, some incremental changes have occurred at the state and local levels, particularly in police accountability and broader racial equity initiatives. The prevailing sentiment of “we got nothing” reflects the significant gap between urgent calls for transformative change and the slow, often incremental reality of addressing deeply rooted societal problems.

II. Introduction: The Unfulfilled Promise of a Turning Point

The tragic death of George Floyd in May 2020 ignited a powerful and widespread demand for civil rights changes across America, prompting millions to protest and drawing unprecedented attention to issues of racial inequality and policing. In June 2020, over eight-in-ten U.S. adults closely followed news about the demonstrations, and 52% expressed optimism that the increased focus would lead to improvements in the lives of Black people. This moment was widely seen as a potential turning point, promising significant systemic reform. Yet, five years later, a deep sense of disillusionment resonates for many, captured by the sentiment that “we got nothing, just like always” [User Query]. This perception is supported by recent polling data, which indicates that only 11% of U.S. adults believe things are better since Floyd’s killing, while a majority (54%) feel things are about the same, and a third perceive them as worse. The share of Americans who believed the increased focus improved Black lives plummeted from 52% in September 2020 to just 27% by 2025. This report seeks to understand the confluence of complex factors that have rendered meaningful, lasting change elusive, dissecting the obstacles that have frustrated the initial promise of a racial reckoning.

The rapid shift in public opinion and the immense scale of protests in 2020 created a unique window for reform. However, the subsequent decline in public optimism and support for the Black Lives Matter movement, which dropped by 15 percentage points from its June 2020 peak, indicates the inherent difficulty of translating transient public outrage into sustained political will for systemic change. This dynamic highlights a fundamental challenge in democratic processes when addressing deep-seated societal issues. The initial outpouring of grief and outrage, while powerful, was inherently difficult to maintain at such a high intensity over a prolonged period. Without rapid, tangible legislative victories, the public’s perception of a “turning point” quickly faded into disillusionment, highlighting the challenge of translating episodic public pressure into enduring institutional reform. The “nothing” sentiment, therefore, reflects the unmet expectation of immediate, transformative change rather than a complete absence of all efforts.

III. The Intricacies of Systemic Change: A Marathon, Not a Sprint

True systemic change in civil rights is inherently a protracted and non-linear process, far more akin to a marathon than a sprint. It necessitates the dismantling of deeply entrenched structures, practices, and biases that have evolved over centuries. This is not merely about enacting new legislation but fundamentally shifting cultural norms, institutional behaviors, and individual attitudes. Such transformations demand sustained effort, broad societal consensus, and a willingness to confront uncomfortable truths, often in the face of significant resistance [User Query]. The history of civil rights in the United States consistently demonstrates this pattern of “two steps forward and one step back,” where periods of significant progress are often followed by partial reversals before new advancements are made.

This historical pattern is crucial for understanding the current perceived stagnation. The civil rights movement, from its post-Civil War origins through the 20th century, has been a continuous, multifaceted struggle rather than a discrete, short-term phenomenon. For example, progress on civil rights faltered significantly in the second Grant administration and came to a definitive halt in 1876, when a political compromise led to the restoration of “home rule” in the South, undermining Reconstruction-era gains. This historical perspective suggests that the post-George Floyd period, while marked by intense public engagement, is not an isolated event but part of a much longer, cyclical battle against deeply ingrained racial structures. The resistance encountered and the incremental nature of progress are consistent with historical patterns, implying that expectations of swift, comprehensive change may be at odds with the historical reality of civil rights advancements. This helps explain why the initial momentum inevitably faces a formidable, enduring counter-force.

IV. Political Polarization and Legislative Stalemate

The deeply polarized American political landscape has proven to be a formidable barrier to comprehensive civil rights reform, particularly concerning police accountability. While there may be general agreement on the need for some reform, the specifics often become highly contentious, leading to legislative gridlock at both federal and state levels.

A. Federal Legislative Efforts: The George Floyd Justice in Policing Act

The George Floyd Justice in Policing Act (GFJPIA) emerged as the flagship federal legislative response to the calls for police accountability. This bold and comprehensive proposal aimed to create structural change by addressing systemic racism and bias in law enforcement.

Key provisions of the GFJPIA included:

* Ending Racial and Religious Profiling: Prohibiting profiling by federal, state, and local law enforcement, mandating training, and requiring data collection on investigatory activities.

* Banning Chokeholds and No-Knock Warrants: Federally banning chokeholds and carotid holds, and incentivizing states to adopt similar prohibitions. It also banned no-knock warrants in federal drug cases and conditioned funding for state and local governments on similar bans.

* Reforming Use of Force Standards: Requiring deadly force only as a last resort, mandating de-escalation techniques, and changing the use-of-force standard from “reasonable” to “necessary”.

* Limiting Military Equipment: Restricting the transfer of military-grade equipment to state and local law enforcement.

* Mandating Body Cameras: Requiring federal uniformed police officers to wear body cameras and encouraging state and local use of federal funds for this purpose.

* Enhancing Accountability: Eliminating qualified immunity for law enforcement, allowing civil lawsuits against officers for constitutional violations, and amending the federal criminal statute (18 U.S.C. § 242) to change the intent standard from “willfulness” to “recklessness” for police misconduct cases.

* Improving Transparency: Creating a nationwide police misconduct registry to prevent “wandering officers” (officers who move between departments after misconduct) and mandating disaggregated use-of-force data collection.

Despite passing the House of Representatives, the GFJPIA ultimately stalled in the Republican-controlled Senate and faced opposition from then-President Donald Trump. The primary point of contention that led to its failure was the provision to eliminate qualified immunity. This highlights the profound ideological divides that make comprehensive federal legislation incredibly difficult to pass. Even five years later, Congresswoman Ayanna Pressley continues to reintroduce key components of this reform agenda, including the “People’s Justice Guarantee” (a comprehensive decarceration framework), the “Ending Qualified Immunity Act” (co-introduced with Senator Markey), and the “Andrew Kearse Accountability for Denial of Medical Care Act” (co-introduced with Senator Warren), which would hold officers criminally liable for denying medical assistance to people in custody. These efforts underscore the ongoing, yet challenging, pursuit of federal reform.

The George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, despite its broad scope, failed due to the specific issue of qualified immunity. This indicates that even when there is general consensus on the need for reform, specific, high-impact legal doctrines become intractable political battlegrounds, effectively derailing comprehensive federal action. The legislative process’s susceptibility to single-issue stalemates is a critical barrier. This disproportionate power of one issue to derail an entire package of reforms contributes significantly to the feeling of “nothing” being achieved, despite widespread agreement on other aspects of police accountability.

Table: Key Provisions and Status of Major Federal Police Reform Legislation (2020-2025)

| Legislation Name | Key Provisions | Sponsor/Party | Current Status |

|—|—|—|—|

| George Floyd Justice in Policing Act (GFJPIA) | Prohibits racial profiling, bans chokeholds/no-knock warrants, reforms use-of-force, eliminates qualified immunity, creates misconduct registry. | Democrats | Passed House, Stalled in Senate |

| Ending Qualified Immunity Act | Eliminates the doctrine of qualified immunity, allowing civil lawsuits against officials for rights violations. | Rep. Pressley, Sen. Markey (D-MA) | Reintroduced, referred to committee |

| Andrew Kearse Accountability for Denial of Medical Care Act | Holds law enforcement criminally liable for failing to obtain medical assistance for people in custody. | Rep. Pressley, Sen. Warren (D-MA) | Reintroduced, referred to committee |

| Qualified Immunity Act of 2025 (S.122) | Provides statutory authority for qualified immunity, shielding officers unless constitutional right was not clearly established. | Sen. Banks (R-IN) | Introduced in Senate, referred to Committee |

B. Executive Actions: Shifting Federal Stances on Police Accountability

Federal executive actions have also reflected the volatile political landscape, leading to significant policy shifts that impact police accountability. During the Biden administration, the Department of Justice (DOJ) aggressively pursued “pattern or practice” investigations and entered into consent decrees with police departments found to have engaged in civil rights violations, such as in Louisville and Minneapolis. These consent decrees were designed as court-enforced improvement plans, covering policies, training, data practices, and oversight, to ensure systemic reforms.

However, a recent Executive Order (EO) signed by former President Donald Trump on April 28, 2025, titled “Strengthening and Unleashing American Law Enforcement to Pursue Criminals and Protect Innocent Citizens,” signals a dramatic reversal of these efforts. This EO aims to:

* Empower Militarized Policing: Promote “hyper-militarized policing” and increase the provision of excess military and national security assets to local law enforcement.

* Shield Officers from Accountability: Indemnify officers accused of violations, paying for their legal representation, and “strengthen and expand legal protections” for law enforcement.

* Dismantle Oversight: Direct the Attorney General to review, modify, or rescind ongoing federal consent decrees and reform agreements, effectively “dismantling the federal government’s framework for holding state and local police accountable”. This has already led to the dismissal of proposed consent decrees in Minneapolis and Louisville and the retraction of findings of constitutional violations in other departments.

* Target DEI Initiatives: Prioritize prosecution of state and local officials who “unlawfully engage in discrimination or civil-rights violations under the guise of ‘diversity, equity, and inclusion’ initiatives”. This is viewed by critics as a “scare tactic” to criminalize police accountability measures.

* Undermine Transparency: The EO has also led to the national database for law enforcement misconduct going offline.

This stark shift in federal executive policy demonstrates how fragile police accountability efforts can be when they lack enduring legislative backing, making them vulnerable to political changes at the highest level. The contrast between the Biden administration’s use of consent decrees and the Trump administration’s explicit reversal and dismantling of these mechanisms reveals a significant “pendulum swing” in federal policy. The Trump EO’s threats against DEI initiatives and local officials go beyond merely halting progress; they actively discourage future reform efforts at the state and local levels. This dynamic creates immense uncertainty and a “chilling effect” on police reform efforts. Local and state governments, facing potential federal prosecution or loss of resources, may become hesitant to pursue accountability measures or alternative policing models, even if they desire to. This undermines the stability and long-term viability of reform initiatives, contributing to the overall sense of stagnation and the perception that any gains can be easily reversed.

C. State-Level Legislative Landscape: Progress and Pushback

In the absence of comprehensive federal legislation, many police reform and accountability advocates have shifted their focus to the state and local levels, leading to a mixed bag of progress and significant pushback. Since George Floyd’s death, over 400 police reform proposals have been introduced in 31 states. As of 2022, at least 25 states have enacted legislation limiting police conduct, such as neck restraints and excessive force, and some have created new statutory duties for officers to report or intervene in rights violations. Additionally, 14 states have passed laws regulating no-knock warrants, and over 30 states have enacted bills concerning police certification and decertification.

Examples of State Progress:

* Illinois SAFE-T Act (2021): This comprehensive act mandates substantial police reform, including expanded officer training on crisis intervention, de-escalation, and implicit bias; expanded use of body-worn cameras; prohibition of police access to military equipment; and the establishment of a statewide decertification process for officers. It also empowers the Attorney General to investigate patterns of rights deprivation and bans the destruction of police misconduct records.

* New Mexico (2021 NM H 4): This law notably removed qualified immunity for police officers who violate a person’s civil rights. New Mexico is one of four states, alongside Colorado, Montana, and Nevada, that have completely banned qualified immunity as a defense in state court.

* Colorado: Enacted legislation in June 2020 banning chokeholds, limiting tear gas use, removing qualified immunity, and mandating body cameras by July 2023.

* California: Prohibited carotid restraints/chokeholds and limited the use of kinetic energy projectiles and chemical agents.

* Connecticut: Mandated that all officers intervene when witnessing excessive or illegal force.

Examples of State Pushback:

Despite these efforts, state-level initiatives are often met with significant political resistance and can be undermined. For instance, while the city of Memphis, Tennessee, enacted laws to enhance police accountability (e.g., limiting pretextual traffic stops in honor of Tyre Nichols), Tennessee Governor Bill Lee signed a bill blocking cities in the state from implementing some police reforms, effectively rendering the Memphis laws ineffective. This illustrates how state-level actions can directly undermine local reform initiatives, particularly in states that have enacted more “pro-policing” legislation.

This creates a highly fragmented and uneven landscape of civil rights reform across the U.S. While some states and localities have made substantial strides in police accountability, others have actively resisted or even reversed progress. This “patchwork” approach means that the impact of reforms is highly localized, leading to disparate outcomes for citizens depending on their geographic location. It underscores the limitations of relying solely on state-level action for nationwide systemic change and highlights the ongoing political battles that can undermine local progress. The feeling of “nothing” might be particularly acute for those in jurisdictions where such reversals occur.

V. Entrenched Resistance to Reform

Significant resistance to civil rights reform, particularly in policing, emanates from various well-organized and influential quarters.

A. The Influence of Police Unions and Lobbying

Police unions are a powerful force advocating strongly against measures they perceive as undermining officer safety or authority [User Query]. They exert considerable influence in Congress through campaign contributions, endorsements, and lobbying efforts, historically succeeding in stymieing reform legislation.

A key mechanism of their resistance lies in collective bargaining agreements (CBAs), which often provide procedural protections for officers accused of misconduct. These protections, such as those allowing officers to delay answers to investigators or limiting public access to disciplinary files, can effectively insulate officers from discipline and accountability. Critics argue that these contractual provisions, sometimes enshrined in “Law Enforcement Officer Bills of Rights” at the state level, create “further layers of insulation from discipline,” frustrating well-meaning legislative reforms. This demonstrates a powerful, organized counter-force that can resist change even when public sentiment is aligned with reform, highlighting the deep structural barriers within law enforcement itself. This institutionalized barrier within the legal and contractual frameworks governing police employment means that resistance is not merely political opposition; it is deeply embedded and can effectively nullify or weaken legislative reforms by making accountability difficult to enforce, even when laws are passed.

B. Conservative Opposition and Counter-Narratives

Beyond police unions, broader conservative movements and media outlets have actively resisted civil rights reforms, often by shaping public narratives and advocating for “tough on crime” policies.

Arguments against police reform often contend that existing laws and policing methods are adequate or that reforms would lead to increased crime, sometimes linking reform efforts to “anti-police sentiment” and “defunding the police” rhetoric. This narrative has been used to argue that police departments struggle to keep staff and that budget cuts have “devastating consequences on the safety of our officers and communities”.

There has also been a concerted effort to dismantle Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) initiatives, which are often cast as “managerialist left-wing race and gender ideology” or as “anti-white racism”. Conservative groups, including the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025, propose gutting civil rights enforcement, eliminating administrative tools like consent decrees, and banning funding for “critical race theory,” effectively weaponizing civil rights laws to target, rather than protect, vulnerable communities. These efforts aim to “rebrand” civil rights to focus on “colorblind enforcement,” which critics argue erases the reality of historical and ongoing discrimination. This signifies a more profound and dangerous form of resistance. It’s not just about opposing specific reforms but about fundamentally reshaping the legal and public understanding of civil rights, potentially undermining the very legal and conceptual foundations upon which future reform efforts would be built. This ideological battle creates a hostile environment for any initiative perceived as promoting racial equity, leading to a broader chilling effect and contributing to the feeling of regression rather than progress.

VI. The Legal Framework: Qualified Immunity and Judicial Hurdles

The legal system itself, built on precedent, can be slow and resistant to change, particularly concerning doctrines like qualified immunity.

A. Understanding Qualified Immunity: Doctrine and Debates

Qualified immunity (QI) is a judicial doctrine that shields state and local government officials, including police officers, from civil liability in lawsuits alleging constitutional rights violations. Officials are immune from damages unless their conduct violates “clearly established federal law of which a reasonable person would have known”. This standard typically requires a plaintiff to identify controlling precedent where the specific conduct at issue has been previously deemed unlawful, often demanding an “almost identical case”.

Critics argue that QI effectively shields officers from accountability, making it incredibly difficult for victims of misconduct to obtain relief and “get their day in court”. Proponents, however, contend that it is necessary for officers to perform their duties without fear of frivolous lawsuits, allowing them to make split-second decisions in dangerous circumstances. The definition of qualified immunity hinges on “clearly established law,” which “must not be defined at a high level of abstraction” and usually requires “controlling precedent” that fits the “specific facts of a case”. This means that if a specific egregious action has not been previously ruled unconstitutional in an almost identical scenario, an officer might still receive immunity, even if the conduct is objectively wrong. This creates a “catch-22” for plaintiffs: new forms of misconduct, or misconduct in slightly different factual contexts, may be protected simply because no prior case has “clearly established” their unconstitutionality. This judicial interpretation effectively grants immunity for novel abuses, making it extremely difficult to set new precedents for accountability, thereby reinforcing the perception that officers operate with impunity.

B. Judicial Interpretations and Legislative Attempts at Reform

The Supreme Court has consistently refused to hear cases challenging its qualified immunity holdings, with only Justice Clarence Thomas favoring its abolition. This judicial reluctance places the burden of reform squarely on legislative action. Federal legislative attempts, such as the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act, included provisions to eliminate qualified immunity, but these efforts stalled in Congress due to partisan divides. Senator Jim Banks’s “Qualified Immunity Act of 2025” (S.122) aims to codify qualified immunity into statutory law, further entrenching the doctrine.

In response to federal inaction, there was a concerted effort to enact state-level legislation to limit or ban qualified immunity. Four states—Colorado, Montana, Nevada, and New Mexico—have completely banned police officers from using qualified immunity as a defense in state court. Additionally, six states, plus New York City, have either limited or banned legal immunity for police officers facing civil rights lawsuits since George Floyd’s murder.

While the Supreme Court generally upholds QI, Taylor v. Riojas (2020) was a rare instance where the Court rejected QI claims, holding that immunity is unavailable for conduct so “shocking that it offends the Eighth Amendment on its face,” even if the specific behavior had not been previously established as wrong. Similarly, a January 2024 ruling by the Atlanta-based 11th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals denied qualified immunity to a jail intake officer in a case involving an inmate’s murder. These instances, while notable, are often seen as incremental changes rather than fundamental shifts.

The Supreme Court’s consistent refusal to revisit qualified immunity means that the burden of reform is placed on Congress or states. This has pushed reform to the states, resulting in a “handful” of states limiting or banning QI. The Taylor v. Riojas case and the 11th Circuit ruling are notable but narrow exceptions, suggesting the high bar for overcoming QI remains. This creates a “patchwork” of legal accountability across the United States. Depending on the state or even the specific court, the ability to hold officers accountable for rights violations varies significantly. This inconsistency means that the promise of justice is geographically contingent, contributing to the overall feeling of systemic failure. The rare judicial exceptions, while important for individual cases, do not fundamentally alter the high bar set by QI, reinforcing its enduring nature.

Table: State-Level Qualified Immunity Reforms (Post-2020)

| State | Nature of Reform | Year Enacted | Key Provisions/Impact |

|—|—|—|—|

| Colorado | Completely Banned Qualified Immunity | 2020 | Prohibits QI defense in civil rights cases; allows lawsuits against officers |

| Montana | Completely Banned Qualified Immunity | Post-2020 | Allows individuals to sue government officials and prohibits QI as a defense |

| Nevada | Completely Banned Qualified Immunity | Post-2020 | Allows individuals to sue government officials and prohibits QI as a defense |

| New Mexico | Completely Banned Qualified Immunity | 2021 | Removed qualified immunity for police who violate a person’s civil rights |

| New York City | Limited/Banned Legal Immunity | Post-2020 | Limited or banned legal immunity for police officers facing civil rights lawsuits |

VII. The Shifting Tides of Public Opinion and Media Narratives

The initial surge of public engagement and media attention following George Floyd’s death proved difficult to sustain, allowing narratives to shift and dilute the collective will for reform.

A. Initial Outcry vs. Sustained Engagement

Immediately following George Floyd’s murder, public outrage was immense, with millions participating in demonstrations across the U.S., making them the largest protests in American history. In June 2020, 52% of U.S. adults believed the increased focus on racial inequality would lead to changes improving the lives of Black people. Most Americans (77%) also believed the attention represented a change in how people thought about these issues.

However, this level of public engagement and optimism proved challenging to maintain. By 2025, the share of Americans believing the increased focus led to improvements in Black lives dropped to just 27%. Support for the Black Lives Matter movement also declined by 15 percentage points compared to its June 2020 peak. A significant partisan divide emerged, with 66% of Republicans believing there’s too much attention on racial issues, compared to 17% of Democrats. More than half of U.S. adults (54%) now say things are about the same as before Floyd was killed, with a third saying things are worse.

The initial surge in public support was insufficient to overcome systemic inertia, as sustained engagement proved challenging. The subsequent decline in optimism and widening partisan gaps illustrates how public opinion, while powerful in moments of crisis, can wane and fragment, making long-term reform efforts difficult to sustain without consistent pressure. This highlights the challenge of public fatigue and shifting priorities. While protests can create a window of opportunity, the long, arduous process of systemic change often outlasts the public’s intense focus. This waning engagement allows political and institutional resistance to regain ground, leading to the disillusionment expressed in the user query.

B. Media Framing and the “Defund the Police” Discourse

Media attention to police accountability increased significantly after Floyd’s death, reflecting and contributing to heightened public awareness of racism in policing. However, the framing of reform efforts, particularly the “defund the police” slogan, had a significant impact on public opinion and policy support.

While many proposed reforms under the “defund the police” umbrella were popular (e.g., reallocating resources to mental health services), the phrase itself was widely viewed as detracting support. There was relatively little substantive information in local news about the policy implications of “defund the police,” allowing opponents to define it negatively. This contributed to a major backlash against the racial justice movement. Studies indicate that more positive framing led to higher policy support for police reform than negative framing, and that the issue became heavily racialized, activating negative racial stereotypes.

Media narratives played a dual role: initially amplifying calls for accountability but later contributing to a backlash, particularly around the “defund the police” slogan. The lack of nuanced media explanation for the policy allowed opponents to define it negatively, significantly impacting public support and providing political ammunition against broader reforms. This highlights the critical role of narrative control in shaping policy outcomes. A concise, easily misconstrued slogan, even if intended to represent nuanced policy, can be weaponized by opponents to alienate potential supporters and create a backlash. This highlights the critical importance of strategic communication and the vulnerability of complex policy proposals to simplistic, politicized framing, ultimately contributing to the perception of stalled progress.

VIII. Beyond Policing: Addressing Interconnected Societal Disparities

The problems underlying civil rights disparities are multifaceted and deeply intertwined, extending far beyond the scope of police conduct alone.

A. Poverty, Education, Housing, and Healthcare as Civil Rights Issues

True civil rights reform necessitates addressing deeply interconnected issues of poverty, education, housing, and healthcare, which are profoundly shaped by systemic racism. Poverty, for instance, disproportionately burdens communities of color in the U.S., limiting access to stable housing, healthy foods, safe neighborhoods, and educational and employment opportunities, perpetuating cyclical effects. These socioeconomic disparities contribute to worse health outcomes, including higher rates of mental illness, chronic disease, and lower life expectancy for impoverished communities.

The report emphasizes that civil rights disparities extend far beyond police conduct, deeply intertwined with socioeconomic factors like poverty, education, housing, and healthcare. This implies that police reform alone, even if successful, addresses only a symptom, not the underlying disease. The feeling of “nothing” may stem from the fact that even if police reform were to achieve some success, the fundamental, deeply rooted disparities in other societal sectors remain largely unaddressed. This highlights a critical challenge: comprehensive civil rights progress requires a holistic approach that tackles the social determinants of health and well-being, which are far more complex and resource-intensive than single-issue legislative efforts.

B. Federal and State Initiatives for Racial Equity

Recognizing the broader scope of racial inequality, the Biden-Harris administration has pursued a “whole-of-government” approach to advancing racial equity. On his first day in office, President Biden signed Executive Order 13985, “Advancing Racial Equity and Support for Underserved Communities Through the Federal Government,” which directed federal agencies to address systemic racism and disparities.

Key Federal Initiatives include:

* Justice40 Initiative: Aims to deliver 40% of the overall benefits of certain federal investments (climate, clean energy, housing, workforce development, pollution remediation, water infrastructure) to disadvantaged communities.

* Housing: Efforts to expand affordable housing, strengthen tenant protections, and combat lending discrimination, leading to growth in Black and Latino homeownership rates.

* Education: Increased funding for K-12 schools and higher education to improve opportunity, including investments in magnet schools to reduce racial isolation and programs to increase teacher diversity.

* Healthcare: Actions to advance health equity, strengthen community-based healthcare, and address systemic inequities in social determinants of health, particularly exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic.

At the state level, many states have also taken steps to address racial equity beyond policing. A notable trend since 2020 is the increase in resolutions or statements declaring racism a public health crisis, with states like Arizona, Colorado, Hawaii, Oregon, Utah, and Washington making public commitments to address systemic racism in education, criminal justice, housing, and health systems.

Despite the focus on policing, there have been federal and state initiatives targeting broader racial equity issues. The Biden administration’s “whole-of-government” approach and initiatives like Justice40 represent a recognition of the interconnectedness of these issues. However, the impact of these initiatives may not be immediately visible or directly linked to the public’s perception of “police reform,” contributing to the feeling of stagnation. Furthermore, conservative backlash against DEI initiatives threatens these broader equity efforts. There may be a critical disconnect between the comprehensive, albeit slower, progress being made in broader racial equity initiatives (e.g., economic stability, housing, health) and the public’s perception of “civil rights reform,” which is often heavily weighted towards immediate changes in policing. This suggests that the impact of these broader equity efforts may not be immediately visible or directly attributed to the “civil rights movement” in the public consciousness, contributing to the overall sense of disillusionment.

IX. Case Studies in Local and State Reform: Incremental Progress Amidst Obstacles

Despite federal gridlock and resistance, numerous local and state jurisdictions have pursued innovative police reform and community safety initiatives, demonstrating both the potential for progress and the persistent challenges in implementation.

A. Examples of Successful Initiatives and Their Limitations

Police Funding Reallocation: Several cities have reallocated police funding to social services and community-based programs:

* New York City: In July 2020, the City Council shifted approximately $1 billion from the NYPD budget, reallocating $354 million to mental health, homelessness, and education services, and moving school safety and homeless outreach away from police. However, the NYPD budget later saw increases for overtime and technology upgrades.

* Austin, TX: In August 2020, the City Council cut its police budget by $150 million, reinvesting funds into social services, food access, violence prevention, and housing for the homeless. This was later challenged by a state law penalizing cities for decreasing police funding.

* Seattle, WA: The 2021 budget included cuts and unit transfers totaling nearly $35.6 million from the Seattle Police Department, removing police from encampment removals and tripling the Health One program (firefighters and public health professionals responding to 911 calls). $12 million was directly diverted from SPD to participatory budgeting for public health and safety. However, subsequent budgets saw increases in police funding and overtime.

* San Francisco, CA: Announced a $120 million cut from police and sheriff’s departments, redirecting funds to address disparities in the Black community, including housing, mental health, and workforce development. They also launched unarmed mobile street crisis response teams.

* Oakland, CA: Approved the Mobile Assistance Community Responders of Oakland (MACRO) pilot program, using civilian teams (EMTs, community members) for non-violent behavioral health calls.

Community-Led Public Safety Initiatives: These initiatives focus on addressing root causes of violence and providing non-police responses:

* CAHOOTS (Eugene, OR): A long-standing crisis intervention program using unarmed teams for mental distress, homelessness, and addiction calls.

* Other examples include violence intervention programs (street outreach, hospital-based), safe passage programs, and investments in affordable housing, healthcare, and education to reduce crime.

Consent Decrees: Federal consent decrees, often initiated by the Department of Justice, have been used to mandate police reforms in cities with patterns of unconstitutional practices.

* Minneapolis and Louisville: Entered into proposed DOJ consent decrees following civil rights investigations, outlining policy, training, and resource requirements. Minneapolis has also made significant progress under a state settlement agreement with the Minnesota Department of Human Rights, reporting drops in violent crime, higher officer morale, and increased police applications.

* Seattle, Newark, Albuquerque, New Orleans: Cited by the DOJ as cities that have seen success under similar court-ordered actions, with Seattle reducing serious force by 60% and Albuquerque diverting 5% of 911 calls to civilian responders.

Many city-level initiatives are described as “pilot programs” or involve initial budget reallocations that are later partially reversed or increased for police. This suggests that while local governments are willing to experiment with alternative public safety models, these initiatives often struggle with sustained funding and political commitment. The “pilot project” model can be a way to test new approaches, but it also makes them vulnerable to budget fluctuations and political shifts, preventing them from scaling up to achieve systemic impact and contributing to the perception of instability and limited lasting change.

Table: Selected City Initiatives: Police Funding Reallocation and Community Safety Programs (Post-2020)

| City | Initial Action (Year) | Services Reallocated To | Notable Outcomes/Challenges |

|—|—|—|—|

| New York City, NY | Shifted ~$1B from NYPD (2020) | Mental health, homelessness, education, school safety, homeless outreach | NYPD budget later increased by $200M for overtime/tech (2021) |

| Austin, TX | Cut $150M from police (2020) | Social services, food access, violence prevention, housing for homeless | State law penalizes cities for police budget cuts; APD budget increased (2021-22) |

| Seattle, WA | Cut ~$35.6M from SPD (2021) | Health One program, participatory budgeting for public safety, removed police from encampment removals | Subsequent budgets increased police funding and overtime (2022) |

| San Francisco, CA | Cut $120M from police/sheriff (2020) | Housing, mental health, workforce development, unarmed crisis response teams | Mayor’s 2021-22 budget increased funding to maintain police staffing |

| Oakland, CA | Approved MACRO pilot program (2021) | Civilian teams for non-violent behavioral health calls | Council voted to add new police academies and unfreeze positions (2021) |

| Portland, OR | Cut $15M from police (2020) | Disbanded school resource officers, transit police, gun violence reduction team | Council increased police budget by $5.2M (2021) for hiring/recruitment |

| Albuquerque, NM | Formed new public safety dept (2020) | Unarmed personnel for inebriation, homelessness, addiction, mental health calls | Police budget raised to ~$222M (2021) for additional officers |

| Minneapolis, MN | City Council voted to dismantle police force (2020) | Department of community safety and violence prevention | Voters rejected ballot measure (2021); police funding restored to pre-2020 levels (2022) |

B. Challenges in Implementation and Backlash

The implementation of local and state reforms has been fraught with challenges, including political resistance and legislative reversals. As seen in Tennessee, state legislatures can actively block or undermine local reform ordinances. Furthermore, the recent Trump administration’s decision to dismiss proposed federal consent decrees in Minneapolis and Louisville and retract findings of constitutional violations signals a significant federal withdrawal from police oversight, shifting the burden of accountability entirely to states and private plaintiffs. This withdrawal risks undermining progress made under these agreements and makes it harder to scale successful reforms nationally.

The cyclical nature of local reform, where initial budget cuts or reallocations are often partially reversed, points to the difficulty of sustaining radical change against entrenched institutional and political forces. This reinforces the idea that even when local communities demonstrate a will for change, higher levels of government or powerful interest groups can impede or reverse progress. The interplay of federal, state, and local authority in undermining reform is a complex dynamic. This demonstrates that even when a local community or state makes significant strides in reform, the broader federalist structure of the U.S. government allows for higher-level political actors to impede or reverse progress. This multi-layered resistance means that sustained, comprehensive reform requires alignment and commitment across federal, state, and local governments, a condition rarely met in the current polarized environment. This systemic fragmentation contributes heavily to the “we got nothing” sentiment, as local gains can be easily overshadowed or undone.

X. Conclusion: Pathways to Meaningful Change

Five years after the murder of George Floyd, the journey toward substantial civil rights change in America remains a marathon, not a sprint, marked by significant obstacles that collectively slow progress and contribute to the pervasive feeling of “nothing” being achieved. The initial outpouring of grief and demand for reform was undeniable, but the path to meaningful, lasting change has been fraught with deeply entrenched systemic issues, profound political divisions, organized resistance from powerful interest groups like police unions, the complexities of legal precedents like qualified immunity, and the shifting tides of public opinion and media narratives [User Query].

The feeling of “nothing” often stems from the gap between the urgent demand for immediate, transformative change and the slow, incremental reality of how deeply rooted societal problems are addressed. The history of civil rights in the U.S. is one of persistent struggle, often characterized by “two steps forward and one step back”. This indicates that the current moment is not merely about stalled progress but also about active attempts to roll back existing civil rights.

Long-Term Prospects and Strategic Imperatives:

* Sustained, Multi-pronged Approach: Future efforts must recognize that civil rights reform is not solely about policing but is deeply intertwined with broader issues of poverty, education, housing, and healthcare. A comprehensive, multi-pronged approach that tackles these structural determinants of well-being is essential. This includes legislative changes, judicial advocacy, and sustained community-led initiatives.

* Legislative Action: While federal efforts have stalled, continued pressure for legislation like the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act remains vital, particularly on issues like qualified immunity. State-level legislative efforts, despite their uneven impact, offer pathways for incremental progress and can serve as models for broader adoption.

* Judicial Advocacy: Continued litigation challenging doctrines like qualified immunity, even if incremental, can chip away at barriers to accountability. The rare successes in Supreme Court and Circuit Court rulings, while not overturning the doctrine, demonstrate that egregious conduct can still be challenged.

* Community-Led Solutions: Empowering communities to reimagine public safety through initiatives that reallocate resources to social services and non-police response teams can foster localized improvements and build trust. These efforts must be protected from state-level preemption and federal reversals.

* Countering Counter-Narratives: Actively challenging and reframing conservative opposition, particularly against DEI and “tough on crime” rhetoric, is crucial to maintaining public support and preventing the erosion of civil rights gains.

* Focus on Systemic Equity: The Biden administration’s “whole-of-government” approach to racial equity and initiatives like Justice40 represent important steps towards addressing underlying disparities. Sustained investment in these areas is critical for long-term, foundational change.

The imperative for the civil rights movement is not just to push for new reforms but to actively defend past gains and adopt a proactive strategy that offers a bold, multidimensional vision for equity and well-being, rather than solely reacting to challenges. This reframes the “nothing” sentiment as a call to intensify and broaden the struggle, recognizing that the fight is both defensive and offensive in an era of active attempts to roll back civil rights protections.

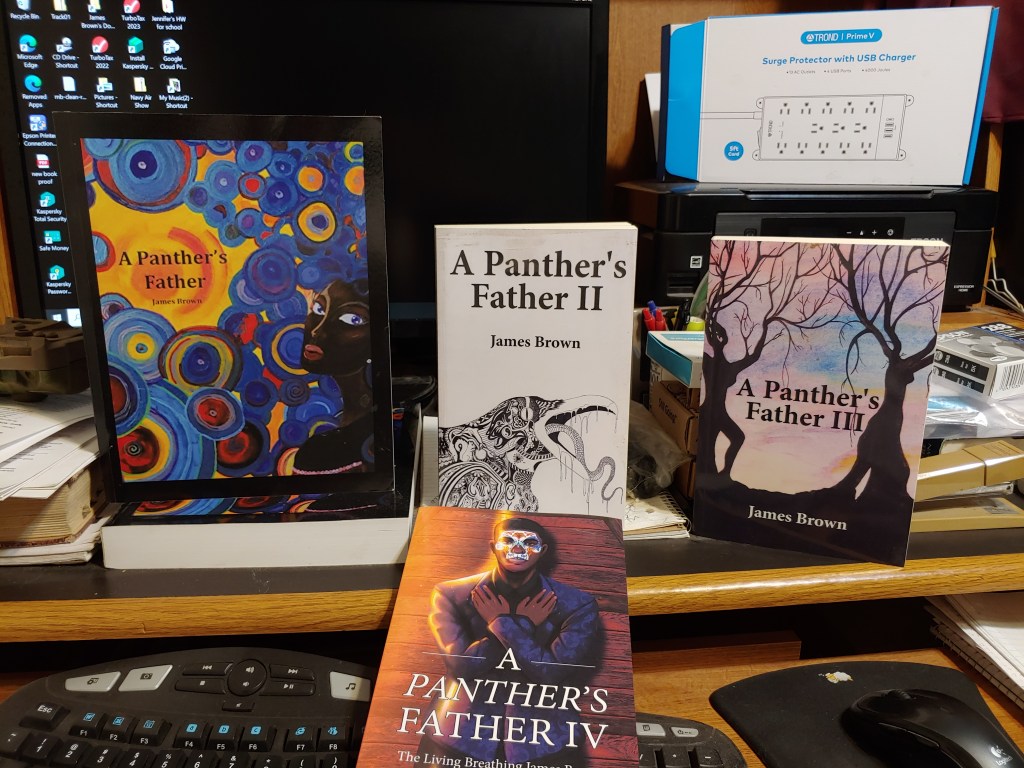

Read a Great Book-

You must be logged in to post a comment.