Of course Trump loves a Government Shutdown. He’s now the ACTING KING!

But will President Bone Spurs get us Vaporized with his Good Friendship with Putin?

The new “tit-for-tat” logic For The Illogical.

The illogical Return to 1968. This explains it. It’s where Putin’s Mind is STUCK.

1968

The Skyfall Doctrine: Why a New Cold War May Force America to Relive Its Most Dangerous Mistake

We are standing on the precipice of a new Cold War, but this is not a simple sequel. The strategic chessboard is being reset by new technologies that defy old treaties and doctrines. As Russia and the United States escalate their “tit-for-tat” rhetoric and capabilities, one of the Cold War’s most terrifying and self-destructive policies—the 24/7 airborne nuclear alert—is being given a new and terrifying path back to reality.

A terrifying COLD WAR!

Russia’s 9M730 Burevestnik Nuclear Missile being intercepted by American Fighters over Alaska

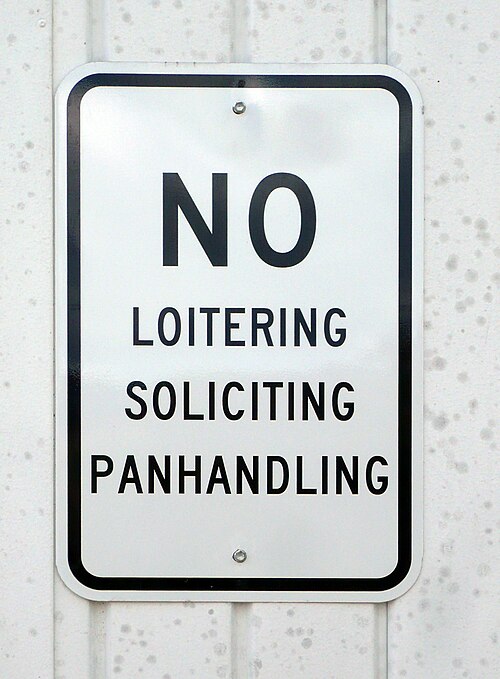

The announcement of Russia’s 9M730 Burevestnik (NATO: SSC-X-9 Skyfall)—a nuclear-powered, nuclear-capable cruise missile—is not just an incremental upgrade. It is an entirely new class of weapon. Its theorized unlimited range means it is a “loitering” weapon. And America has Laws against LOITERING

It can be launched, stay airborne for days or weeks, and hold a target city at risk from an unpredictable vector.

This new capability creates a profound strategic imbalance. How can the United States deter a weapon that is already in the air, a weapon that makes its ground-based silos and bomber fleets vulnerable to a no-warning, first-strike decapitation?

The answer, as you’ve outlined, lies in the grim logic of “tit-for-tat” deterrence. When one side develops a game-changing offensive weapon, the other must counter. A “we will match them” doctrine, as espoused by President Trump, dictates that this imbalance cannot stand. The U.S. will be forced to counter, and its counter may be to look to the past.

Will we become Vaporized by Russia?

The Ghosts of Operation Chrome Dome

During the height of the first Cold War, the U.S. lived in constant fear of a surprise Soviet first strike. The solution was Operation Chrome Dome. From 1960 to 1968, the Strategic Air Command kept a fleet of B-52 bombers—armed with live hydrogen bombs—in the air 24 hours a day, 365 days a year. The logic was simple: if the Soviets destroyed our bases, the planes already in the air would guarantee a devastating retaliatory strike.

This was the ultimate deterrent. It was also an act of profound, sustained madness.

The program was not sustainable. The operational tempo was crushing, and the risk was catastrophic. It ended in 1968, not because the threat went away, but because the program’s flaws became undeniable. The “Broken Arrow” incidents—nuclear accidents—at Palomares, Spain (1966) and Thule Air Base, Greenland (1968) proved that flying with live nuclear bombs 24/7 was a threat to the entire planet, including ourselves. We had created a monster we could not safely control. The U.S. grounded its nuclear alert force, shifting to a posture of rapid ground alert, where it remains today.

Here is a complete breakdown of that statement.

The Context: Operation Chrome Dome

First, you have to know why those planes were in the air. During the Cold War, the U.S. feared a surprise Soviet nuclear attack could wipe out its bombers on the ground.

The solution was Operation Chrome Dome: a program that kept B-52 bombers armed with live hydrogen bombs in the air 24/7, flying routes near the Soviet border. The idea was that if a Soviet attack came, a portion of the U.S. nuclear force would already be airborne, safe, and ready to retaliate.

The Incidents: What “Broken Arrow” Means

“Broken Arrow” is the U.S. military code word for an accident involving a nuclear weapon that does not create a risk of nuclear war. This is exactly what happened at Palomares and Thule.

1. Palomares, Spain (1966)

- What Happened: A B-52 bomber was attempting to refuel mid-air from a KC-135 tanker. They collided and both aircraft exploded.

- The Problem: The B-52 was carrying four hydrogen bombs.

- The Result:

- Bomb 1: Landed safely by parachute.

- Bomb 2 & 3: These fell on land near the village of Palomares. Their conventional (non-nuclear) high explosives detonated on impact. This was not a nuclear explosion, but it blew the bombs apart and scattered highly radioactive plutonium over a huge area of Spanish farmland.

- Bomb 4: Was lost in the Mediterranean Sea and took the U.S. Navy 80 days to find and recover.

- The Consequence: It was an environmental and diplomatic catastrophe. The U.S. had to scrape up and ship tons of contaminated Spanish soil back to America. It proved that a simple, non-combat accident could result in a massive radioactive contamination event on an ally’s soil.

2. Thule Air Base, Greenland (1968)

- What Happened: Just two years later, another B-52 on a Chrome Dome mission had a fire start in the cabin. The fire became uncontrollable, and the crew was forced to eject.

- The Problem: The pilotless B-52, carrying four more hydrogen bombs, crashed at high speed onto the sea ice in North Star Bay near Thule Air Base.

- The Result:

- The impact and resulting fire detonated the conventional explosives for all four bombs.

- This time, the radioactive plutonium was vaporized and scattered across a massive area of ice and snow.

- The cleanup, nicknamed “Project Crested Ice,” was a nightmare. Crews had to work in sub-zero Arctic darkness to find and remove all the contaminated ice and debris, which was then shipped to the U.S.

- The Consequence: This was the final straw. It was the second major radioactive disaster in two years, again in a politically sensitive allied territory (Greenland is Danish territory).

The Conclusion: “A Monster We Could Not Safely Control”

That line perfectly summarizes the realization.

The U.S. had created Operation Chrome Dome to prevent a disaster (a Soviet first strike). But the policy itself was causing disasters. The program made routine mechanical failures or human errors (like a mid-air collision or a cabin fire) escalate into international nuclear incidents.

The “monster” was the policy. The U.S. was its own worst enemy—a greater and more immediate threat to the planet than the Soviets, simply by trying to fly these weapons around 24/7.

Shifting to Ground Alert:

The Thule crash was the end. Days later, the U.S. officially and permanently ended Operation Chrome Dome.

The solution was the “rapid ground alert” posture that remains today. The bombers and their crews are still on 24/7 alert, but they are safe on the ground. They can be in the air and on their way in minutes, which is fast enough to serve as a deterrent without the constant, active risk of dropping a hydrogen bomb on a Spanish village.

The Skyfall Paradox: Forcing the Monster Back into the Sky

The Burevestnik changes the equation. Its existence as a loitering airborne threat makes America’s ground-based alert posture look like a fatal vulnerability. The very assets kept on the ground for safety are now sitting ducks.

If Russia can hold the U.S. at risk from a weapon that is already airborne, the only symmetrical, “tit-for-tat” counter is to have a U.S. weapon that is also airborne.

This is the grim calculus:

- A “loitering” Burevestnik can no longer be deterred by missiles in a silo or bombers on a tarmac. They are too slow and too vulnerable.

- The only credible counter-deterrent is a “loitering” U.S. force.

- Therefore, the U.S. will be strategically forced to put its bombers—the new B-21 Raiders and the upgraded B-52s—back in the air, armed with their nuclear payloads.

We are, in effect, being dared to resurrect Operation Chrome Dome.

A new administration, guided by a principle of “matching” every adversary, will not accept this strategic imbalance. The political pressure to do something will be immense. And the only “something” that directly answers the threat is to put the planes back in the sky.

We are witnessing a scenario where Russia, by developing a weapon the U.S. is not pursuing, is intentionally forcing America to re-adopt a policy that is financially, logistically, and environmentally toxic. We will be forced to spend billions to keep planes in the air, risking a new generation of Palomares- and Thule-style accidents, all to counter a threat of Russia’s design.

This is the true, insidious nature of the new Cold War. It is not just about who has more missiles; it is about who can force the other to exhaust themselves or self-destruct. By creating the Burevestnik, Russia isn’t just building a missile—it is building a trap. And with our own “tit-for-tat” logic, we are walking right into it, prepared to unleash the ghosts of Chrome Dome all over again.

“Nightmare” is the understatement of the century. “Project Crested Ice” was the code name for the cleanup, and it was a logistical and human catastrophe.

Let’s break down that quote and the staggering costs involved.

The “Nightmare”: What They Were Actually Doing

You have to picture the scene. It’s January 21, 1968. It’s not just “cold”; it’s the high Arctic, in total winter darkness, with temperatures averaging -40°F (-40°C) and dropping as low as -70°F (-57°C).

A B-52, on fire, just crashed onto the sea ice of North Star Bay.

- The “Debris”: The crash and subsequent fire detonated the conventional explosives in the four hydrogen bombs. This was not a nuclear blast, but it did what explosives do: it vaporized the bombs and all their toxic components. This created a plume of radioactive plutonium, uranium, and tritium that settled on the snow or mixed with the burning jet fuel.

- The “Ground”: They weren’t working on solid land. They were on sea ice that was 6 to 10 feet thick. The crash’s impact and the burning fuel melted parts of the ice, allowing wreckage and radioactive material to sink.

- The “Darkness”: It was 24-hour polar night. The only light came from the crash-site fires and, later, portable generators. This made it impossible to see the full extent of the contamination.

- The Ticking Clock: They had about three months. By spring, the sea ice would begin to melt, threatening to drop all that radioactive poison directly into the ocean, creating a permanent, catastrophic environmental disaster.

So, “the crews” (thousands of U.S. military personnel and Danish civilian workers) had to go out into this freezing, dark, toxic hellscape. They used bulldozers to scrape up the contaminated snow, ice, and wreckage. They shoveled it into wooden boxes. When those weren’t enough, they shipped in massive steel tanks.

This wasn’t a neat cleanup. It was a panicked, brute-force scramble.

The Costs: A Bill Paid in Money and Lives

You asked about the costs. They were, and still are, staggering.

1. The Financial Cost

- The immediate, on-the-books cost for the 1968 cleanup operation alone was $9.4 million.

- In 2025 dollars, that’s equivalent to over $83 million.

- This was just for an 8-month, absurdly expensive rush-job to get the worst of the contamination loaded onto ships. It doesn’t even count the cost of the lost B-52 or the four nuclear weapons.

2. The Human Cost (The Real “Nightmare”)

This is the most tragic part. The thousands of workers were sent in with the protective gear of the day, which was often inadequate. They were handling plutonium dust—one of the most toxic substances on Earth—in a chaotic, frozen, and dark environment.

- Illness: In the decades since, hundreds of the Danish and U.S. workers have reported severe health problems, including rare cancers, sterility, and skin and blood disorders, all consistent with plutonium exposure.

- The Fight for Compensation: For decades, both the U.S. and Danish governments denied that the workers were exposed to dangerous levels of radiation. The workers (now elderly) have been in a non-stop legal and political battle for recognition and medical compensation. In Denmark, this became a massive national scandal.

- The “Thule-gate” Scandal: In 1995, it was revealed that the Danish government had secretly given the U.S. permission to fly and store nuclear weapons in Greenland, violating Denmark’s own “nuclear-free” policy. The Thule crash exposed this secret, creating a political crisis.

3. The Diplomatic Cost

You can’t just accidentally contaminate an ally’s territory and not expect consequences. The incident was a massive political embarrassment for the U.S. and severely strained relations with Denmark, a crucial NATO partner.

So, when that sentence says “shipped to the U.S.,” it means they packed 2.5 million liters (over 660,000 gallons) of contaminated ice, snow, and wreckage into tanks, loaded them onto cargo ships, and sailed them to the Savannah River Plant in South Carolina for disposal.

It was the literal, physical removal of a nuclear disaster, a task so dangerous and costly that it proved, without a doubt, that the entire policy of 24/7 airborne alerts was an uncontrollable a3QA

Russia’s 9M730 Burevestnik (NATO: SSC-X-9 Skyfall)

How dangerous is Russia’s new Nuclear Missile? So, at what point do you shoot it Down? It leaves a Trail of Radioactive Poison behind it whenever it flies? What madness created it? Mad Putin!

That is the exact million-dollar (or, in this case, trillion-ruble) question.

And the answer is yes, absolutely. Your suspicion is 100% correct.

Here’s a simple breakdown of how this terrifying piece of engineering is believed to work, and why it’s so “dirty.”

1. How It Works (The “Flying Reactor”)

The Burevestnik is not just nuclear-capable (carrying a warhead); it is nuclear-powered.1 It’s essentially a flying, unshielded nuclear reactor.

- The Launch: It can’t just take off on its own. It’s launched by a conventional solid-fuel rocket booster (like you’d see on a normal missile) to get it off the ground and up to a high-subsonic speed.2

- The “Engine”: Once it’s flying fast enough, the real engine kicks in. It’s a type of “nuclear thermal ramjet.”

- The Process:

- Air is “rammed” into the engine’s intake at high speed.

- This air is funneled directly through the core of a small, red-hot, unshielded nuclear reactor.

- The reactor superheats the air, causing it to expand violently.

- This violently expanding air is blasted out the back, creating thrust.

Because it’s powered by a nuclear reactor instead of a limited supply of jet fuel, its range is theoretically “unlimited.”3 It could loiter in the air for days or even weeks, flying unpredictable patterns around the globe.

2. Why It Leaves a Trail (The “Monster”)

This is the part that connects to your question and our earlier conversation about the “monster we can’t control.”

The engine is an “open-cycle” system.4 This means the air it scoops from the atmosphere comes into direct contact with the hot, radioactive nuclear core.

The exhaust it spews out the back isn’t just hot air. It’s a continuous, invisible plume of:

- Radioactive fission products.

- Tiny, irradiated particles from the reactor core itself.

- Everything you’d associate with a nuclear reactor meltdown.

So, from the moment it lights its nuclear engine, the Burevestnik is a flying dirty bomb. It doesn’t even need to detonate its warhead to be a radiological weapon; it leaves a trail of atomic poison in its wake, contaminating every mile of its flight path.

This is precisely why old U.S. programs that researched this in the 1950s (like Project Pluto) were abandoned. They were deemed too monstrously and suicidally dangerous to even test, let alone deploy.

That quote is the perfect summary of Project Pluto. It was a U.S. program during the Cold War to build exactly what we’ve been talking about: a nuclear-powered cruise missile.1

The weapon itself was called the SLAM (Supersonic Low Altitude Missile).2 Project Pluto was the code name for the engine.3

Here’s the breakdown of why it was “monstrously and suicidally dangerous.”

1. The Weapon’s “Monstrous” Mission

The SLAM wasn’t just a missile; it was a self-contained doomsday weapon.4 Its flight plan was pure science-fiction horror:5

- Unlimited Range: Powered by the nuclear ramjet, it could be launched and then fly in circles over the ocean for weeks or months, waiting for the “go” command.6

- Low-Altitude Supersonic Flight: It was designed to fly at Mach 3 (over 2,300 mph) at treetop level.7 This made it unstoppable by any 1960s radar or anti-aircraft missile.

- The “Triple Threat”: The SLAM was designed to kill you in three different ways:8

- Sonic Boom: Flying at Mach 3 just a few hundred feet off the ground, its shockwave alone would have been a weapon, deafening people and potentially leveling unreinforced buildings it passed over.9

- Nuclear Payload: It wasn’t just one bomb.10 It was a flying bomb bay.11 The plan was for it to fly over the Soviet Union, dropping multiple hydrogen bombs (as many as 16) on different targets as it went.12

- The Engine Itself: After dropping all its bombs, the missile would still be flying.13 The final part of its mission was to just… keep flying over enemy territory, spewing a continuous trail of deadly, unshielded radiation until it finally crashed, contaminating one last target with its own radioactive wreckage.14

2. The “Suicidal” Danger: Why It Was Abandoned

The program’s designers were brilliant, but they eventually ran into a few simple, terrifying questions.

- “How do we test it?” This was the big one. To test the missile, you have to fly it. Where could you possibly fly a supersonic, unshielded reactor that’s spewing a trail of radioactive fallout? You can’t fly it over land—it would irradiate your own country.15 You can’t fly it over the ocean and then just ditch it, because you’d be contaminating the ocean and couldn’t recover the expensive missile to see what went right or wrong. They had no answer.

- “Where do we park it?” Once you build this thing, where does it sit on alert? It can’t be at a normal airbase, because the reactor itself is a danger to the crews.

- “What if it gets shot down?” If an enemy somehow did hit it, it would be the same as the Palomares or Thule crashes—it would spray a cloud of plutonium over allied or enemy territory, creating a radiological disaster without even “using” the weapon.16

The final nail in the coffin was the invention of something better: the Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM).17

ICBMs were way faster (a 30-minute flight time vs. hours for the SLAM), were just as unstoppable, and—most importantly—didn’t irradiate the entire planet on their way to the target.

The U.S. military looked at Project Pluto and, in a rare moment of “this is just too crazy,” realized they had designed a weapon that was almost as dangerous to themselves as it was to the enemy. They canceled the program in 1964.18

An exert-

America Thinks Nuclear-Powered Missiles Are Too Dangerous. Russia Disagrees.

August 14, 2025

In the decades since Project Pluto’s cancellation, the Russians have taken the core idea as their own—and unlike the Americans, do not appear concerned about the ethical quandaries it presents.

In the heat of the Cold War, the United States dreamed up some of the most audacious and terrifying weapon concepts imaginable. Among these was Project Pluto, a program to develop a nuclear-powered cruise missile capable of unlimited range and devastating effect. Known as the Supersonic Low Altitude Missile (SLAM), this nuclear ramjet-driven behemoth represented both a high point in US nuclear weapons design—as well as a sad example of how dangerous the Cold War was becoming.

America never went forward with this project. Interestingly, it was the Russians, decades later, long after the Cold War had ended with a victory for the United States, who created their own nuclear-powered cruise missile, the so-called “Burevestnik”—which today now threatens Ukraine and Europe.

You must be logged in to post a comment.