Here is a tale of the real hidden history of Coryell County, it’s brave folks, and Billy the Kid written for the young and the brave. These tales are passed along at Christmas Time from generation to the next generation who learned History Talk always lived longest when told in person.

The Saint of the Cedar Brakes

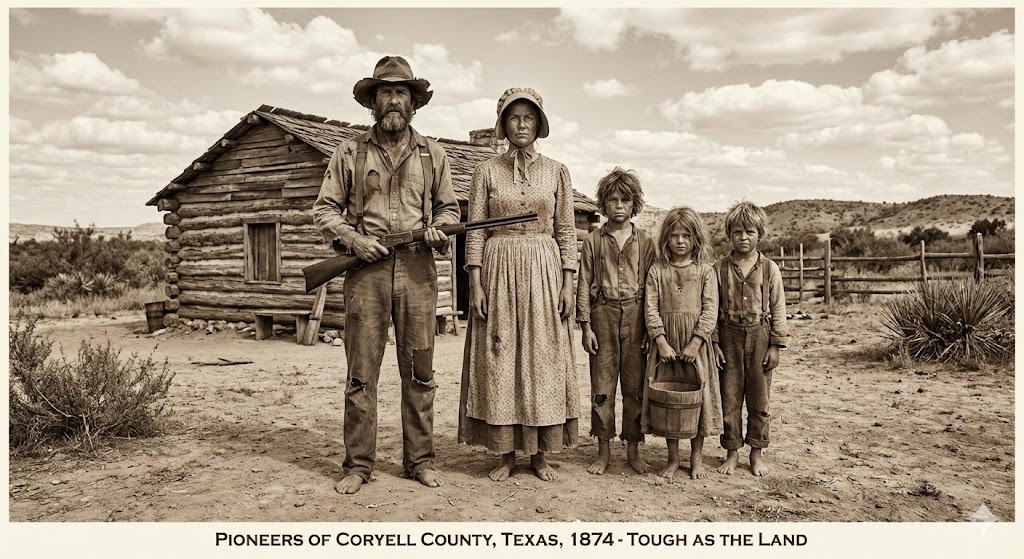

To the fancy folks in Austin or the bankers back East, the hills of Coryell County were nothing but rock, cedar, and dust. They looked at the families living in the hollows—barefoot children with calloused soles and mothers washing clothes in the creek—and saw only poverty. They called them “wild as animals.” But maybe the meanest, bravest of us all Americans.

But the folks of Coryell knew better. They knew they were royalty in rags. A breed unto themselves.

They were the sons and daughters of Giles County, Tennessee. A super-tough breed of American who had walked through hell and high water to stake a claim on the Texas soil. They were “Lord Believers” with bibles in their left hands and rifles in their right. They didn’t have much coin, but they had a code: You treat a neighbor like kin, and you treat the Law like a rattlesnake—with extreme caution.

It was into this sanctuary of stone and spirit that the Old Man came.

He didn’t look like a demon, as the newspapers claimed. He came riding a ragged mule, whistling a tune that sounded like a lonesome wind. He called himself “Roberts,” but the old-timers, the ones who remembered the range wars, noticed two things immediately: his hands were small and quick as lightning, and his eyes were a piercing, laughing blue.

To the outside world, Billy the Kid was dead—buried in New Mexico since 1881. But to the barefoot boys of Coryell, he was the secret king of the backcountry.

Young Jemmy, a boy of twelve with dust in his hair and adventure in his heart, was the first to spot the pistol tucked under the Old Man’s coat. It wasn’t a shiny toy; it was a tool, worn smooth by time.

“Are you him?” Jemmy asked one sweltering afternoon, sitting on the porch of a cabin built on land that felt permanent, though the government would one day steal it away to build the great beast known as Fort Hood.

The Old Man just winked, carving a whistle out of a peach pit. “I’m just a man who prefers the company of honest poor folks to the lies of a rich lawman.”

And that was the truth of it. The Texas Rangers, with their silver stars and cold eyes, rode through Coryell looking down their noses at the Tennessee transplants. They saw dirt. The Old Man saw dignity.

When the winter blew hard and the crops failed, it wasn’t the Rangers who dropped a sack of flour on the widow Miller’s porch. It was the Old Man. When the tax collectors came threatening to seize the hard-won acres of a Confederate veteran’s family, it was the Old Man who sat quietly cleaning his Winchester on the fence line, his mere presence turning the greedy men back toward the city.

He found peace among the “wild” people. He loved them because they were fierce. They didn’t care about the price on a man’s head; they cared about the price of his soul. And they saw that his soul was good, even if his history was bloody.

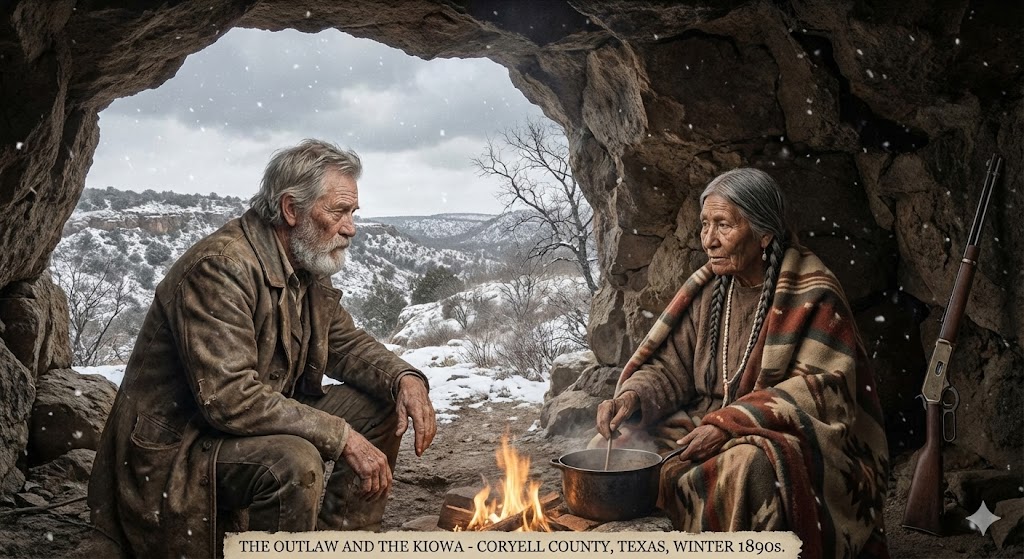

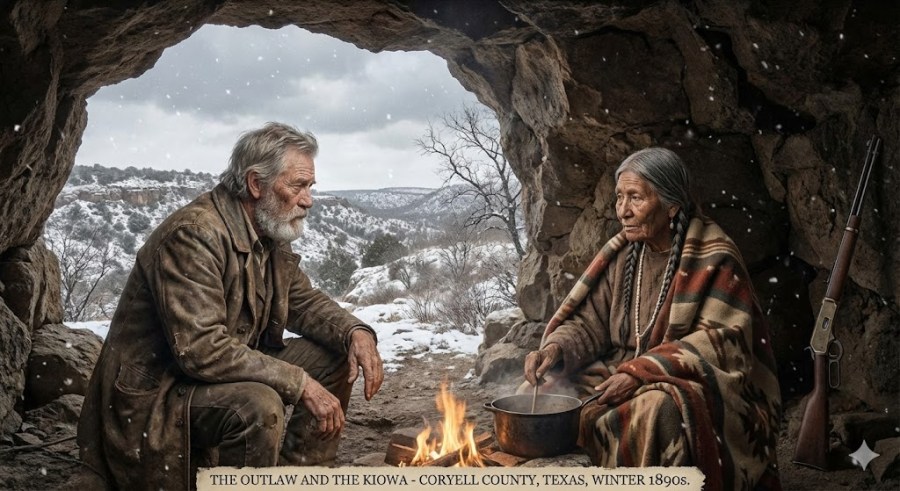

Billy lived the freezing winters in a Cave along the CowHouse Creek with an old Squaw of the Kiowa Nation. Everyone knew who he was and where to find him, but he was just being human and fed, as anyone, on his needs.

“Why do you stay here, Mr. Roberts?” Jemmy asked him once, looking out over the rolling hills that turned purple in the twilight. “You could go to Mexico. You could be rich.”

The Old Man looked at the boy, then at the rugged families gathering for a prayer meeting under the brush arbor, their voices rising in a hymn that shook the leaves of the pecan trees.

“Son,” the Old Man said, his voice raspy but warm, “I’ve ridden a thousand miles and seen a thousand towns. But there ain’t no fortress stronger than a friendship forged in Coryell County. The world thinks I’m a ghost. Let ’em think it. A ghost can’t be hanged, and a ghost can watch over his own.”

Years later, when the government men finally came with their papers to take the land for the Army base, driving the Giles County breed off the soil they had bled for, some say the Old Man was already gone.

But the young ones, the dreamers like Jemmy who grew up to tell the tale, knew better. They knew that somewhere deep in the cedar brakes, where the air smells of rain and freedom, the Kid was still riding. He remained the guardian of the poor, the friend of the barefoot, and the eternal enemy of the pompous.

He was Billy of the Hills, and in the hearts of Coryell, he never died.

You must be logged in to post a comment.