A Comprehensive History of Saint Nicholas of Myra: From Ancient Bishop to Global Icon

Executive Summary

This report offers a comprehensive history of Saint Nicholas of Myra, a figure whose global prominence as both a venerated Christian saint and the secular icon of Santa Claus stands in stark contrast to the scarcity of verifiable contemporary historical facts about his life. It delineates his probable existence as a 4th-century bishop in Myra, his enduring reputation for profound charity and miraculous interventions as depicted in later hagiographies, and the pivotal role of his relics in the widespread proliferation of his cult across Europe. The report critically examines the evolution of his legend, tracing its transformation through cultural adaptation into the modern Santa Claus figure, while maintaining a rigorous scholarly perspective on the historical reliability of sources.

Introduction: The Enduring Figure of Saint Nicholas of Myra

Saint Nicholas of Myra stands as one of the most widely venerated saints within both Eastern and Western Christian traditions, and is globally recognized as the foundational figure for the modern secular Santa Claus. His enduring presence in religious devotion and popular culture is undeniable, making him a subject of immense historical and cultural interest.

However, constructing a complete historical account of Saint Nicholas presents a unique challenge: there is a profound scarcity of contemporary historical documentation regarding his life. Much of what is commonly understood about him originates from hagiographies, or “Lives of Saints,” written centuries after his probable existence. These accounts inherently blend historical kernels with rich folklore and pious embellishment, making it difficult to ascertain precise biographical details. This reliance on later narratives means that “vanishingly little” is known about him with certainty from his own time.

This report aims to navigate this complex historical landscape by critically examining the available material. It seeks to differentiate between historically probable events, the influential hagiographical traditions that shaped his image, and the subsequent cultural evolution that transformed him into a global icon. By doing so, this analysis provides a nuanced and authoritative account, acknowledging the limitations of the historical record while appreciating the powerful cultural narratives that have sustained his legacy for nearly two millennia.

I. The Historical Bishop: Life and Context in Lycia

A. Birth and Early Life in Patara

Saint Nicholas is traditionally believed to have been born around 270 AD in Patara, an ancient city situated on the southern coast of Lycia, a region now part of modern-day Turkey. His parents were affluent Christians, renowned for their generosity and deep piety, and Nicholas was raised in an environment that fostered acts of kindness and compassion. Tragically, he was orphaned at a young age, inheriting a substantial fortune. Despite his considerable wealth, Nicholas chose to forgo a life of luxury, instead dedicating his inheritance to assisting the poor and needy, following the charitable example set by his parents.

Hagiographical accounts, particularly that by Michael the Archimandrite (c. 710 AD), emphasize his exceptional piety from an early age. These narratives even claim miraculous signs, such as his refusal of his mother’s breast on Fridays as an infant, a detail intended to highlight his innate holiness and ascetic tendencies. Such stories, while lacking contemporary verification, were crucial in establishing his early reputation for sanctity.

B. Election and Role as Bishop of Myra

After undertaking a pilgrimage to the Holy Land to seek spiritual growth and insight , Nicholas returned and settled in Myra (modern Demre), an ancient city in Lycia. At approximately 30 years of age, he was unexpectedly chosen as the Bishop of Myra. One popular legend recounts that he was selected as the next bishop because he was the first person to enter the local church after the previous bishop’s death, a divine sign to the city’s residents who could not agree on a successor.

As Bishop, Nicholas became widely recognized for his steadfast commitment to the Christian faith and his tireless efforts for the welfare of his community. He consistently advocated for the poor, the sick, and the marginalized. During periods of famine and drought, he was known to distribute food and essential supplies to those in need, earning him a reputation as a protector of the helpless. His leadership extended to pastoral duties, including preaching and instructing children in the faith.

C. The Diocletianic Persecution and Imprisonment

Nicholas lived during a tumultuous period for early Christianity, specifically under the reign of the Roman Emperor Diocletian, who initiated widespread persecution of Christians across the empire (c. 303-311 AD). This was a systematic effort to remove Christians from military service and Roman public life, aiming to restore traditional Roman glory.

During this intense period, Nicholas was imprisoned for his faith, suffering hardships and possibly torture. Accounts suggest he was also held under Emperor Licinius, Diocletian’s co-regent. His unwavering steadfastness in his beliefs during imprisonment further solidified his growing reputation as a courageous defender of Christianity. Physical evidence, such as a broken nose found in later reconstructions of his remains, could be consistent with the physical hardships suffered during such persecutions.

D. Release and the Christianization of the Roman Empire under Constantine

Nicholas was subsequently released from prison under the more tolerant rule of Emperor Constantine the Great, who succeeded Diocletian. Constantine’s promulgation of the Edict of Milan in 313 AD marked a pivotal moment, allowing for the public practice of Christianity throughout the Roman Empire and leading to the restoration of Christian property and positions. Bishops, including Nicholas, were even granted authority to make civil judgments.

Nicholas’s lifetime thus spanned a critical era, witnessing Christianity’s transformation from a persecuted minority religion at his birth to a legalized and ultimately favored religion by the time of his death. This period was marked by significant growth for Christianity, increasing from approximately 2 million adherents at Nicholas’s birth to 34 million by his death. He was a pastor and bishop during a time when accepting the burdens and risks of his office was paramount.

E. Death and Burial

Saint Nicholas died in Myra, the city where he served as bishop. His traditional feast day is observed on December 6 in Western Christian countries and December 19 in Eastern Christian countries.

The precise year of his death remains a point of scholarly discussion due to conflicting accounts. While many sources cite December 6, 343 AD , others suggest 346 AD , approximately 350 AD , or around 335 AD, as proposed by modern scholar Adam English. One account also mentions 295 AD for the Bishop of Myra, which appears to be an outlier or a transcription error given the broader chronological context of Nicholas’s life. This uncertainty underscores the reliance on later hagiographical traditions rather than contemporary historical records, which often lack the precision of modern biographical documentation.

Following his death, he was buried in a church in Myra, and his tomb quickly became a significant site of pilgrimage. The variability in dates and the absence of precise, verifiable contemporary documentation for Saint Nicholas highlight a crucial aspect of his enduring legacy. The historical record for Saint Nicholas is not a clear, linear biographical account based on direct evidence, but rather a sparse collection of widely accepted traditional dates and a few indirect confirmations. This suggests that much of what is commonly “known” about his life is derived from hagiographical accounts written centuries after his time, which inherently blend factual elements with pious embellishment and legendary accretions. The difficulty in pinpointing exact dates and events demonstrates that the idea and virtues embodied by Saint Nicholas became more significant and impactful than the exact historical person. His life story evolved into a malleable narrative, shaped and re-shaped by communities over time to serve various religious, moral, and cultural purposes, rather than being a rigid, fact-bound historical account. This dynamic is fundamental to understanding the enduring power of saints’ lives in pre-modern societies, where spiritual truth often held precedence over empirical accuracy.

Table: Key Chronological Events: Historical vs. Traditional Accounts

| Event | Traditional/Hagiographical Date/Period | Scholarly/Historical Assessment |

|—|—|—|

| Birth | c. 270 AD / c. 300 AD | c. 260 AD (Adam English) |

II. The Miraculous and the Legendary: Shaping the Saint’s Narrative

A. Acts of Charity: The Dowries for the Three Daughters

The most widely celebrated and influential act of charity attributed to Saint Nicholas is the legendary tale of his secret provision of dowries for three impoverished sisters. This act saved them from being forced into prostitution, a dire consequence of their family’s extreme poverty. According to tradition, Nicholas discreetly threw bags of gold coins through the family’s window on three separate occasions, with the money often described as landing in shoes or stockings left to dry by the fireplace.

He reportedly performed this act twice anonymously. On the third occasion, the anxious father, determined to identify his mysterious benefactor, caught Nicholas in the act. Nicholas then implored the father to keep his actions secret, a detail that further emphasized his humility and selfless giving. This particular tale is widely recognized as the foundational narrative for Nicholas’s enduring reputation as a benevolent gift-giver, directly linking his historical persona to the later Santa Claus figure. Modern scholar Adam English highlights this act as a “unique instance of charity” for its era, noting its distinctiveness from typical saint stories that often focused on martyrdom or overt miracles.

B. Miraculous Interventions and Patronages

Beyond the dowry story, a rich tapestry of miraculous interventions further solidified Nicholas’s saintly reputation and defined his diverse patronages.

One prominent legend recounts Nicholas’s pilgrimage to the Holy Land, during which a violent storm threatened to sink his ship. Nicholas calmly prayed, and miraculously, the winds ceased and the waves subsided, saving the vessel from shipwreck. This event solidified his enduring patronage of sailors and seafarers, who continue to venerate him as their protector.

Another widely circulated story tells of Nicholas miraculously restoring three young theologians to life after they were robbed, murdered, and their bodies concealed in a barrel by a wicked innkeeper. A variant of this legend describes him resurrecting three children who had been dismembered by a butcher and placed in a tub of brine, a gruesome detail that underscores the dramatic nature of his intercession. Nicholas is also credited with freeing a young boy named Basileos, who had been kidnapped from Myra and forced to serve as a cup-bearer for a foreign potentate. Nicholas miraculously appeared to Basileos and returned him to his family, still holding the potentate’s golden cup.

Beyond these specific miracles, Nicholas’s reputation also includes numerous accounts of his intervention to save innocent lives, such as three generals or men facing beheading, and his advocacy in courts of law on behalf of others. These compelling narratives, whether historical or legendary, were instrumental in establishing his widespread devotion and specific patronages, including children and young people , as well as merchants, bankers, pawnbrokers, and prisoners.

C. The Council of Nicaea: Examining the “Punching Arius” Legend

Traditional accounts often state that Saint Nicholas attended the First Council of Nicaea in 325 AD, a pivotal event in early Christian theology convened to address the Arian heresy. However, scholarly consensus indicates that his presence at the Council is debated, as his name appears only in some of the various lists of attending bishops, raising questions about the certainty of his attendance.

The popular and enduring legend of Nicholas physically striking or slapping the heretic Arius at the Council has “no ancient evidence whatever” to support its historicity. This story is not documented in any text prior to the late 14th century, and even then, it initially referred to Nicholas striking “a certain Arian” before evolving in later centuries to specifically name Arius himself. Furthermore, modern scholarship suggests it is unlikely that Arius, who was a presbyter and not a bishop, would have been present at the Council in a capacity that would lead to such a direct physical confrontation with a bishop. While physical altercations did occur at some church councils, there is no historical evidence of such an event involving Nicholas and Arius at Nicaea. Despite its lack of historical basis, this legend became a standard motif in Greek Orthodox tradition and is frequently depicted in icons. Its purpose was not to record a factual event but to powerfully emphasize Nicholas’s unwavering orthodoxy and his zealous defense of Christian doctrine against heresy.

The detailed narratives of Nicholas’s miracles—such as providing dowries, saving seafarers, resurrecting children or theologians, and freeing Basileos—are consistently presented as central to his identity and the widespread veneration he received. Crucially, these stories are often explicitly referred to as “legends” or “traditions” rather than verifiable historical events, particularly by modern scholarly sources. This pattern strongly suggests that the primary purpose of these hagiographical accounts was not to provide a factual biography in the modern sense, but rather to illustrate and amplify Nicholas’s virtues—generosity, compassion, divine intercession—and to inspire devotion among the faithful. Each specific legend directly correlates with and provides a narrative justification for a particular patronage (e.g., children, sailors, the poor, those in danger), thereby effectively explaining why people should pray to him for specific needs. The reported “manna” flowing from his tomb further served to legitimize and popularize his relics, offering a tangible manifestation of his sanctity and miraculous power. This analysis demonstrates how hagiography functioned as a potent tool for moral instruction and the propagation of religious cults in pre-modern societies, especially in the absence of mass media. These narratives were crafted to be memorable, emotionally resonant, and illustrative of core Christian ideals, effectively shaping collective beliefs and devotional practices far more profoundly than dry, factual accounts ever could. They highlight a pre-modern understanding of “truth” in religious narratives, where spiritual or symbolic truth often held greater significance and utility than empirical accuracy.

Table: Major Legends and Their Associated Patronages

| Legend | Description | Associated Patronage(s) |

| :— | :— | :— | | Dowries for Three Daughters | Secretly provided gold to save three impoverished sisters from prostitution. | Children, Unmarried Girls, The Poor, Pawnbrokers, Merchants | | Saving Seafarers | Calmed a violent storm at sea through prayer, saving a ship from sinking. | Sailors, Seafarers | | Resurrection of Three Theologians/Children | Miraculously restored three young men (or children) to life after they were murdered and dismembered. | Children, Young People, Students | | Saving Basileos | Freed a kidnapped boy from foreign servitude and returned him to his family. | Children, Young People | | Champion of Justice | Intervened to save innocent lives (e.g., generals from execution) and advocated in courts. | Prisoners, Lawyers, Judges, Merchants |

III. Death, Relics, and the Proliferation of His Cult

A. The “Manna of Saint Nicholas” and its Significance

After his death, Saint Nicholas’s tomb in Myra quickly became a significant and revered pilgrimage site. A remarkable phenomenon associated with his relics was the belief that a mysterious, sweet-smelling liquid, known as the “manna of St. Nicholas,” flowed from them. This “holy liquid” was highly sought after by pilgrims, bottled, and distributed as a purported cure-all salve, attracting Christian pilgrims to Myra for centuries and reinforcing his miraculous reputation. The continuous emission of this substance provided a tangible, ongoing manifestation of his sanctity and divine favor, making his tomb a powerful focal point for devotion.

B. The Translation of Relics to Bari (1087 AD)

A pivotal event in the history of Saint Nicholas’s cult was the translation of his relics. In 1087 AD, Italian sailors or merchants from the city of Bari successfully seized Nicholas’s bones from his tomb in Myra, which was then under Saracen control, and transported them to their home city in Puglia, Italy. This act was regarded as an “extraordinary event” during the Medieval period, signifying a major triumph for Bari and enhancing its religious prestige.

Two years later, in 1089, his relics were solemnly enshrined under the altar in the crypt of a newly constructed church, the Basilica di San Nicola, which the Baresi had built over the site of a former Byzantine palace. This dedication was overseen by Pope Urban II, with Norman rulers of Puglia present, underscoring the political and ecclesiastical significance of the event. The translation to Bari dramatically “greatly increased the saint’s popularity in Europe” and transformed Bari into a major pilgrimage center, leading to the widespread adoption of the designation “Saint Nicholas of Bari” over “Saint Nicholas of Myra”. Fragments of his relics have since been distributed globally, further extending his veneration.

C. Spread of Veneration and Patronages

Following the translation of his relics, devotion to Saint Nicholas proliferated extensively throughout Europe during the Middle Ages, reaching such prominence that his cult reportedly rivaled that of the Virgin Mary in many regions, as evidenced by church dedications. He became the revered patron saint of an exceptionally diverse array of groups and places, including entire nations like Russia and Greece, various charitable fraternities and guilds, and specific professions or demographics such as children, sailors, unmarried girls, merchants, pawnbrokers, and even cities like Fribourg in Switzerland and Moscow. Thousands of European churches were dedicated to him, with one built by Roman emperor Justinian I in Constantinople (modern Istanbul) as early as the 6th century.

His numerous miracles were popular subjects for medieval artists, inspiring countless artworks and liturgical plays that further disseminated his stories and virtues to a broad populace. His traditional feast day on December 6 was widely celebrated and notably featured the “Boy Bishop” ceremonies, a widespread European custom where a boy was elected bishop and symbolically reigned until Holy Innocents’ Day (December 28). This custom further integrated his figure into popular religious and social life.

The continuous emphasis on the “manna” flowing from his tomb and, more significantly, the physical translation of his relics to Bari in 1087 AD, underscore the profound importance of tangible objects, specifically relics, in medieval religious practice and the expansion of saintly cults. The “manna” provided ongoing, visible evidence of Nicholas’s sanctity and miraculous power, acting as a continuous draw for pilgrims and a source of legitimacy for his veneration. The translation to Bari, a major port city, was not merely an act of preservation but a highly strategic move that effectively repositioned his cult. It transformed a regionally venerated saint into a pan-European phenomenon by placing his most sacred physical remains in a location accessible to broader pilgrimage and trade networks, thereby establishing a new, powerful center of devotion and significantly increasing his visibility and influence within the Western Christian world. This case study vividly illustrates a broader historical phenomenon: the veneration of saints was often inextricably linked to the physical presence and accessibility of their relics. The competition for and strategic translation of relics were significant events, frequently driven by political, economic, and religious motivations. Cities and ecclesiastical powers vied for prestigious relics to enhance their status, attract pilgrims, and generate wealth. The shift in designation from “Nicholas of Myra” to “Nicholas of Bari” perfectly encapsulates how the physical location of a saint’s relics could fundamentally redefine their identity, their sphere of influence, and the trajectory of their cult’s development.

IV. From Saint to Santa: The Evolution of a Global Icon

A. The Dutch Sinterklaas Tradition

Following the Protestant Reformation, devotion to Saint Nicholas largely diminished across most of Protestant Europe. However, his legend remarkably persisted and thrived in Holland, demonstrating the deep cultural roots he had established. In the Netherlands, his figure evolved into “Sinterklaas,” a distinct Dutch variant of Saint Nicholas.

The Dutch Sinterklaas was traditionally depicted as a tall, white-bearded man, often wearing a red robe, who arrived on December 6 (Saint Nicholas Day) to deliver gifts to well-behaved children and lumps of coal to those who had misbehaved. This tradition is sometimes suggested to have fused with elements from pre-Christian pagan myths, such as the Norse god Wodan (Odin) and his flying horse, Sleipnir, although this particular connection remains a subject of scholarly debate and is not definitively proven. Regardless of its origins, the Dutch tradition provided a crucial bridge between the ancient saint and his modern manifestation.

B. The American Transformation into Santa Claus

The Sinterklaas tradition was brought to the American colonies by Dutch settlers, particularly to New Amsterdam (which later became New York City) in the 17th century. Over time, the Dutch name “Sinterklaas” was adapted by the burgeoning English-speaking majority into “Santa Claus,” marking a significant linguistic and cultural shift.

The figure underwent significant evolution through influential American literary and artistic contributions in the 19th century:

* Washington Irving (1809): In his satirical A History of New York, Irving depicted St. Nicholas as a rotund Dutchman who arrived in a flying wagon and delivered gifts by dropping them down chimneys. This portrayal began to secularize the saint, shifting his context from religious veneration to a more whimsical, domestic figure.

* Clement Clarke Moore (1823): His iconic poem, “A Visit from St. Nicholas” (more commonly known as “‘Twas the Night Before Christmas”), solidified many modern characteristics, including the image of a miniature sleigh pulled by “eight tiny reindeer”. This poem was instrumental in shaping the popular imagination of Santa Claus, giving him his iconic mode of transport and animal companions.

* Thomas Nast (post-Civil War): The celebrated cartoonist further developed the visual representation of Santa Claus, depicting him as a jolly, rotund figure and adding enduring features such as his residence at the North Pole and a toy-making workshop. Nast’s illustrations cemented Santa’s appearance and established his fantastical home, moving him further from his historical origins.

With the increasing commercialization of Christmas in the late 19th century, the tradition of gift-giving gradually shifted from Saint Nicholas Day (December 6) to Christmas Day (December 25). This move integrated the gift-giving tradition more directly into the broader Christmas holiday, further blurring the lines between the saint’s feast day and the secular celebration.

C. Modern Interpretations and Commercialization

The modern Santa Claus is a quintessential pop-cultural figure, representing a complex blend of the kindly old man legend rooted in Saint Nicholas and elements from older Nordic folktales of gift-giving or punishing magical figures. The pervasive commercialization of the Christmas holiday in the late 19th and 20th centuries profoundly shaped Santa’s image and role, transforming him into a central symbol of festive consumption.

This commercial association has led to criticism from various Christian denominations and other groups, who argue that Santa Claus now primarily symbolizes the materialist focus of contemporary gift-giving, sometimes overshadowing the spiritual or charitable origins of the tradition. Despite these critiques, the figure of Santa Claus remains globally beloved, a testament to the enduring power of the underlying themes of generosity and wonder.

The narrative clearly illustrates the evolution from the religious figure of Saint Nicholas to the secular icon of Santa Claus. This transformation involves distinct stages: the persistence of the legend in Dutch culture as Sinterklaas, its transplantation to America, and subsequent reinterpretation through literary and artistic works (Irving, Moore, Nast). Crucially, this process includes the incorporation of elements from other, sometimes pagan, traditions (e.g., Norse Odin, flying conveyances, elves). The shift of the gift-giving date from December 6 to December 25 is also a key indicator. This multi-stage development is a prime example of cultural syncretism, where the core attributes of a religious figure (generosity, gift-giving) are absorbed, reinterpreted, and fused with existing cultural narratives and practices in new contexts. The process effectively secularizes the figure, shifting the primary context of his benevolence from religious piety to a broader, often commercial, holiday celebration. The move of gift-giving to December 25 underscores the increasing dominance of Christmas as a widely celebrated cultural holiday, gradually overshadowing the saint’s original feast day and religious significance. This case study offers a compelling historical illustration of how religious figures and traditions can be profoundly reshaped by powerful cultural forces, including migration, literary imagination, artistic representation, and, significantly, commercialization. It demonstrates that the “history” of Saint Nicholas extends far beyond his ecclesiastical role, encompassing his profound and lasting impact on popular culture. He serves as a quintessential example of the dynamic interplay between sacred origins and modern, often consumer-driven, manifestations, prompting ongoing discussions about cultural authenticity and the evolving meaning of traditions.

Table: Evolution of Saint Nicholas’s Figure Across Cultures

| Period/Culture | Name/Figure | Key Characteristics | Associated Traditions/Dates |

| :— | :— | :— | :— | | 4th Century Myra | Saint Nicholas | Bishop, Generous Giver, Defender of Faith, Miracle Worker | December 6 feast day, Secret Dowries, Saving Seafarers, Imprisonment | | Medieval Europe | Saint Nicholas (of Myra/Bari) | Bishop, Patron of Children, Sailors, Merchants, Gift-Giver | December 6 feast day, Boy Bishop ceremonies, Relic veneration (especially in Bari) | | 17th Century Netherlands | Sinterklaas | Tall, white-bearded man in red robe, arrives via horse/boat, gift-giver | December 6 gift-giving, accompanied by Zwarte Piet (debated) | | 19th Century America | Santa Claus | Rotund, jolly, white-bearded man, flying sleigh with reindeer, workshop at North Pole | Shift to December 25 gift-giving, chimney entry | | Modern Era | Santa Claus / Father Christmas | Global icon of Christmas, symbol of generosity and commercial festivity | December 25 gift-giving, emphasis on consumer culture |

V. Scholarly Analysis: Distinguishing History from Hagiography

A. Overview of Primary Sources and Challenges

The primary source of our knowledge about Saint Nicholas is the hagiography attributed to Michael the Archimandrite, which was dictated around 710 AD. This places a significant historical distance—approximately 350 to 450 years—between the author and Nicholas’s probable lifetime, which is estimated between c. 260 and c. 335 AD. This considerable temporal gap presents inherent challenges for establishing the precise historical accuracy of many biographical details, as later accounts often incorporate legendary elements.

Other earlier, though briefer, sources include a work of praise (an Encomium) from around 440 AD and Stratelatis (The Soldiers) from around 400 AD, by an unknown author. While the first half of Stratelatis has a more straightforward narrative, similar to earlier martyrologies, its latter half contains hagiographical additions. Crucially, no literary works written by Nicholas himself have survived, nor are there any contemporary biographies from his lifetime. Even some of the earliest references, such as a laudatory speech by Patriarch Proclus of Constantinople from 440 AD, already incorporate subject matter that clearly belongs to the realm of legend rather than strict historical reporting. Indeed, the very existence of Saint Nicholas was questioned by prominent 20th-century scholars due to the notable lack of secure, contemporary references, often viewing him as a “shadowy quasi-historical person”.

B. Contributions of Modern Scholarship and Evidence

Despite the historical challenges posed by the nature of early sources, modern scholars, notably the Dominican monk Gerardo Cioffari and Adam English (author of The Saint Who Would Be Santa Claus: The True Life and Trials of Nicholas of Myra), have dedicated extensive research to Nicholas of Myra, arguing for his historical existence.

English’s research, based on a meticulous examination of ancient documents, suggests that Nicholas was born sometime after 260 AD and died around 335 AD. Indirect evidence supporting his existence includes the observation that the name “Nicholas” did not appear in the historical record before the 4th century, but subsequently became prevalent in the Myra area. This suggests that parents began naming their children after a significant local figure, indicating a real person whose story resonated with the community.

Archaeological and forensic evidence has also contributed to our understanding: his remains were discovered in Bari in 1953, having been translated there in 1087. Digital reconstructions of his face and head from these remains indicate he was approximately 5 feet, 4 inches tall and had a broken nose. This detail, while not proving specific legends like the “punching Arius” story, is consistent with accounts of physical hardship and possible torture during the Diocletianic persecutions, thereby adding a layer of material corroboration to the traditional narratives of his suffering for the faith.

C. The Enduring Challenge of Distinguishing Fact from Fiction

Ultimately, it remains inherently “difficult to distinguish the Nicholas of history from the Nicholas of hagiography and myth”. While some core elements of his life, such as his probable role as Bishop of Myra and his imprisonment during the Diocletianic persecution, are widely accepted as historically probable, many of the popular stories and miracles attributed to him (e.g., the famous “punching Arius” incident, specific miraculous interventions like resurrecting the dismembered children) lack contemporary historical backing and are largely products of later hagiographical development.

The enduring significance of Saint Nicholas often resides more in his symbolic role as a “wonder worker” (θαυματουργος) and a powerful figure of boundless charity and unwavering justice, rather than in the precise, verifiable details of his historical life. He is depicted not only with bags of gold but also with a whip, symbolizing his role in enforcing justice and order.

Establishing the “history” of Saint Nicholas requires more than just traditional textual analysis. Scholars like Cioffari and English actively engage with indirect forms of evidence, such as demographic naming patterns , and integrate findings from forensic science, including the digital reconstruction of his remains. This demonstrates that for historical figures from antiquity, especially those with sparse or highly embellished direct historical records, a truly complete understanding necessitates an interdisciplinary approach. Historians must critically engage with hagiography not simply as literal factual accounts, but as valuable cultural artifacts that reflect beliefs and societal values. Furthermore, they must actively integrate archaeological and even forensic evidence to piece together a more robust and nuanced understanding. The detail of Nicholas having a “broken nose” , while not proving the Arius punch, does provide physical evidence consistent with accounts of persecution and hardship, thereby adding a layer of material corroboration to the traditional narratives. This highlights the evolving methodologies in modern historical research, particularly for ancient and medieval periods where primary sources are often fragmented, biased, or non-existent in the contemporary sense. It underscores that historical understanding can be constructed through a triangulation of various forms of evidence—textual, archaeological, and scientific—even when direct contemporary accounts are absent. This comprehensive approach allows for a more nuanced and credible narrative that acknowledges both the probable historical kernel of a figure and the rich layers of cultural accretion that have shaped their enduring legacy.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of Saint Nicholas of Myra

Saint Nicholas of Myra embodies a remarkable dual legacy: he was likely a 4th-century bishop whose precise historical life remains largely obscured by the passage of time and the scarcity of contemporary records, yet whose figure has achieved unparalleled global recognition and enduring cultural significance. His core historical likelihoods, such as his role as Bishop of Myra and his survival of the Diocletianic persecutions, are augmented by the powerful virtues that defined his legendary persona: profound generosity, unwavering justice, and compassionate protection of the vulnerable.

The hagiographical narratives that emerged centuries after his death, coupled with the strategic translation of his relics to Bari, were instrumental in the extraordinary proliferation of his cult across diverse cultures and geographies, transforming him into a widely venerated saint throughout Christendom. These narratives, while not strictly historical, served a vital function in conveying moral lessons and promoting devotion, illustrating how religious “truth” in pre-modern societies was often conveyed through compelling stories rather than empirical facts. The physical presence of his relics, and the belief in their miraculous properties, further anchored his cult, providing tangible focal points for pilgrimage and veneration that significantly expanded his influence.

Ultimately, his most profound cultural impact lies in his remarkable transformation from a revered Christian saint to the beloved, secular icon of Santa Claus. This evolution, driven by cultural adaptation, literary reinterpretation, and eventual commercialization, stands as a compelling testament to the enduring power of myth, the universal appeal of selfless charity, and the dynamic process of cultural adaptation across millennia. The story of Saint Nicholas of Myra thus continues to resonate across the globe, a testament to a historical figure whose virtues transcended the limitations of documented history to become a timeless symbol of benevolence and joy.

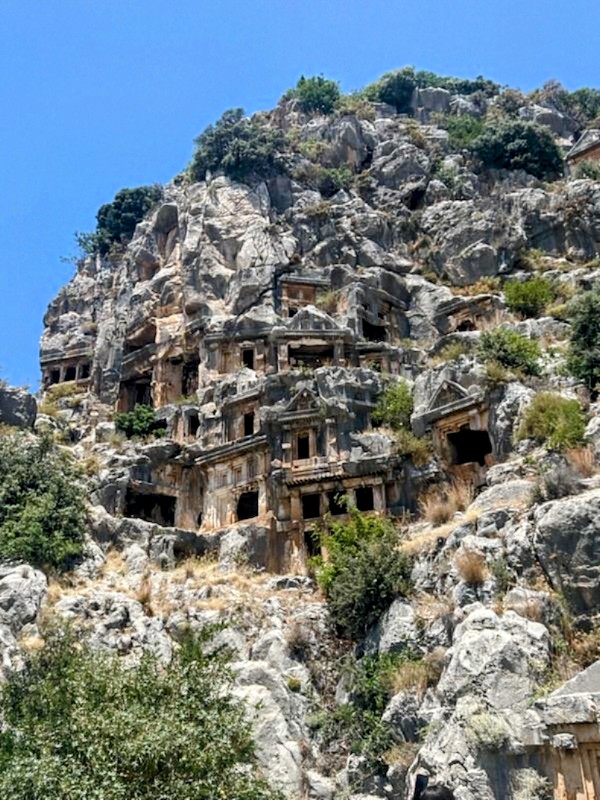

This Photo was taken not very long ago on St. Nicholas Island in Turkey

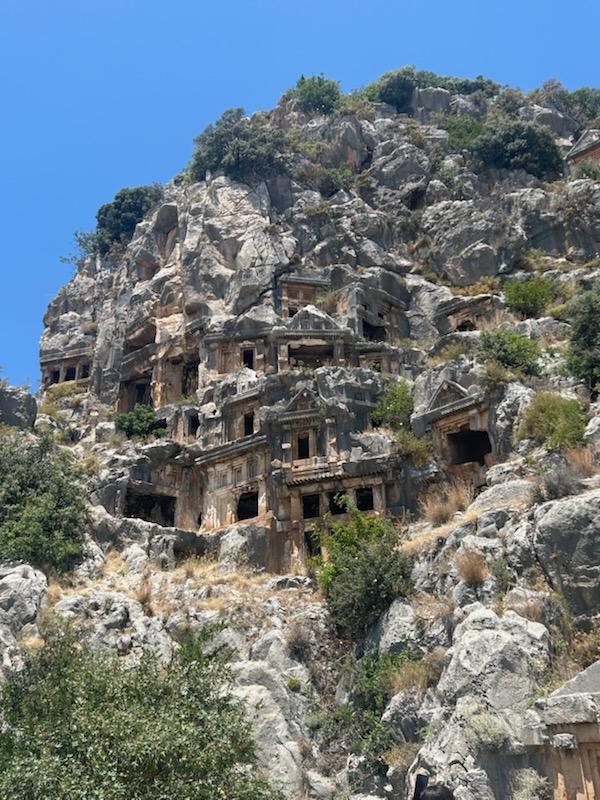

Another photo taken on St. Nicholas Island recently.

You must be logged in to post a comment.