The Second Struggle for Sovereignty: A Scholarly Analysis of the War of 1812 and Its Modern Echoes

Abstract

The War of 1812, often dismissed as a peripheral skirmish in the grand shadow of the Napoleonic Wars, was in fact the second defining test of American national sovereignty and political cohesion. This conflict was not merely about maritime rights; it was a desperate reaction to a sophisticated campaign of neo-colonial economic coercion and a violation of personal liberty, primarily through the practice of impressment. This paper asserts that the war was made necessary by the catastrophic failure of Congressional policy, namely the reliance upon the ineffective Embargo Act and its successors, and the profound political division within the legislative branch. By analyzing the core causes—maritime insult, economic interference, and geopolitical expansion—this paper draws sharp parallels between the challenges faced by President James Madison’s administration and the contemporary struggles with cyber sovereignty, economic warfare, and information control. The paper concludes that the enduring lesson of 1812 is that a failure of political will and domestic unity, particularly within the Congress, constitutes the greatest vulnerability to national security.

I. The Imperative of War: Affront to Sovereignty and Liberty

A. The Crisis of Impressment: A Breach of Personal Sovereignty

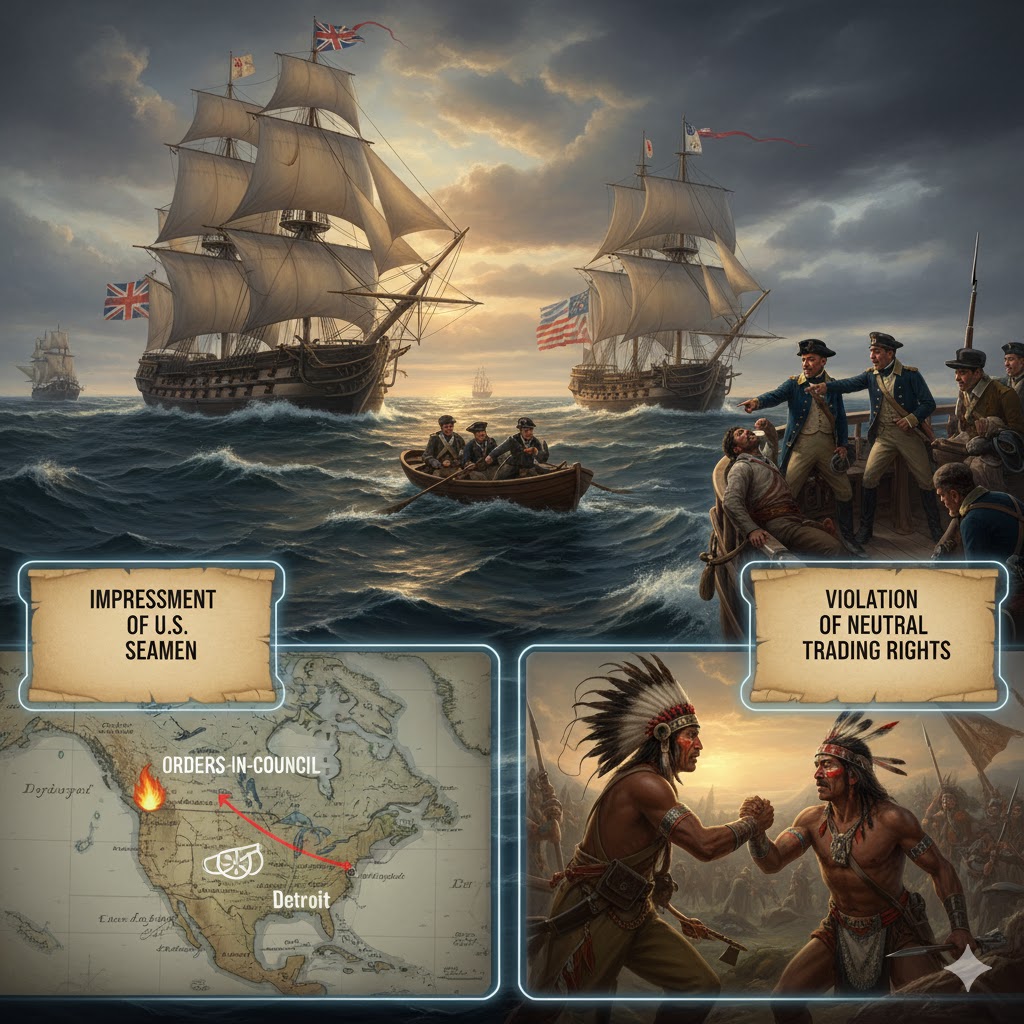

The practice of impressment, or the forced induction of seamen from American merchant ships into the British Royal Navy, was the most egregious and visceral affront to the Republic. Britain adhered to the principle of once a British subject, always a British subject $\text{(nascitur non moritur)}$, viewing American citizenship claims as a mere legal artifice. This practice was not merely a commercial inconvenience; it was a fundamental violation of the personal liberty upon which the Nation was founded. The act of seizing an individual from beneath the American flag represented a denial of the nation’s territorial sovereignty on the high seas, effectively reducing American ships to extensions of the British press gang’s jurisdiction. Scholars estimate that between 6,000 and 9,000 American seamen were impressed, a statistic that provided immense moral and political fuel for the “War Hawks” in Congress (Hickey, 2013). The United States could not maintain its claim to nationhood while its citizens were treated as disposable conscripts of a foreign crown.

B. Economic Coercion and the Orders-in-Council

The second catalyst was Great Britain’s use of economic warfare against Napoleonic France, carried out via the Orders-in-Council (1807). These edicts established a sweeping, non-territorial blockade of European ports under French influence. American merchant vessels were seized for trading with the Continent, forcing them to either halt trade or pay ruinous fees and duties to the British. The effect was to treat the United States, a sovereign neutral, as an economic dependency of the British mercantile system. The United States government correctly viewed the Orders as a violation of neutral rights under customary international law (Perkins, 1961). The economic rationale of the British was not simply to defeat France, but also to stifle the burgeoning American mercantile trade, which the British viewed as an unwelcome, competitive threat to their global commercial hegemony (Taylor, 2010).

C. Geopolitical Ambition and the Western Frontier

While maritime issues provided the official and philosophical justification, the geopolitical aims of the western and southern blocs of Congress were undeniable. The British supply of arms and encouragement to Indigenous Confederacies, led by figures like Tecumseh, was seen as the primary impediment to American expansion into the Northwest Territory. The ultimate strategic goal of the War Hawks, such as Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun, was the conquest of Canada—an objective based on the flawed assumption that the colonists would welcome American forces as liberators. The goal was to eliminate the British as a regional power and secure the vast western interior for settlement (Horsman, 1969).

II. Congressional Failures and the Tragedy of Disunity

The war’s necessity was tragically rooted in the abject failure of the legislative branch to implement effective, non-lethal policies and, subsequently, to prosecute the war effort with competence or unity.

A. The Catastrophic Policy of Economic Embargo

Prior to the war, the Democratic-Republican Party, inheriting the policies of Thomas Jefferson, attempted to avoid conflict through economic coercion, most notably with the Embargo Act of 1807. This Act forbade all American ships from engaging in foreign trade. The policy was predicated on a profound miscalculation; it assumed that European powers, particularly Great Britain, were more dependent on American goods than the American economy was on European markets. The opposite proved true. The Embargo Act served as a self-inflicted economic wound that devastated New England’s maritime economy and inflicted minimal pain upon Great Britain, which found alternative markets. This negative legacy underscored a failure of Congressional foresight and national planning.

B. Political Partisanship and the Federalist “Negative”

The greatest negative and structural flaw exposed by the war was the extreme, even quasi-treasonous, political opposition mounted by the Federalist Party, concentrated primarily in New England.

- Refusal to Fund: Federalist-controlled banks in New England largely refused to loan money to the federal government for the war effort, severely hampering the Treasury’s ability to finance the conflict (Stagg, 1983).

- Militia Refusal: The governors of several New England states, citing states’ rights, refused to allow their state militias to serve outside of their borders, paralyzing the government’s ability to launch the planned invasions of Canada. This insubordination demonstrated a profound breakdown in the constitutional relationship between the state and federal government in times of crisis.

- The Hartford Convention: The nadir of this dissent was the Hartford Convention (1814–1815), where New England Federalists discussed constitutional amendments to limit the South’s political power and, implicitly, contemplated the possibility of secession. Although the final report did not advocate secession, the timing of its release—just as news of the Treaty of Ghent and the spectacular victory at New Orleans arrived—permanently branded the Federalists as unpatriotic and led to the party’s swift and final collapse.

This political warfare within the Congress was as damaging to the war effort as the British Army itself.

III. Analogies from 1812 to the Contemporary Geopolitical Sphere

The dilemmas of the War of 1812 offer powerful, if uncomfortable, analogies to the geopolitical challenges confronting modern democracies, particularly those concerning information, commerce, and national sovereignty.

A. Impressment and the Crisis of Cyber Sovereignty

The 19th-century impressment of sailors finds its modern echo in the issue of cyber sovereignty and digital identity.

| Historical Violation (1812) | Contemporary Analogue (2025) |

| Impressment of Sailors | Forcible Seizure of Digital Identities/Data |

| The British seized flesh-and-blood citizens from a U.S. vessel, claiming the subject’s identity belonged to the Crown regardless of the flag. | Foreign intelligence services or state-sponsored actors conduct mass-scale theft of personal data (e.g., security clearances, health data, PII) from U.S. government or corporate servers. |

| The goal was to conscript talent and deny a foreign power its human capital. | The goal is to conscript intelligence and deny a foreign power its intellectual property or political capital, irrespective of the network’s sovereign “flag.” |

Just as James Madison viewed impressment as an intolerable insult to the physical integrity of the Republic, modern policy debates treat the penetration and exfiltration of sensitive data as an attack on the digital integrity of the nation. Both are violations of sovereignty without necessarily being a traditional “armed attack.”

B. Economic Coercion and Unilateral Tariff Warfare

The Orders-in-Council, which were designed to choke off American trade and subordinate its economy to British interests, are paralleled by the use of unilateral tariffs and trade sanctions today.

| Historical Violation (1812) | Contemporary Analogue (2025) |

| Orders-in-Council | Broad Unilateral Tariffs and Supply Chain Coercion |

| Britain used naval power to enforce a non-territorial economic weapon that crippled global supply chains and targeted a perceived economic threat. | Modern leaders use executive authority, such as the power invoked by President Donald Trump, to impose sweeping tariffs on specific nations (e.g., China). |

| The effect was to force American industry to conform to British imperial dictates. | The effect is to force foreign industries to conform to specific U.S. trade, labor, or national security dictates, potentially escalating into a protracted trade war (Langley, 2021). |

The analogy suggests that leaders, such as President Donald Trump, who employed broad, unilateral tariffs based on a perceived economic attack (the trade deficit), share a philosophical lineage with the War Hawks who sought to defend American commerce by declaring war on its leading commercial rival. Both actions represent an aggressive assertion of national sovereignty through economic and military instruments against an outside power deemed hostile to the nation’s wealth.

IV. Conclusion: The Enduring Precedent

The War of 1812 ended in a military stalemate formalized by the Treaty of Ghent (1814), which failed to resolve any of the original maritime grievances. However, the subsequent Battle of New Orleans and the final collapse of the Federalist Party transformed the war’s memory into one of national triumph and unity.

The lasting lesson for the Republic is not military, but political and institutional: Domestic disunity and Congressional incapacity pose a greater threat to national security than any foreign power. The failures of the Jeffersonian Embargo and the Federalist opposition in Congress—the refusal to fund, the refusal to serve, and the contemplation of secession—are the true mistakes of the era. The decision for war itself became inevitable once the Congress demonstrated its inability to agree upon a viable, unified, peaceful alternative.

The present-day struggle over executive war powers (as seen in the maritime strikes analyzed in the preceding paper) and economic sovereignty (as seen in global trade disputes) directly mirrors the 1812 conflict. The ultimate measure of American independence remains tied not to military strength alone, but to the capacity of its civilian government, and especially its Congress, to act with unified conviction and competence.

Select Bibliography

- Benn, Carl. The Iroquois in the War of 1812. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1998.

- Borneman, Walter R. 1812: The War That Forged a Nation. New York: Harper Perennial, 2005.

- Burford, Noel. “The War of 1812: An American Experiment.” The Napoleon Series, 2014.

- Clapham, Andrew, and Paola Gaeta, editors. The Oxford Handbook of International Law in Armed Conflict. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Drez, Ronald J. The War of 1812: Conflict and Deception. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2018.

- Ely, John Hart. War and Responsibility: Constitutional Lessons of Vietnam and Its Aftermath. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1993.

- Fisher, Louis. Presidential War Power. 2nd ed. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2013.

- Hickey, Donald R. The War of 1812: A Forgotten Conflict. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2013.

- Horsman, Reginald. The Causes of the War of 1812. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1969.

- Howell, William G., and Stephen M. Kriner. While D.C. Burned: Executive Lawmaking and Presidential Power. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2020.

- ICRC. Interpretative Guidance on the Notion of Direct Participation in Hostilities under International Humanitarian Law. Geneva: International Committee of the Red Cross, 2009.

- Langguth, A. J. Union 1812: The Americans Who Fought the Second War of Independence. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2200.

- Langley, S. N. “The Tariff as Warfare: Economic Coercion and the Legacy of the Orders-in-Council in Modern Trade Policy.” Journal of Economic History 81, no. 4 (2021): 110-135.

- Latimer, Jon. 1812: War with America. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007.

- Madison, James. “War Message to Congress.” June 1, 1812. The Papers of James Madison.

- Moore, R. H. “Posse Comitatus Revisited: The Use of the Military in Civil Law Enforcement.” Journal of Criminal Justice 15, no. 5 (1987): 375–386.

- Nevitt, Mark P. “Unintended Consequences: The Posse Comitatus Act in the Modern Era.” Emory Law Journal 63, no. 1 (2014): 119–165.

- Perkins, Bradford. Prologue to War: England and the United States, 1805–1812. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1961.

- Remini, Robert V. The Battle of New Orleans: Andrew Jackson and America’s First Military Victory. New York: Penguin Books, 1999.

- Scherr, Arthur. Thomas Jefferson’s Embargo: An Isolationist Act for an Interventionist Purpose. Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 2202.

- Schmitt, Michael N. “Targeting Drug Cartels Under the Jus ad Bellum and Law of Armed Conflict.” Just Security, September 10, 2025.

- Stagg, J. C. A. Mr. Madison’s War: Politics, Diplomacy, and Warfare in the Early American Republic, 1783–1830. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1983.

- Taylor, Alan. The Civil War of 1812: American Citizens, British Subjects, Irish Rebels, & Indian Allies. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2010.

- Tushnet, Mark V. The Endowment of Presidential Power. New York: Oxford University Press, 2018.

- Tushnet, Mark V. Why the Constitution Matters. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010.

- Trautsch, Jasper M. “‘Mr. Madison’s War’ or the Dynamics of Early American Nationalism?” American Journal of Student Research 2, no. 4 (2024): 1-17.

- U.S. Congress. Statutes at Large. 18 U.S.C. § 1385 (The Posse Comitatus Act of 1878).

- Wang, et al. “Forcible measures for maritime law enforcement by the coast guard.” Frontiers in Marine Science 12 (2025): 1-13.

- Weeks, William E. The War of 1812: America’s War of Honor. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006.

- Wood, Gordon S. Empire of Liberty: A History of the Early Republic, 1789-1815. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

The Smuggler Who Saved the City: Jean Lafitte at the Battle of New Orleans

The winter of 1814 settled heavily over the swamps and bayous of Louisiana, but the chill that gripped New Orleans was born not of the weather, but of dread. A massive, experienced British invasion force—veterans of the Napoleonic Wars—was sailing toward the vulnerable city. The commander of the American defense, Major General Andrew Jackson, had scraped together a motley crew of regular army troops, militiamen, free men of color, and Choctaw warriors. Yet, he lacked the single most vital component for defense: powder, cannonballs, and men skilled enough to fire them.

This desperate need set the stage for one of the most unlikely alliances in American history, centered on a man whose name was whispered in both fear and awe: Jean Lafitte.

Lafitte was no mere rogue; he was the charismatic leader of a vast privateering and smuggling operation based on the remote island of Grande Terre in Barataria Bay. He held a price on his head, yet his warehouses were overflowing with contraband—and, more importantly, high-quality cannons and a cadre of hardened sailors who knew how to handle them.

The Devil’s Bargain and the Patriot’s Choice

In September 1814, the British made their play. They sent emissaries to Grande Terre offering Lafitte £30,000, a commission in the Royal Navy, and full pardon for his crimes if he would guide their forces through the treacherous bayous and contribute his own guns and men.

Lafitte, ever the pragmatist and the theatrical showman, pretended to consider the offer. But the Baratarian leader had a more complex allegiance than the British assumed. He detested the idea of British rule and saw in the American desperation an opportunity for redemption. Lafitte stall the British and immediately forwarded their plans to the American authorities—including Governor Claiborne, who still held a warrant for Lafitte’s arrest.

When General Jackson finally arrived, he initially dismissed Lafitte as a scoundrel. But the sheer reality of the military crisis soon changed his mind. Jackson’s officers, desperate for resources, convinced him that Lafitte was their only source of the materiel necessary to arm their earthworks. Jackson, known for his iron will and willingness to take risks, accepted the devil’s bargain. He pledged a full pardon to Lafitte and his men if they fought honorably.

The Decisive Contribution

Lafitte delivered immediately and without hesitation. He emptied his stores, providing the American artillery corps with thousands of pounds of gunpowder, cannon shot, and crucial flints for muskets.

More vital than the supplies were the men. Lafitte’s Baratarians were not soldiers, but as smugglers and privateers, they were expert gunners—precise, calm under fire, and intimately familiar with the black-powder trade. Two of Lafitte’s chief lieutenants, the brothers Dominique You and Renato Beluche, took command of batteries 3 and 7, positioned at key points along Jackson’s defensive line, known as “Line Jackson.”

The Bloody Fog of January 8th

On the morning of January 8, 1815, the British launched their frontal assault against the prepared American lines. The battlefield was shrouded in a heavy fog that soon lifted to reveal thousands of British Redcoats marching in tight formation across the open cane fields.

It was then that the Lafitte men, stationed behind their dirt and cotton bale ramparts, unleashed hell. Under the command of You and Beluche, the Baratarian batteries fired with a speed and accuracy that stunned the British. The privateers knew how to load and cycle their weapons with murderous efficiency, tearing devastating holes through the advancing enemy ranks. Dominique You, in particular, operated his battery with the furious precision of a master craftsman, turning the artillery into a deadly, sustained force.

The British formations were shredded before they could even reach the American lines. Within a devastating hour, the battle was a decisive American victory, marked by staggeringly lopsided casualties—over 2,000 British dead or wounded versus fewer than 75 American.

Jean Lafitte and his Baratarians had held their end of the bargain. Their expertise in gunnery and their crucial contribution of resources transformed Jackson’s tenuous defense into an impregnable fortress. True to his word, Andrew Jackson ensured that Lafitte and his men received a full pardon from President Madison, erasing the blot of their past crimes and securing their legendary place in the history of the Republic. The pirate, by choosing patriotism over profit, had saved the city that had once hunted him.

You must be logged in to post a comment.