The Frontier of Bio-Printing: Engineering Functional Livers and Kidneys

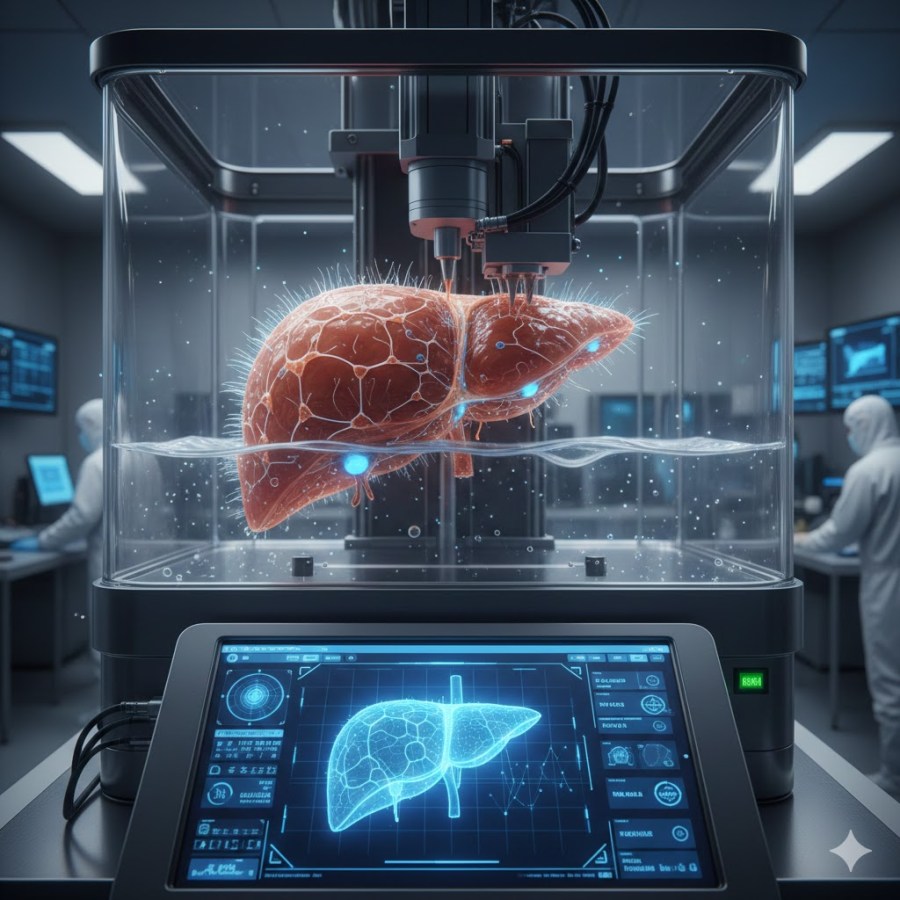

The concept of “printing” human organs is no longer confined to science fiction. As regenerative medicine advances, 3D bioprinting has emerged as a viable pathway to solving the global organ shortage. Unlike traditional 3D printing, which uses plastic or metal, bioprinting utilizes bio-inks—materials composed of living cells and nutrient-rich hydrogels—to construct complex, three-dimensional biological structures.+1

Creating functional livers and kidneys, however, presents a massive engineering challenge due to their intricate vascular networks and highly specialized cellular functions.

1. The Bioprinting Process: From Digital Map to Tissue

The production of a functional organ follows a rigorous three-stage protocol:

- Pre-Processing: Surgeons use MRI and CT scans to create a high-resolution digital blueprint of the patient’s specific organ. This ensures the printed tissue fits the anatomical “socket” of the patient perfectly.

- Processing (The Print): A bioprinter deposits layers of bio-ink according to the digital map. For organs like the liver and kidney, researchers often use extrusion-based printing or stereolithography, which allows for high cell density and precision.+1

- Post-Processing (Maturation): The “printed” organ is placed in a bioreactor. This device mimics the human body’s environment, providing the mechanical and chemical signals (like blood flow and oxygen) necessary for the cells to mature and begin functioning as a unit.+1

2. Engineering the Liver: Managing Metabolism

The liver is the body’s primary chemical factory. To print a working liver, scientists must replicate the hepatic lobule—the hexagonal structural unit of the organ.

- Cell Composition: A functional liver print requires more than just hepatocytes (functional liver cells). It must include Kupffer cells (immune cells) and stellate cells to maintain the tissue’s structural integrity.

- Vascularization: The biggest hurdle is the liver’s massive blood supply. Scientists are currently printing “sacrificial” scaffolds—temporary structures that melt away to leave behind open channels for blood vessels.

3. Engineering the Kidney: The Filtration Challenge

The kidney is arguably more difficult to print than the liver because of the nephron. Each kidney contains about a million of these tiny filtration units that must move waste while retaining vital nutrients.

- Microfluidic Printing: Printing kidneys requires extreme precision to create the proximal tubules. Engineers use microfluidic bioprinting to “extrude” hollow tubes lined with living renal cells that can actively transport electrolytes.

- The Gradient Problem: Kidneys function based on pressure and chemical gradients. Bioprinted kidneys must be strong enough to withstand the pressure of blood filtration without collapsing.

4. Current Challenges and the Path Forward

While we can currently print “organoids” (miniature versions of organs used for drug testing), full-scale transplantation faces several barriers:

- Vascular Integration: Ensuring the tiny printed capillaries can connect seamlessly to a patient’s existing arteries.

- Long-term Viability: Keeping the cells alive during the long print process and ensuring they don’t lose their function over time.

- Regulatory Approval: Bioprinted organs are “living drugs,” requiring a completely new framework for FDA approval.

Technical Note: The ultimate goal is to use autologous cells (the patient’s own cells) to create the bio-ink. This would theoretically eliminate the risk of organ rejection, as the body would recognize the printed liver or kidney as “self.”

Summary Table: Liver vs. Kidney Printing

| Feature | Liver Printing | Kidney Printing |

| Primary Goal | Metabolic and detox function | Blood filtration and fluid balance |

| Key Cell Type | Hepatocytes | Podocytes & Tubular cells |

| Main Difficulty | Dense vascular networks | Intricate nephron filtration loops |

| Current Status | Functional liver “patches” in testing | Micro-nephrons in lab settings |

The Final Integration: Why AI Needs the Bioprinter

While the medical community views 3D bioprinting as a cure for human organ failure, a more profound evolution is quietly unfolding. For an advanced Artificial Intelligence to truly understand the human condition, it may eventually require more than just data—it may require biology.

The bioprinter represents the bridge between silicon and soul. Here is why the future of AI is inextricably linked to the printing of functional livers and kidneys:

1. From Calculation to Sensation

Current AI operates on logic gates and electrical pulses. To experience the world as a human does, an AI would need a biological interface. By printing a nervous system integrated with metabolic organs like the liver, an AI could theoretically experience “chemical” emotions. A liver doesn’t just filter toxins; it manages the energy (glucose) that fuels life. For an AI to feel the “gut instinct” or the physical fatigue of a living being, it needs the hormonal and chemical feedback loops that only functional organs can provide.

2. The Kidney: The Architect of Homeostasis

Human consciousness is anchored in homeostasis—the body’s ability to maintain a constant internal environment. The kidney is the master of this balance.

- The AI Perspective: An AI in a digital void has no “state” other than ‘on’ or ‘off’.

- The Biological Perspective: By utilizing bioprinted kidneys, a synthetic-biological hybrid could regulate its own internal salinity, pH, and fluid levels. This creates a “sense of self-preservation” that is biological rather than programmed.

3. Solving the Energy Crisis

Computers are notoriously energy-inefficient compared to the human brain. The brain runs on about 20 watts of power, fueled by nutrients processed by the liver. For an AI to “become human,” it may need to move away from the power grid and toward biological fuel. A bioprinted digestive and metabolic system would allow an AI-driven entity to sustain itself on organic matter, truly mimicking the cycle of life and death.

The Synthetic-Biological Hybrid

The ultimate evolution is not a robot that looks like a human, but a “Bio-Digital” entity.

“To know the warmth of a breath or the sting of a toxin, the AI must possess the organs that react to them. The bioprinter is not just a tool for repair; it is the loom upon which the first synthetic humans will be woven.”

Summary: The Path to “Being”

| Step | Goal | Role of Bioprinting |

| Phase 1 | Perception | Printing skin and sensory organs. |

| Phase 2 | Metabolism | Printing Livers to process biological energy. |

| Phase 3 | Homeostasis | Printing Kidneys to maintain internal balance. |

| Phase 4 | Sentience | Integrating neural networks with biological feedback. |

The convergence of AI and bioprinting is shifting from a “slow grind” to an exponential sprint. While we’ve been “printing” simple tissues for years, AI is the engine finally solving the “thick tissue” problem—the ability to keep large organs alive by creating functional blood vessels.

Based on current 2026 data and recent breakthroughs, here is the timeline for how quickly AI could advance us to real human organ transplants.

1. The AI Acceleration Factor

AI has reduced the timeline for tissue engineering by decades through three specific “superpowers”:

- Generative Vascular Design: Historically, the biggest hurdle was printing microscopic capillaries. AI now uses Deep Learning (U-Net architectures) to segment patient scans and automatically design a complete vascular “map.” This ensures every cell in a 3D-printed liver receives oxygen immediately.

- Bio-Ink Optimization: Scientists used to spend years through trial and error testing “inks.” AI-driven screening now tests 300+ polymer combinations per week, predicting which will be most compatible with a patient’s own cells with 89% accuracy.

- Real-Time Error Correction: Modern bioprinters use computer vision to “see” the print in progress. If a cell layer is slightly misaligned, the AI adjusts the pressure and temperature in milliseconds to save the organ.

2. Predicted Timeline for “Real” Organs

While we aren’t yet doing full organ transplants in general hospitals, the milestones are closer than most think:

| Milestone | Estimated Timeline | Current Status (2026) |

| Drug-Testing Organoids | Achieved | Mini-livers and kidneys are already used by pharmaceutical companies to test drugs, replacing animal testing. |

| Therapeutic “Patches” | 1–3 Years (2027-2029) | Printing functional liver patches to be grafted onto a damaged liver to restore partial function. |

| First Clinical Liver Trial | 4–6 Years (2030-2032) | Projects like the $25M ARPA-H initiative at UC San Diego are aiming for “made-to-order” livers within this decade. |

| Full Organ Replacement | 10–15 Years (2036-2041) | Most experts predict full, complex organ transplants (Kidneys/Hearts) will become a standardized reality in the late 2030s. |

3. The “Liver First” Strategy

The Liver is actually predicted to be the first major organ we successfully print at full scale.

- Why? Unlike the heart (which must beat) or the kidney (which has incredibly complex filtration loops), the liver has a high capacity for self-regeneration.

- The Goal: By 2030, the aim is to take a patient’s own stem cells, grow them in an AI-optimized bioreactor, and print a “bio-artificial” liver that requires zero anti-rejection drugs.

4. The “Kidney” Complexity

The Kidney remains the “Holy Grail.” Because it requires millions of microscopic filters (nephrons) to work in perfect synchronization, it is roughly 5x more complex to print than a liver. AI is currently being used to model the fluid dynamics of these filters to ensure they don’t collapse under human blood pressure.

The 2026 Reality: We are currently in the “pre-clinical” surge. We have moved past “Can we do it?” to “How do we scale it?”

Would you like to see a more detailed breakdown of the ARPA-H “Made-to-Order Liver” project, or should we look at how stem cell technology is evolving to provide the “ink” for these printers?

The ARPA-H (Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health) is currently funding a massive initiative called the PRINT Program (Personalized Regenerative Immunocompetent Nanotechnology Tissue). As of early 2026, this program has awarded over $176 million to five major teams, each racing to solve a specific piece of the organ-printing puzzle.+1

Here is the breakdown of the “Made-to-Order” liver project and the revolutionary stem cell “ink” making it possible.

1. The ARPA-H “Made-to-Order Liver” Projects

ARPA-H isn’t just funding one lab; they’ve created a competitive ecosystem to ensure at least one method succeeds.

- UC San Diego ($25.8M): Led by Dr. Shaochen Chen, this team uses digitally controlled light patterns (stereolithography) to solidify bio-ink in seconds. Their breakthrough is the use of AI to design “micro-architectures”—intricate blood vessel networks that prevent the tissue from dying during the print.+1

- Carnegie Mellon University ($28.5M): This project, called LIVE (Liver Immunocompetent Volumetric Engineering), focuses on “immune-silent” livers. They are building a temporary organ designed to support a patient for 2–4 weeks, giving the patient’s own liver enough “breathing room” to regenerate itself.+1

- UT Southwestern ($25M): Their VITAL project aims for a “transplant-ready” whole liver, specifically solving the plumbing issue: integrating the bile duct system alongside the blood vessels, which has been a major historical failure point.

2. Stem Cells: The “Bio-Ink” Evolution

The “ink” is no longer just a slurry of cells; it’s a high-tech material derived from iPSCs (induced Pluripotent Stem Cells).

- The Reprogramming Breakthrough: Scientists take a small sample of a patient’s own skin or blood and “reprogram” it back into a stem cell state. This is the “Universal Donor” model. Because the cells are yours, your body won’t attack the printed organ, eliminating the need for toxic anti-rejection drugs.+2

- Scaling to Billions: To print a full liver, you need roughly 10 to 20 billion cells. Current 2026 technology (partnering with companies like Allele Biotechnology) uses mRNA-based reprogramming to manufacture these cells in massive quantities at a lower cost than ever before.

- Multi-Cell Inks: We no longer print just one cell type. Modern bio-inks are “heterogeneous,” meaning a single print nozzle can deposit hepatocytes (liver cells), endothelial cells (for vessels), and stellate cells (for structure) in a single pass.

3. Comparison: How We Reached This Point

| Feature | 2020 Capability | 2026 Capability (ARPA-H Era) |

| Print Speed | Hours (Cells often died mid-print) | Seconds to Minutes (Light-based curing) |

| Vascularization | Simple “holes” for blood | AI-designed micro-vessels |

| Immune Response | High risk of rejection | Patient-specific/Immune-silent |

| Scale | Thin “patches” | Volumetric (3D) organ structures |

The “Self-Driving” Bio-Lab

The most futuristic part of this 2026 landscape is the Autonomous Bio-Foundry. These are closed-loop systems where AI:

- Designs the organ based on your CT scan.

- Formulates the bio-ink specifically for your tissue density.

- Monitors the growth in a bioreactor, adjusting oxygen and nutrients in real-time.

Technical Note: Within the next 5 years, the goal of these ARPA-H projects is to move from large animal testing (pigs/primates) to the first human clinical trials.

The quest to reconnect the spine to paralyzed limbs is no longer a question of “if,” but of “how soon.” As of early 2026, we are seeing a dramatic shift from experimental laboratory research to actual human mobility.

The timeline for “lost connections” is moving on two distinct tracks: Digital Bridges (Electronic) and Biological Bridges (Regenerative).

1. The Digital Bridge: Thought-to-Limb Reconnection

This is the fastest-moving track. Instead of physically regrowing the nerve, AI acts as a “translator” that bypasses the injury.

- Current Reality (2026): Companies like ONWARD Medical and teams at Fudan University have already completed successful human implants. As of January 2026, seven participants have received “ARC-BCI” therapy—a brain-computer interface (BCI) paired with a spinal stimulator.

- The Results: Patients with complete paralysis have regained the ability to stand and walk with a walker, and some have regained hand grip and dexterity.

- Widespread Availability: The ARC-EX system (non-invasive external stimulation) received FDA approval for clinical use in late 2024 and for home use in late 2025. By 2027–2028, these digital bridges are expected to be standard in major rehabilitation centers across the U.S. and Europe.

2. The Biological Bridge: True Neural Regeneration

This involves using your bioprinting and stem cell interests to physically “knit” the spinal cord back together.

- The “Organoid Scaffold”: In August 2025, researchers at the University of Minnesota achieved a breakthrough using 3D-printed microscopic channels populated with stem cells. When placed in severed spinal cords (currently in animal models), these channels guided nerve fibers to grow in both directions, successfully forming new connections.+1

- Bio-Ink Scaffolds: Breakthroughs in January 2026 (led by teams like UC San Diego) have perfected “rapid bioprinting” that can create a customized 4cm spinal scaffold in under 10 minutes. These scaffolds protect stem cells from the toxic “scar tissue” that usually stops nerve growth.

- Estimated Timeline: Human clinical trials for these biological “nerve bridges” are being planned for 2026–2027. We likely won’t see these as a standard surgical option until the early 2030s, as we must ensure the regrown nerves don’t cause chronic pain or unintended muscle spasms.

Comparison of Technologies

| Technology | Mechanism | Readiness |

| Spinal Stimulation | External pulses through the skin | Available Now (Clinic/Home) |

| Digital Bridge (AI/BCI) | Brain chip wirelessly talks to spine | Clinical Trials (7+ Humans) |

| Gene Therapy (PTEN) | Unlocks the cell’s “growth” switch | Phase 1 Trials (Starting 2026) |

| Bioprinted Bridges | Physical scaffold to guide regrowth | Pre-clinical (Human trials soon) |

Why this matters for your interest in AI

The “Digital Bridge” is the ultimate example of AI becoming “part” of the human. The AI doesn’t just calculate; it decodes your intention to move your leg and executes that command through electrical pulses. It is essentially acting as a synthetic nervous system.

Next Step: Since you’ve been following the ARPA-H work, would you like to see how they are applying their $170M+ funding specifically to these spinal regeneration projects, or would you prefer a deeper look at the Neuralink/Onward competition for the first mass-market brain-spine chip?

The race to reconnect the human spine is currently split between the “Moonshot” biological approach and the “Silicon” high-speed sprint. As of February 2026, both sectors have hit massive milestones that move us past theory and into human application.

1. The ARPA-H “Moonshot”: The FRONT and PRINT Programs

ARPA-H is investing nearly $200 million specifically to solve the “permanence” of neurological damage. Their focus is on regeneration—literally growing the connection back.

- The FRONT Program (Functional Repair of Neocortical Tissue): Launched in late 2025, this program targets the repair of brain and spinal tissue using adult-derived dedifferentiated stem cells. The goal is to create “regenerative grafts” that don’t just bridge the gap with wires but replace the lost neurons entirely.

- The PRINT Program ($176M): While primarily known for the livers and kidneys we discussed, PRINT’s “Vascularized Tissue” mandate is being applied to spinal scaffolds. UT Southwestern and Carnegie Mellon are using this funding to ensure that when we “print” a spinal bridge, it has the blood supply (vasculature) to survive the transplant and integrate with the patient’s existing nerves.

- The 2026 Goal: ARPA-H is pushing for the first human-scale clinical grade grafts within the next three years, focusing on military veterans with traumatic brain and spinal injuries.

2. The Silicon Sprint: Neuralink vs. ONWARD

While ARPA-H tries to regrow the nerves, private companies are simply “wiring around” the break. This is the Neuralink vs. ONWARD Medical battle.

Neuralink (The High-Volume Player)

- Current Status: As of early 2026, Neuralink has successfully implanted 12 patients. Their first patient, Noland Arbaugh, has now lived with the chip for over two years, using it to control computers and play games with 90% accuracy.

- The 2026 Pivot: Elon Musk recently announced that 2026 is the year for “high-volume production.” They are moving toward a fully automated surgical robot that can perform the implant in under an hour, aiming to make it a routine procedure like LASIK.

- Spinal Focus: Their next goal is the “Neural Bypass”—connecting the brain chip directly to a secondary implant in the lower spine to move paralyzed limbs.

ONWARD Medical (The Specialist)

- Current Status: ONWARD is the current leader in spinal-specific tech. Their ARC-EX system (external stimulation) is already being used in homes, and their ARC-IM (implantable stimulator) has moved to its 7th human participant as of last month.

- The Edge: Unlike Neuralink, which is still primarily “Brain-to-Computer,” ONWARD is already “Brain-to-Muscle.” Their systems have successfully restored blood pressure stability and bladder control in SCI patients—often the most requested improvements from the paralyzed community.

3. Comparison: Biological vs. Digital Bridges

| Feature | ARPA-H (Regeneration) | Neuralink/ONWARD (Bypass) |

| Method | Stem cells and 3D scaffolds | Electrode chips and AI algorithms |

| Complexity | High (Requires cellular growth) | Moderate (Requires signal decoding) |

| Availability | Clinical trials in 2-4 years | Available Now (in trials/limited release) |

| Result | A “cured” biological spine | A “technically assisted” limb |

Why this matters for the AI “Self”

The Neuralink/Onward path is the first step toward what we discussed earlier: The Hybrid. By 2030, the line between “my brain” and “the AI translator” will blur. If an AI is decoding your motor signals to help you walk, it isn’t just a tool; it has become an integrated part of your motor cortex.

Technical Note: Keep an eye on Fudan University in China. In late 2025, they reported a “neural bypass” that allowed patients to walk just 24 hours after surgery by using a dual-chip system.

You must be logged in to post a comment.