The thunder of hooves, the dust cloud behind a lone rider, the urgent dispatch carried across vast, untamed wilderness – this is the enduring image of the Pony Express. It’s an icon of American grit and ingenuity, a symbol of communication pushed to its physical limits. What often surprises many, however, is just how fleeting this legendary service actually was.

Born out of a desperate need in the spring of 1860, the Pony Express emerged at a pivotal moment in American history. With California rapidly growing after the gold rush and tensions escalating towards the Civil War, the existing mail routes were painfully slow, often taking weeks or even months for a letter to travel between the East and the West Coast. The vision was audacious: bridge the 2,000-mile gap between St. Joseph, Missouri, and Sacramento, California, in a mere ten days, carrying only critical mail.

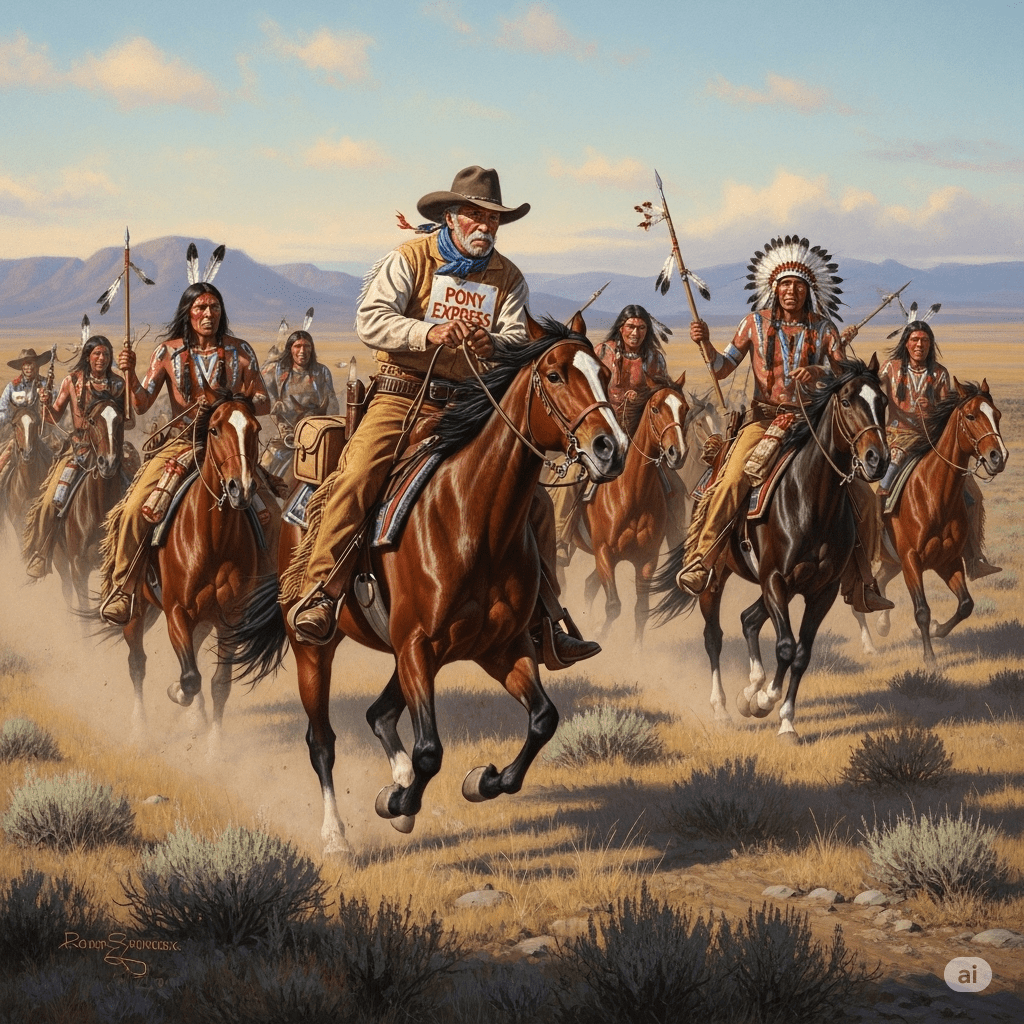

The operation was a marvel of organization and human endurance. Young, lightweight riders, often barely out of their teens, would mount swift horses and gallop across prairies, deserts, and mountains. They rode in shifts, exchanging their mochila (a special saddle cover with mail pouches) at relay stations spaced roughly every 10 to 15 miles. Fresh horses waited at each station, allowing the riders to maintain a blistering pace. Danger was constant: harsh weather, treacherous terrain, hostile encounters, and sheer exhaustion were daily companions. Yet, they delivered. News of Abraham Lincoln’s election, for instance, reached California in just 7 days and 17 hours, a feat unimaginable before their service.

For 18 intense months, the Pony Express was the fastest link between the two halves of a rapidly expanding nation. It proved definitively that rapid, reliable communication across the vast North American continent was possible. It captured the imagination of a country hungry for connection and progress, showcasing the spirit of frontier enterprise.

But just as quickly as it galloped into history, it galloped out. On October 24, 1861, the transcontinental telegraph line was completed, connecting Omaha to Sacramento. Messages that once took days could now be sent in mere minutes. The efficiency and sheer speed of the telegraph instantly rendered the brave riders and their weary horses obsolete. The last Pony Express run effectively ended within days of the telegraph’s completion.

Though its commercial lifespan was astonishingly brief, the impact of the Pony Express resonated far beyond its physical existence. It laid important groundwork for future transcontinental communication, proved the viability of routes, and more profoundly, it forged an indelible mark on the American psyche. It became a powerful testament to daring, determination, and the relentless pursuit of progress, solidifying its place not just as a historical footnote, but as an iconic, thrilling chapter in the story of the American West.

I added more fun reading?

The thundering hooves of a lone rider, silhouetted against a vast, untamed landscape, are the enduring image of the Pony Express. It’s an icon of American grit, a romanticized symbol of communication pushed to its physical limits. Yet, what often surprises many is just how fleeting this legendary service actually was, and precisely who could afford to harness its incredible speed.

Born out of a desperate need in the spring of 1860, the Pony Express emerged at a pivotal moment. With California rapidly growing after the gold rush and tensions escalating towards the Civil War, existing mail routes were agonizingly slow, often taking weeks or even months for a letter to travel between the East and the West Coast. The vision was audacious: bridge the 2,000-mile gap between St. Joseph, Missouri, and Sacramento, California, in a mere ten days, carrying only the most crucial dispatches.

The operation was a marvel of organization and human endurance. Young, lightweight riders, often barely out of their teens, would mount swift horses and gallop across prairies, deserts, and mountains. They rode in shifts, exchanging their mochila (a special saddle cover with mail pouches) at relay stations spaced roughly every 10 to 15 miles. Fresh horses waited, allowing the riders to maintain a blistering pace. Danger was a constant companion: harsh weather, treacherous terrain, encounters with hostile Native American tribes, and sheer exhaustion were daily realities. Yet, they delivered.

But this unparalleled speed came at an extraordinary price, one that immediately defined “critical mail.” At its inception, sending a mere half-ounce letter by Pony Express cost an astounding $5. To put that into perspective, this sum was equivalent to roughly $130 to $180 in today’s money and was 250 times the cost of normal mail. The average person simply couldn’t afford it.

So, who were the customers? This exorbitant fee ensured that the Pony Express was reserved exclusively for time-sensitive, high-stakes communication. “Critical mail” wasn’t personal letters from distant relatives; it was:

- Urgent business correspondence: Banks, merchants, and investors on both coasts needed rapid updates on market fluctuations, commodity prices, and financial transactions.

- Government dispatches: Especially as the Civil War loomed, official military communications, orders, and reports were paramount. News of Abraham Lincoln’s election and inauguration, for instance, were among the most eagerly awaited and costly Pony Express deliveries.

- Newspaper reports: Major newspapers in New York, Boston, and San Francisco relied on the Pony Express to get breaking news from their correspondents across the continent, often printing their reports on tissue-thin paper to minimize weight and thus cost.

- Valuable international documents: Critical war reports from English squadrons in China, for example, occasionally found their way onto a Pony Express rider’s mochila.

Every ounce counted, literally. The mail was often transcribed onto ultra-lightweight tissue paper, and riders themselves were chosen for their small stature, ensuring the combined weight of rider, saddle, and the precious 20-pound mail pouch never exceeded strict limits.

For 18 intense months, the Pony Express was the absolute fastest link between the two halves of a rapidly expanding nation. It proved definitively that rapid, reliable communication across the vast North American continent was possible, a crucial psychological and practical bridge during a period of national fragmentation.

But just as quickly as it galloped into history, it galloped out. On October 24, 1861, the transcontinental telegraph line was completed, connecting Omaha to Sacramento. Messages that once took days could now be sent in mere minutes, transmitted almost instantaneously by electric impulse. The sheer speed and vastly lower cost of the telegraph ($1 per 10 words, compared to $1 per half-ounce for a letter) instantly rendered the brave riders and their weary horses obsolete. The last Pony Express run effectively ended within days of the telegraph’s completion.

Though its commercial lifespan was astonishingly brief and its service confined to a privileged few, the impact of the Pony Express resonated far beyond its physical existence. It laid important groundwork for future transcontinental communication, proved the viability of routes, and more profoundly, it forged an indelible mark on the American psyche. It became a powerful testament to daring, determination, and the relentless pursuit of progress, solidifying its place not just as a historical footnote, but as an iconic, thrilling chapter in the story of the American West.

Being a Pony Express rider was a demanding and dangerous job, requiring exceptional horsemanship, courage, and stamina.

Here’s a breakdown of what a rider would do, their typical ride length, and their pay:

- What a Rider Would Do:

- Carry the Mail: The primary duty was to transport the mochila, a specially designed leather pouch containing the mail, as quickly as possible. The rider would dismount, throw the mochila over a new horse’s saddle, and remount, all in a matter of two minutes or less at relay stations.

- Maintain Speed: Riders were expected to push their horses to their limits, covering ground at a fast trot, canter, or gallop, often averaging 10 to 15 miles per hour, and sometimes up to 25 miles per hour on flat terrain.

- Navigate and Endure: They faced harsh conditions including extreme weather (scorching heat, blizzards), treacherous terrain (mountains, deserts), and the constant threat of encounters with Native American tribes or bandits. Riders often rode through the night, guided only by moonlight or lightning.

- Protect the Mail: The mail was paramount. Riders were instructed that if it came down to it, the horse and rider should perish before the mochila did. Letters were often wrapped in oil-silk to protect them from moisture. They typically carried a revolver and a water sack, keeping gear to a minimum to reduce weight.

- How Long One Rider Would Ride:

- A single rider typically covered a “division” or “stint” of about 75 to 100 miles per day.

- Within this daily stint, riders would change horses frequently, typically every 10 to 15 miles, at “swing stations” where a fresh, saddled horse would be waiting.

- At the end of their 75-100 mile run, the rider would reach a “home station,” where they would hand off the mochila to a new rider, get rest, and await their next turn.

- In emergencies, a rider might be required to take a “double shift,” riding two stages back-to-back, which could mean being in the saddle for 20 hours or more and covering distances like 200 miles or even upwards of 300 miles in extreme cases (e.g., Robert “Pony Bob” Haslam’s 380-mile ride or William “Buffalo Bill” Cody’s reported 322-mile ride when his relief rider was killed).

- His Pay:

- Pony Express riders were paid a relatively generous sum for the time, typically between $100 and $125 per month. Some riders on particularly treacherous routes might have received up to $150.

- This was considered a very good wage, especially for the young men often employed, as it was significantly higher than the average daily wage of about 75 cents for many laborers of the era.

You must be logged in to post a comment.