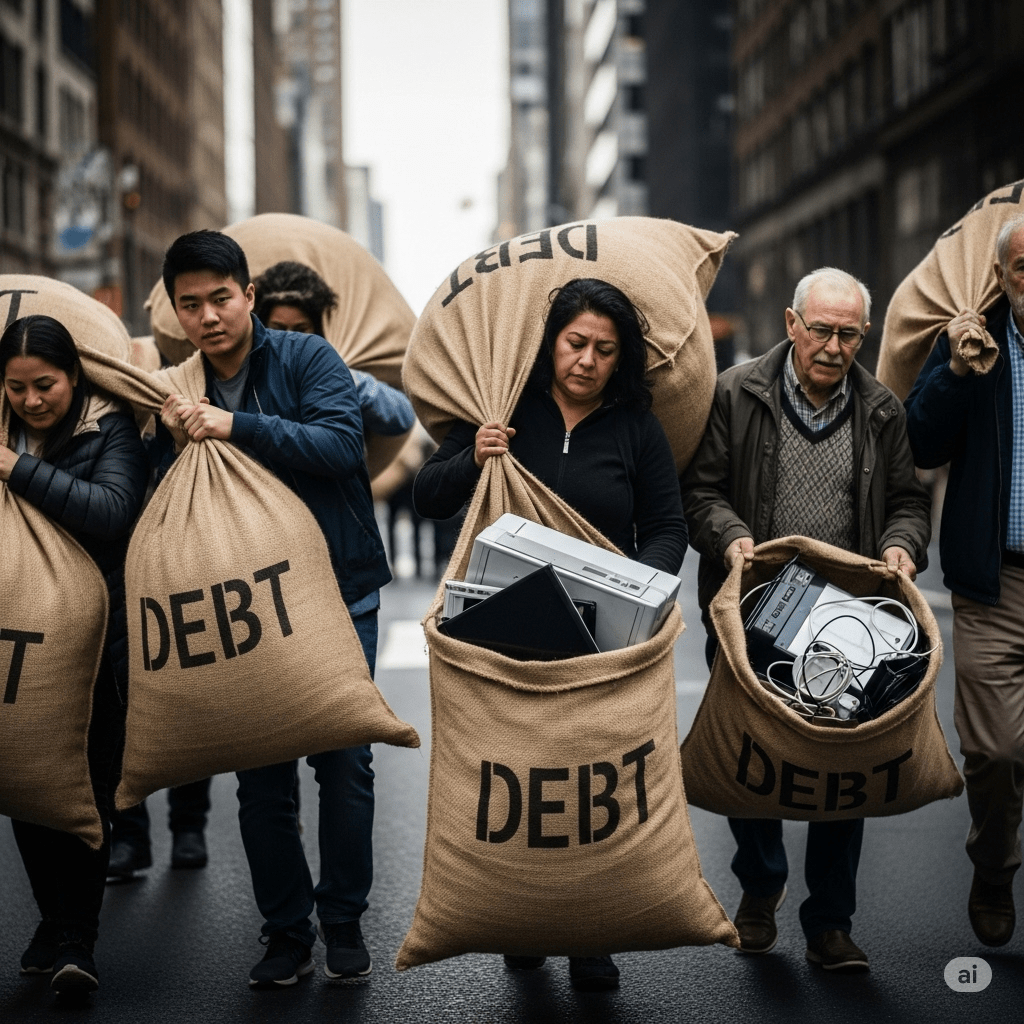

And why this could affect you very soon? So, if each American’s share of the national debt were physically represented in $1 bills, it would weigh approximately 234 pounds. Can you carry that much over your shoulder?

If a new “Big Beautiful Tax Bill” were to be passed, especially one that significantly cuts taxes without corresponding spending cuts, it would almost certainly exacerbate the problem of selling U.S. debt. Is this why DOGE was created and still doing? Make the Massive Cuts just to pass Trump’s Big Beautiful Tax Bill? You know what, something is Rotten in Denmark on all of this. The saying “Something’s rotten in the state of Denmark” is a famous line from William Shakespeare’s play Hamlet, Act 1, Scene 4. It’s spoken by Marcellus, one of the guards.

The literal meaning is a comment on the physical and moral decay within the kingdom of Denmark. However, its widely understood meaning, and how it’s used today, is:

It implies that there is a deep-seated corruption, a hidden problem, or a fundamental flaw within a system, organization, or situation that is not immediately obvious but is causing widespread unease or trouble.

It suggests that while things might appear normal on the surface, there’s a strong sense that something is seriously wrong and perhaps even morally wrong. It points to a situation where appearances are deceptive, and underlying issues are festering, potentially leading to dire consequences.

In the context of the play, it refers to the unsettling events surrounding the sudden death of King Hamlet, the hasty marriage of his widow to his brother Claudius, and the general mood of unease and foreboding that hangs over the court. Marcellus senses that these events are not just unfortunate coincidences but symptoms of a deeper, more sinister corruption within the state itself. But something is really starting to feel like Something’s Rotten in Denmark.

Doesn’t it feel that way? And too many have been receiving Death Threats to keep their Mouths Shut.

America could be eating its own tail in the near future. Kicking the Can”: It’s often politically easier to “kick the can down the road” and let future Congresses deal with the debt. The immediate consequences of high debt (like a full-blown crisis) have so far been averted, making it easier to postpone tough decisions. Let another Party Deal with it? But for sure, everybody better start working out so they can carry their fair share of America’s Debt.

But one day rapidly approaching, someone, U.S. Americans, just like you reading this are going to get stuck holding the National Debt Bag. Get Ready. And they will start SQUAWKING and run down the hallway if you Ask anyone in Congress about American National Debt. Are they ashamed?

Someone damn well needs to be A S H A M E D!

On FACE THE NATION, “America is having problems Selling its Debt”

When Senator Rand Paul, Republican from Kentucky, states that America is having difficulty selling its debt, he is referring to the challenge the U.S. government faces in attracting buyers for its Treasury securities, which are essentially IOUs the government issues to borrow money.

Here’s a breakdown of what that means and the ramifications if the U.S. truly struggled to sell its debt:

What it Means to “Sell its Debt”

The U.S. government constantly spends more money than it collects in taxes, creating a budget deficit. To cover this deficit and finance its operations (like Social Security, Medicare, defense, infrastructure, etc.), the Treasury Department issues various types of debt instruments, primarily:

- Treasury Bills (T-bills): Short-term debt, maturing in a few days to 52 weeks.

- Treasury Notes (T-notes): Medium-term debt, maturing in 2 to 10 years.

- Treasury Bonds (T-bonds): Long-term debt, maturing in 20 or 30 years.

- Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS): Bonds indexed to inflation.

These securities are sold through auctions to a wide range of investors. When the government “sells its debt,” it means these investors are buying these Treasury securities, lending money to the U.S. government.

Who buys U.S. debt?

The buyers of U.S. debt are diverse, both domestic and foreign:

- Domestic Investors:

- The Federal Reserve: The U.S. central bank, which buys Treasuries as part of its monetary policy to influence interest rates and the money supply.

- Mutual Funds and Pension Funds: They invest in safe assets to meet their long-term liabilities.

- Commercial Banks and Other Depository Institutions: They hold Treasuries for liquidity and regulatory purposes.

- State and Local Governments: They often invest surplus funds in safe Treasury securities.

- Individuals: Through savings bonds or direct purchases.

- Foreign Investors:

- Foreign Governments and Central Banks: Countries like Japan and China are significant holders of U.S. debt. They often buy Treasuries to manage their foreign currency reserves.

- Foreign Private Investors: Banks, corporations, and individuals from other countries.

When Senator Paul says America is having difficulty selling its debt, he implies that there might be a weakening demand for these Treasury securities. This could manifest in a few ways:

- Lower Demand at Auctions: Fewer bidders or lower bids at Treasury auctions, meaning the government might struggle to sell the desired amount of debt.

- Higher Interest Rates: To attract buyers, the U.S. Treasury might have to offer higher interest rates (yields) on its new debt. This makes borrowing more expensive for the government.

Senator Paul’s recent comments on Face the Nation and other outlets often revolve around concerns about the rising national debt and budget deficits, arguing that proposed spending and tax policies will “explode the debt.” He emphasizes the need for fiscal conservatism and spending cuts to address this issue.

Ramifications of the U.S. Not Being Able to Sell its Debt

If the U.S. were truly unable to sell its debt, or if it could only do so at extremely high interest rates, the consequences would be severe and far-reaching, both domestically and globally. This scenario is often referred to as a sovereign default or a debt crisis.

- Soaring Interest Rates and Increased Government Spending:

- If demand for U.S. debt drops, the Treasury would have to offer significantly higher interest rates to entice buyers.

- This would mean a much larger portion of the federal budget would go towards paying interest on the national debt, leaving less for essential services like education, healthcare, infrastructure, and defense.

- It could create a “debt spiral” where higher interest payments lead to more borrowing, leading to even higher interest rates.

- Economic Recession and Higher Unemployment:

- Higher interest rates on government debt would ripple through the entire economy, increasing borrowing costs for businesses and consumers.

- Mortgage rates, car loan rates, and credit card interest rates would all rise, stifling investment, consumer spending, and economic growth.

- Businesses would be less likely to expand or hire, leading to job losses and potentially a severe recession.

- Currency Crisis and Inflation:

- A loss of confidence in U.S. debt would likely lead to a sharp decline in the value of the U.S. dollar against other major currencies.

- This would make imports more expensive, contributing to domestic inflation, as goods and services from abroad cost more in dollar terms.

- It could also erode the dollar’s status as the world’s primary reserve currency, which has significant implications for global trade and finance.

- Financial Market Instability:

- Many financial institutions (banks, pension funds, insurance companies) hold substantial amounts of U.S. Treasuries because they are considered safe, low-risk assets.

- A decline in the value of these assets or a perceived risk of default would destabilize these institutions, potentially leading to a banking crisis or broader financial market turmoil.

- The “bank-sovereign nexus” could worsen, where struggling banks exacerbate government debt problems, and vice-versa.

- Loss of Global Influence and Trust:

- The U.S. dollar’s role as the world’s reserve currency and the perceived safety of U.S. Treasuries underpin America’s significant global economic and political influence.

- A debt crisis would severely damage the U.S.’s credibility on the international stage, making it harder to exert influence, conduct diplomacy, and maintain alliances.

- Other countries might seek alternative reserve currencies or develop new trading blocs, leading to a more fragmented global economy.

- Cuts to Public Services and Social Programs:

- In a desperate attempt to manage its finances, the government might be forced to make drastic cuts to vital public services and social safety net programs (like Social Security and Medicare), leading to widespread hardship and social unrest.

While the U.S. has never truly defaulted on its debt, threats of such a scenario (often during debt ceiling debates) have caused significant market volatility and rattled investor confidence. The full faith and credit of the U.S. government is considered a cornerstone of the global financial system, making the prospect of it being unable to sell its debt a truly alarming and unfamiliar subject to many.

Senator Rand Paul’s concerns about the U.S. having difficulty selling its debt stem from several factors, and whether it gets worse, particularly with proposed tax bills, is a critical question.

Who is “Balking” on Buying U.S. Debt?

It’s not that specific, unified groups are outright “balking” or refusing to buy U.S. debt entirely. Instead, there are shifts in demand and an increasing need for the U.S. to offer higher interest rates to attract buyers. The perception of “difficulty” comes from a combination of:

- Foreign Official Holders (like China and Japan):

- China: Has significantly reduced its holdings of U.S. Treasuries over the past decade. This isn’t necessarily a hostile act, but often a result of them diversifying their foreign exchange reserves, managing their currency stability, and sometimes in response to trade tensions or geopolitical considerations. While they remain a major holder, their share has decreased.

- Japan: Historically the largest foreign holder, Japan has also shown periods of reducing its holdings, often due to their own domestic economic conditions, monetary policy (like raising interest rates at home), or a desire to diversify.

- General Trend: The share of U.S. Treasuries held by foreign official entities has generally fallen from about 50% in 2015 to around 30% now. This means a greater reliance on domestic buyers.

- The Federal Reserve:

- During and after the COVID-19 pandemic, the Federal Reserve engaged in “quantitative easing” (QE), buying massive amounts of U.S. Treasuries to inject liquidity into the financial system and keep interest rates low.

- However, in response to high inflation, the Fed has been engaged in “quantitative tightening” (QT), actively reducing its balance sheet by allowing previously purchased Treasuries to mature without reinvesting the proceeds. This means the Fed, a once enormous buyer, is now effectively a net seller or passive participant, creating more supply for private markets to absorb.

- Domestic Private Investors (with a caveat):

- While overall demand from private investors remains robust, the composition of these buyers has shifted. More “price-sensitive” investors like hedge funds, mutual funds, and money market funds have increased their holdings. This means they are more responsive to interest rates and may demand higher yields to justify their investment.

- Conversely, demand from commercial banks has somewhat weakened, partly due to changing regulatory environments and risk management decisions.

- Households have significantly increased their direct and indirect holdings of Treasuries, absorbing a large portion of the recent increase in marketable debt.

In summary, it’s not a complete boycott, but rather a scenario where some of the historical large, less “price-sensitive” buyers are either reducing their purchases (foreign governments) or actively unwinding their positions (the Fed). This forces the U.S. Treasury to compete more aggressively for funds from private investors, often by offering higher interest rates.

Is This Going to Get Worse?

The general consensus among many economists and fiscal watchdogs is that the U.S. debt situation is on an unsustainable path, and without significant policy changes, it will get worse. Several factors contribute to this outlook:

- Structural Budget Imbalances: The U.S. faces a persistent and growing mismatch between federal spending and revenues. Major drivers of this imbalance include:

- Aging Population: Increased spending on Social Security and Medicare as the baby boomer generation retires. Government has used the monies that keep these Programs solvent by constantly nipping or chipping away at this Golden Goose and used their Monies recklessly. With no deliberate plan to replace that money. It’s fiscal malpractice at its worst.

- Rising Healthcare Costs: Healthcare expenditures continue to climb.

- Rising Interest Costs: As the national debt grows and interest rates rise (precisely the problem Senator Paul highlights), a larger portion of the budget is consumed by debt service. Interest costs are projected to be the fastest-growing “program” in the federal budget.

- Increased Debt Issuance: To cover these growing deficits, the Treasury must issue ever-larger amounts of new debt. This increased supply, coupled with potentially waning demand from traditional large buyers, naturally puts upward pressure on interest rates.

Impact of a “Big Beautiful Tax Bill” (e.g., similar to Trump’s 2017 tax cuts)

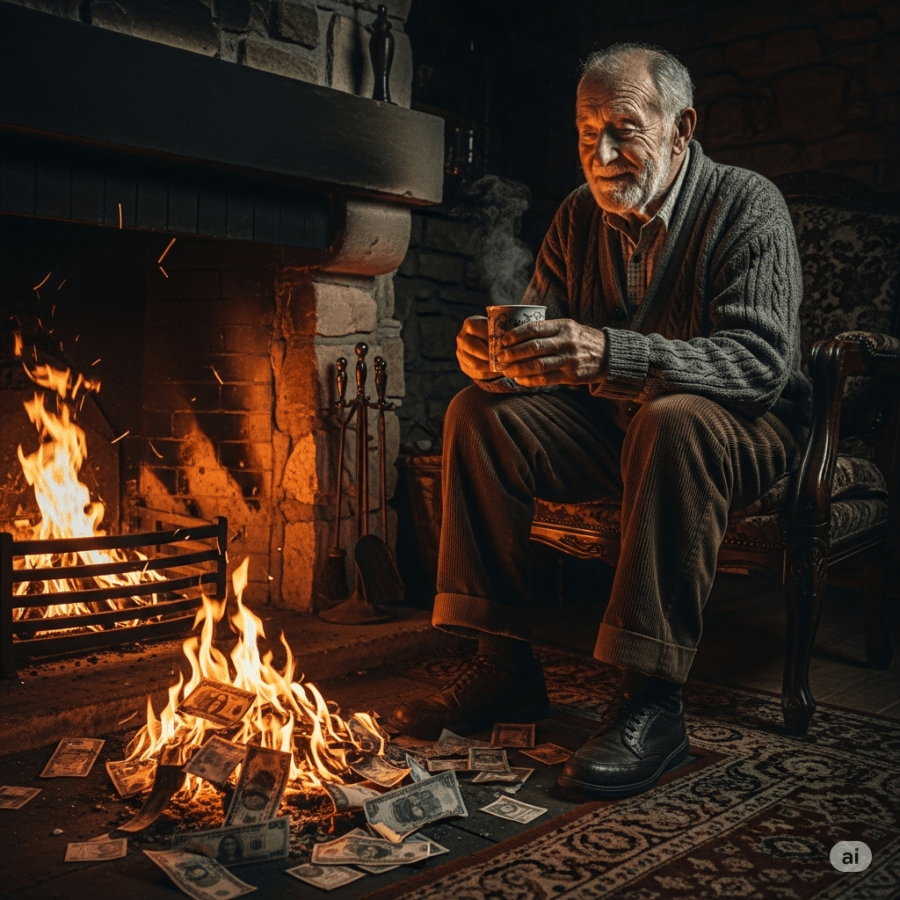

If a new “Big Beautiful Tax Bill” were to be passed, especially one that significantly cuts taxes without corresponding spending cuts, it would almost certainly exacerbate the problem of selling U.S. debt. Here’s why:

- Increased National Debt and Deficits: Tax cuts generally reduce government revenue. If these cuts are not offset by spending reductions, they directly lead to larger budget deficits and, consequently, a higher national debt. The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) is estimated to have added trillions to the national debt. Projections for extending current tax provisions show additions of trillions more.

- Example: The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget (CRFB) projects that extensions of various provisions from the TCJA could add over $37 trillion to the debt over the next 30 years, including $4.5 trillion over the next ten years.

- Greater Supply of Debt: With larger deficits, the Treasury would need to borrow even more money by issuing more bonds. This increases the supply of Treasuries in the market.

- Demand-Supply Imbalance: If the supply of U.S. debt increases significantly due to tax cuts, but the demand from buyers (domestic and foreign) doesn’t increase proportionally (or even decreases, as in the case of the Fed’s QT or China’s diversification), the government would be forced to offer even higher interest rates to attract enough buyers. This means:

- Higher Borrowing Costs: The cost of financing the national debt would surge, further straining the federal budget.

- Crowding Out Private Investment: Higher government borrowing can “crowd out” private investment by driving up interest rates for everyone, making it more expensive for businesses to borrow and expand. This can stifle economic growth in the long run.

- Increased Risk Perception: Large and rapidly growing debt can lead to concerns about the long-term fiscal health of the U.S. This could prompt credit rating agencies to downgrade U.S. debt (as has happened in the past), further reducing investor confidence and potentially driving up interest rates.

In essence, if the U.S. passes another substantial tax cut without addressing the underlying spending trajectory, it would be akin to throwing more logs on a fire that is already consuming too much oxygen. The difficulty in selling debt would likely intensify, leading to higher interest rates, increased interest payments, and potentially a greater risk to economic stability. This is a primary concern for fiscal conservatives like Senator Paul, who argue that the debt path is unsustainable and needs immediate attention through spending restraint and fiscal discipline.

While a full, catastrophic “failure to sell the debt” in the U.S. is a low-probability event due to the dollar’s global status and the U.S.’s underlying economic strength, it’s a useful thought experiment to understand the potential vulnerabilities. Here’s a chronological breakdown of what could happen if the U.S. truly struggled to sell its debt:

Stage 1: Warning Signs and Market Discomfort (What we’re seeing glimpses of now)

- Increased Interest Rates (Yields) on Treasuries: This is the most immediate and direct signal. If demand for U.S. debt softens, the Treasury has to offer higher interest rates to entice buyers. This is a common symptom when the supply of debt outpaces natural demand, or when investors perceive increased risk (even if minor).

- Failed or Under-subscribed Auctions: In this scenario, Treasury auctions (where the government sells its debt) might not attract enough bids at acceptable prices. The government would either have to accept higher rates or simply not raise as much money as needed. This would be a very public and concerning indicator.

- Increased Volatility in Bond Markets: Prices of existing U.S. Treasuries would become more volatile as investors react to the uncertainty. This creates instability for institutions that hold large amounts of these “safe” assets.

- Negative Commentary from Credit Rating Agencies: Agencies like S&P, Moody’s, and Fitch might issue warnings, or even downgrade the U.S.’s credit rating, indicating a higher perceived risk of lending to the government. This happened in 2011 with S&P.

- Weakening Dollar (Initial Stage): As concerns grow, some international investors might start to slowly shift out of dollar-denominated assets, putting downward pressure on the dollar’s exchange rate.

Stage 2: Fiscal Strain and Economic Slowdown

- Soaring Interest Payments: The government’s cost of borrowing would rise significantly. A larger and larger portion of the federal budget would be allocated to paying interest on the national debt. This would crowd out spending on other critical programs like infrastructure, education, defense, and social safety nets.

- “Crowding Out” Private Investment: Higher interest rates on government debt mean higher interest rates across the board for everyone. Mortgages become more expensive, business loans cost more, and car loans become pricier. This discourages private sector investment and consumer spending, leading to slower economic growth.

- Recessionary Pressures: The combined effect of higher borrowing costs, reduced government spending (on non-interest items), and decreased private investment would likely push the U.S. economy into a recession, leading to job losses and increased unemployment.

- Deepening Deficits (Feedback Loop): A recession reduces tax revenues (as people earn less and businesses make fewer profits) and increases some government spending (like unemployment benefits). This further widens the budget deficit, requiring even more borrowing, which exacerbates the initial problem of selling debt.

Stage 3: Crisis Escalation and Loss of Confidence

- Credit Rating Downgrades Become More Severe: Agencies would likely issue further, more significant downgrades, possibly moving U.S. debt into a “junk” status, signaling a serious risk of default.

- Flight from U.S. Assets (Widespread): This is where the true “balking” would become widespread. Both foreign and domestic investors would rapidly sell off U.S. Treasuries and other dollar-denominated assets, fearing a partial or full default, or severe devaluation.

- Plummeting Dollar and Hyperinflation Risk: With massive outflows, the U.S. dollar would likely experience a sharp and rapid depreciation against other major currencies. To manage the immense debt burden, there might be pressure on the Federal Reserve to “monetize” the debt (effectively print money to buy government bonds). This would flood the economy with dollars, leading to rampant, potentially hyperinflation.

- Financial System Instability (Banking Crisis): U.S. Treasuries are the bedrock of the global financial system. Banks, pension funds, insurance companies, and other financial institutions hold vast amounts of them. A sharp decline in the value of these assets, or a perceived risk of default, would trigger massive losses, potentially leading to widespread bank failures and a systemic financial crisis.

- Government Program Disruptions: The government would struggle to pay its bills. This could mean delays or partial payments for Social Security, Medicare, military salaries, and other essential government operations. This would cause immense social and economic distress.

Stage 4: Default or Forced Restructuring (The “Unthinkable” Scenario)

- Technical Default (Debt Ceiling Crisis on Steroids): If Congress fails to raise the debt ceiling and the Treasury runs out of “extraordinary measures” to pay its bills, the U.S. would technically default on some of its obligations. This isn’t usually due to an inability to sell debt, but rather a political inability to authorize more borrowing. However, if the market genuinely refused to buy, it would lead to a similar outcome.

- De Facto Default (Through Inflation): The government could choose to “inflate away” its debt. By allowing or encouraging very high inflation, the real value of the outstanding debt would decrease, making it easier to pay back in nominal terms. However, this devastates savings, pensions, and creates extreme economic hardship for citizens.

- Formal Debt Restructuring: In the most extreme scenario, the U.S. government might be forced to negotiate with its creditors to formally restructure its debt. This could involve reducing the principal owed, extending maturities, or cutting interest rates. This is a rare event for a developed economy and would be unprecedented for the U.S. It would signify a complete loss of trust and would cripple the U.S.’s standing in the global financial system for generations.

- Loss of Reserve Currency Status: The U.S. dollar’s role as the world’s primary reserve currency would likely end. This would have profound geopolitical implications, shifting global power dynamics and making international trade and finance much more complex for the U.S.

It’s important to reiterate that a full, catastrophic default by the U.S. is highly unlikely due to the extreme consequences and the strong incentives for policymakers to avoid it. However, the risk of it, or the perception of difficulty in selling debt, can still trigger serious economic pain by driving up borrowing costs and reducing confidence, as Senator Paul’s statements highlight. The goal of such warnings is to spur action on fiscal responsibility before more severe stages are reached.

Senator Rand Paul is certainly not alone in raising concerns about the national debt and its potential ramifications. Many economists, think tanks (like the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, the Peter G. Peterson Foundation, and the Cato Institute), and some members of Congress from both parties regularly sound the alarm.

However, it’s also true that these warnings don’t always translate into a widespread, urgent, and sustained bipartisan effort to address the debt. There are several complex political and economic reasons why many members of Congress might not be “ringing the alarm bell” as loudly or consistently as some fiscal conservatives:

- Short-Term Political Incentives vs. Long-Term Problems:

- Electoral Cycles: Politicians operate on short election cycles. Addressing the national debt often requires difficult choices like spending cuts or tax increases, which can be unpopular with voters in the short term. The benefits of fiscal responsibility (lower interest rates, stronger economy) are often diffuse and materialize years down the line, well beyond the next election.

- “Kicking the Can”: It’s often politically easier to “kick the can down the road” and let future Congresses deal with the debt. The immediate consequences of high debt (like a full-blown crisis) have so far been averted, making it easier to postpone tough decisions.

- Focus on Immediate Crises: Congress often prioritizes immediate challenges and crises (e.g., economic downturns, natural disasters, international conflicts) which can lead to increased spending without commensurate revenue.

- Partisan Gridlock and Blame Games:

- Lack of Bipartisan Consensus: Debt reduction typically requires a grand bargain involving both spending cuts (which Democrats often resist, particularly on social programs) and revenue increases (which Republicans often resist, particularly on taxes). The current highly polarized political environment makes such compromises incredibly difficult.

- Weaponizing the Debt: Both parties have historically used the national debt as a political weapon against the other side. When the opposing party is in power, the debt becomes a major talking point; when their own party holds the reins, concerns often diminish. This politicization prevents a collaborative approach to solutions.

- Debt Ceiling Debates: The debt ceiling often becomes a highly visible but politically charged battleground, where rather than focusing on long-term fiscal health, the debate devolves into brinkmanship, potentially threatening a technical default without solving the underlying spending and revenue issues.

- Economic Theories and Perceptions:

- Low Interest Rates (Historically): For a long time, interest rates were historically low, making it relatively cheap for the U.S. government to borrow. This led some to believe that deficits didn’t matter as much, or that the U.S. could simply “grow its way out of debt” through economic expansion. While interest rates have risen recently, the legacy of cheap money might still influence some thinking.

- Modern Monetary Theory (MMT): While not mainstream, some progressive voices have embraced elements of Modern Monetary Theory, which posits that a country that issues debt in its own currency can’t truly “run out of money” and can print more to finance spending, as long as it doesn’t cause excessive inflation. This view often downplays debt concerns.

- Focus on Economic Growth: Some argue that tax cuts, even if they add to the deficit in the short term, will stimulate enough economic growth in the long run to generate more tax revenue and eventually pay for themselves. This “dynamic scoring” argument is often used to justify tax cuts, though empirical evidence consistently shows tax cuts rarely fully pay for themselves.

- Public Opinion and Entitlement Programs:

- Unpopular Solutions: The biggest drivers of the national debt are entitlement programs like Social Security and Medicare, along with interest payments on the debt itself. Reforming these programs (e.g., raising the retirement age, adjusting benefits, increasing payroll taxes) is politically very unpopular.

- Lack of Public Pressure: While surveys often show Americans are concerned about the national debt, this concern rarely translates into a willingness to accept the specific, often painful, policy changes required to address it.

Will a New Tax Bill Make it Worse on Selling Our Debt?

Yes, generally speaking, if a new “Big Beautiful Tax Bill” were to be passed that significantly cuts taxes without corresponding spending cuts, it would almost certainly make it worse for selling U.S. debt and exacerbate the current challenges.

Here’s why, reinforcing points from the previous explanation:

- Increased Borrowing Needs: Reduced tax revenue means the government needs to borrow more money to fund its existing commitments. This increases the supply of U.S. Treasuries in the market.

- Upward Pressure on Interest Rates: With a larger supply of debt and potentially static or even declining demand from key buyers (like foreign governments diversifying or the Fed undergoing quantitative tightening), the U.S. Treasury would be forced to offer higher interest rates (yields) to attract enough buyers. This means the cost of borrowing goes up for the government.

- Accelerated Debt Growth: Higher interest payments on a rapidly growing debt create a negative feedback loop. More money spent on interest means less available for other programs, potentially requiring even more borrowing, pushing the debt further upward.

- Diminished Fiscal Flexibility: A higher debt burden and rising interest costs reduce the government’s flexibility to respond to future crises (recessions, pandemics, wars) because a larger share of the budget is already committed to debt service.

- Concerns About Fiscal Sustainability: A major tax cut that isn’t paid for would send a clear signal to markets and credit rating agencies that the U.S. is not serious about fiscal responsibility. This could lead to further credit downgrades and reduced confidence in the U.S.’s ability to manage its finances, making investors even more hesitant or demanding of higher returns.

While some proponents of tax cuts argue that they stimulate economic growth which eventually offsets the revenue loss, the track record of past large tax cuts (like the 2017 TCJA) suggests that they rarely “pay for themselves” entirely and often contribute significantly to rising deficits and debt.

So, while Rand Paul might be one of the loudest voices on this specific concern, the underlying issues are recognized by many, even if the political will to enact comprehensive solutions remains elusive. A new large, unfunded tax bill would likely be seen by most fiscal observers as a step in the wrong direction for the U.S. debt situation.

As of April 2025, the total U.S. national debt is approximately $36.2 trillion.

Dividing this by the current U.S. population, each American’s theoretical share of the national debt is approximately $106,000 to $106,442.

How much would that amount of debt weigh in paper money?

To calculate this, we need to know the weight of a single U.S. banknote. All U.S. banknotes, regardless of denomination, weigh approximately 1 gram. There are 454 grams in a pound.

Let’s use the average of $106,221 per American for this calculation.

- Number of $1 bills: If this entire amount were in $1 bills, you’d have 106,221 bills.

- Weight in grams: 106,221 bills×1 gram/bill=106,221 grams

- Weight in pounds: 106,221 grams/454 grams/pound≈234 pounds

So, if each American’s share of the national debt were physically represented in $1 bills, it would weigh approximately 234 pounds.

Imagine trying to carry that around! It’s a striking way to visualize the immense scale of the U.S. national debt.

You must be logged in to post a comment.