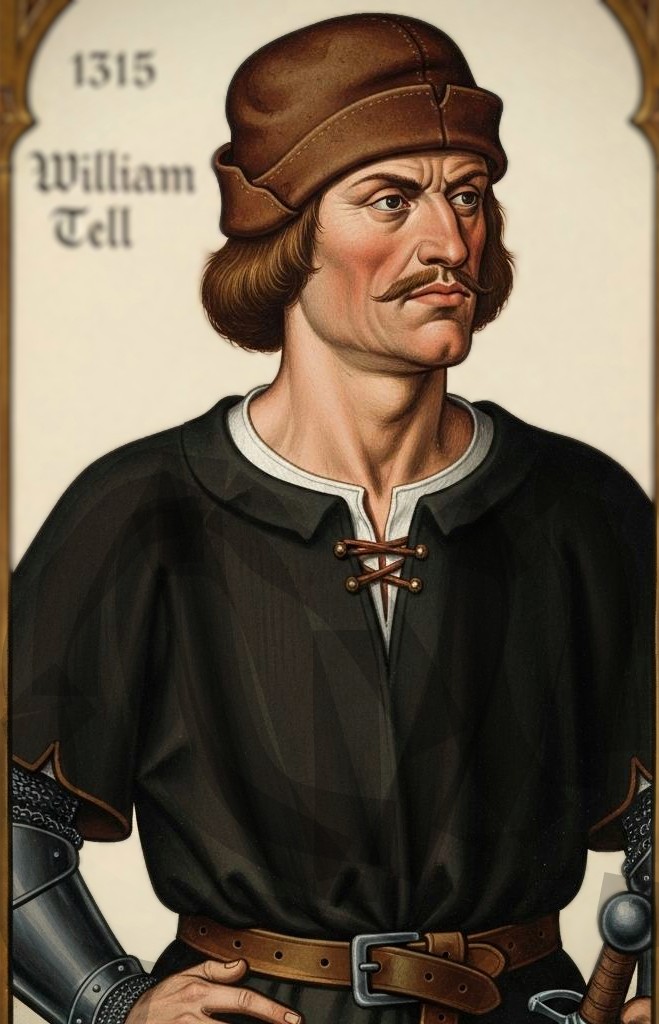

The air, a living thing, hummed with the electric tension of a world on the cusp of change. The scent of rain-soaked pine, bitter and ancient, mingled with the metallic tang of a coming storm. The year was 1315, and the very soil of the land seemed to hold its breath. William Tell, his figure etched against the looming granite of the Alps, was no stranger to such moments. His hands, gnarled and powerful, bore the callouses of a life spent in communion with the untamed mountains, as equally at home with the heft of a crossbow as they were with the patient shaping of wood and stone. He stood on the muddy bank of the Reuss, the river a churning, gray ribbon that mirrored the turmoil in his heart. The Burgenbruch, the bold rebellion that had seen castles crumble and tyrants defied, was not an old memory, but a fresh, bleeding wound in the memory of the Habsburgs. They had not forgotten the humiliation of being bested by simple mountain folk.

Now, that memory had coalesced into a storm of steel. A vast host of Austrian knights, their polished armor gleaming with a cold, unforgiving light, marched with the inexorable certainty of a flood toward the verdant valley of Schwyz. The confederates, a loose brotherhood of farmers, woodsmen, and shepherds, were the valley’s last hope. They were not a professional army, but a people bound by a shared land and a fierce love of freedom. They stood ready at the pass of Morgarten, a name that would soon be whispered in awe and terror. The land itself was their greatest ally—a narrow, treacherous track wedged between the sheer, unforgiving mountainside and the swirling, malevolent shores of Lake Ägeri.

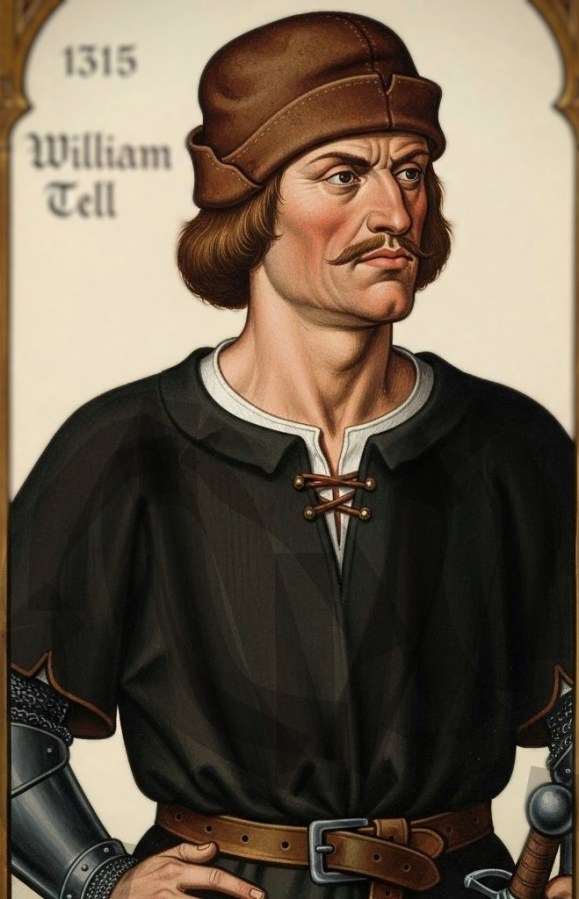

Tell was not a soldier of the grand houses, sworn to a lord and a crest. He was a man of the mountains, a craftsman of wood and a master of the hunt. His banner was not silk embroidered with a lion, but the heavy, time-worn crossbow he carried—the very same one that had, with a desperate, gut-wrenching gamble, split an apple on his son’s head. That shot had been an act of defiant theater, a desperate plea for a future free from tyranny. This, however, was different. This was war, raw and unromantic, a grim necessity born of survival.

The Austrians, bloated with the arrogance of their station and the certainty of their might, funneled themselves into the narrow pass. The ground beneath their horses’ hooves was a treacherous quagmire, the path slick with the day’s ceaseless rain and churned mud. The high-born knights, encased in the prison of their steel, found their movement hampered, their heavy lances, designed for the grand sweep of an open field, utterly useless in the suffocating confines of the pass. They were a magnificent serpent, but a serpent caught in a bottle.

High on the mountain slope, Tell was a part of a small group of Schwyzers, their faces grim and resolute. They were not schooled in the grand strategies of war, but they were men of the earth, with an intimate, almost spiritual understanding of its unforgiving nature. The signal came, not a trumpet’s call but the sharp, piercing cry of an unseen scout, a sound as ancient as the mountains themselves. And then, the world came apart. A deafening roar erupted as a cascade of stones and logs, painstakingly gathered from the forest, thundered down the slope. It was the mountain’s own angry voice.

The first volley was a cataclysm. It struck the heart of the Austrian column with the force of a divine judgment. Horses screamed in terror and agony, their magnificent bodies crushed beneath the weight of the mountain’s wrath. Men, their faces twisted in a moment of pure, uncomprehending terror, were swept away like autumn leaves. The narrow pass, a moment ago a parade ground for the proud, became a scene of chaotic carnage. Tell, his comrades beside him, unleashed their arrows and bolts from above. The range was long, a challenging distance even for a master archer, but his aim was not just impeccable—it was an extension of his will. He chose his targets with a grim, surgical precision, not by the rank or finery of their armor, but by their strategic position: a standard-bearer whose fall would sow confusion, a knight leading a hopeless charge, a horse that was blocking the path, turning a retreat into a rout.

Tell’s second arrow, the one he had once prepared for Gessler, the one meant for a tyrant’s heart, was now loosed into the melee. There was no grand, theatrical flair to its flight. It was a simple, brutal truth, a whisper of death. It found its mark in the unprotected throat of a heavily armored knight, a chink in the cold steel that was a man’s last mistake. There were no speeches, no declarations of liberty. Just the grim, practiced efficiency of a man who knew how to kill with a projectile, a skill honed by a lifetime of necessity.

The Austrians, their senses blinded by the falling rocks and their ranks bewildered by the unseen, unyielding attackers, found their formation shattering. It was no longer an army, but a panicked mob. The confederates, lighter and more agile, descended from the slopes like mountain ghosts. Their weapons were not the elegant swords of the knights but the brutal, utilitarian tools of their lives: halberds and morning stars, weapons designed not for duels but for close-quarters combat against armored foes, for finding the gaps and rending the steel.

Tell, now on the ground, fought with the primal ferocity of a trapped bear. His crossbow, slow to reload and useless in the press of bodies, was laid aside. In his hands was a heavy axe, a simple tool of the woodsman that was now a whirlwind of destruction. His strength, the same quiet power that had saved his son from the tyrant’s whim, was a force of nature. He moved with a mountain man’s grace, a fluid dance of survival, dodging the clumsy, ponderous thrusts of the knights and striking with a savage efficiency at the joints and weak points in their armor.

The battle was a massacre, a symphony of steel and screams. The land itself, the very earth and stone of the pass, seemed to have risen in a furious, elemental rebellion against the invaders. The Austrians were broken, their proud army shattered not by a more powerful force, but by the unyielding, ferocious spirit of a people who simply refused to bow.

When the last of the Habsburg knights had fled in ignominious terror or fallen in a muddy, bloody grave, Tell stood amidst the carnage. His face was a mask of mud and blood, his chest heaving with the exhaustion of a man who had stared death in the face and won. There was no triumph in his eyes, no heroic fanfare. Only a weary, grim resolve. He was no mythological hero, a figure of painted legend. He was a man who had fought for his home, for the memory of his family’s freedom, for the right to simply exist.

The tale of William Tell wasn’t just a legend of a single brave act that defied a tyrant. It was the story of a man who, in the face of absolute tyranny, chose to fight not with a storybook’s flourish but with the grim, brutal reality of a soldier on a muddy battlefield. He was a piece of the crucible of war that forged a nation, a symbol who, on that day at Morgarten, was also just a man, fighting for his life, and the life of his people, with a cold, silent fury. His name would echo through the valleys, but it was his actions, unadorned and terrible, that would grant a people their dream of a home in the mountains, safe from the storms of foreign kings.

You must be logged in to post a comment.